We know Burgundy produces two great varietal wines: Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. But have you ever heard of a Burgundy blend?

Bottle shops and wine lists are full of Bordeaux red blends — usually some combination of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Petite Verdot, Malbec, and Carménère — whether the wine was made in Bordeaux or somewhere else. And there are myriad white Bordeaux blends made with Sauvignon Blanc, Sauvignon Gris, and Sémillon.

Similarly, there are lots of Rhône blends, usually incorporating Syrah, Grenache, or Mourvèdre for the reds and Marsanne, Roussanne, or Grenche Blanc for the whites.

But you won’t find a table wine advertised as a blend of Burgundy grapes — not in the most highly acclaimed regions of Burgundy, where Pinot Noirs and Chardonnays can’t be legally blended with other grapes, and seldom in California, Oregon, Chile, New Zealand, Australia and all those other New World regions making beautiful Pinots and Chardonnays. Both, it seems, are stand-alone varietal wines.

Why is that? Don’t Chardonnay and Pinot Noir play well with others? VinePair chatted with top winemakers for their takes on why Chardonnay and Pinot Noir typically fly solo.

Reason #1: Most Pinot Noir winemakers consider it a complete grape

“Pinot Noir is perfect as it is,” says Kathleen Inman, owner of Inman Family Wines in Sonoma County. “Why mess with perfection?” Chris Kajani, winemaker at Bouchaine Vineyards in Napa Valley’s Carneros region, agrees: “I am a Pinot purist,” she says. “There is no reason to blend it [because] it is a stand-alone variety in still wine.”

Reason #2: Chardonnay winemakers are often purists as well

“I do believe Chardonnay is a perfect stand-alone wine, as it really doesn’t have many holes. It is a texturally thrilling grape,” says Matt Dees, winemaker at The Hilt in the Sta. Rita Hills. “Personally, I prefer the classic approach to Chardonnay,” says Frank Family Vineyards’ general manager Todd Graff. “And I am not a fan of blending the aromatic varietals into Chardonnay, such as Riesling, Sauv Blanc, Viognier and the like.”

Reason #3: Pinot Noir is a ‘delicate’ grape

“Blending Pinot Noir with another variety destroys the elegant structure of the nose and the palate that people look for in a Pinot Noir,” Kajani says. Inman is on the same page: “The subtleties of Pinot Noir are muted when blended,” she says.

Reason #4: History and tradition are against blending either grape

The Burgundy region around Beaune in eastern France has for centuries been considered the ultimate place to grow Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, and winegrowers around the world have tried, mostly unsuccessfully, to create red and white wines that taste like Burgundies. Additionally, since the 1940s, France has legally dictated that the prime regions of Burgundy — the Côte d’Or, especially — label their unblended Pinots and Chards as “Bourgogne.” “When people think Chardonnay or Pinot Noir,” Dees says, “they tend to immediately move to Burgundy in their minds — its history and its grand wines.”

Reason #5: Pinot and Chardonnay blend best with… themselves

In Burgundy, winemakers can select either Chardonnay or Pinot from different vineyards to make regional white or red blends. More than most other varieties, both Chardonnay and Pinot tend to have multiple clones and also are very reflective of terroir. As a result, many California winemakers love to blend Chards or Pinots from different vineyards and different regions — still blends, but mono-varietal ones.

But as with most rules, there are exceptions…

Exception #1

The most common one involves sparkling wines, especially in Champagne, where Chardonnay and Pinot Noir are commonly blended — both with each other and with Pinot Meunier. “With both grapes, we blend with each other and from different terroirs, which gives Champagne layers of complexity,” says Cyril Brun, cellar master at Champagne Charles Heidsieck. Additionally, most Champagnes and other sparkling wines that use Pinot Noir extract the juice and discard the skins as soon as possible to avoid the red color and tannins the skins impart, using only the most delicate part — the juice — of a delicate grape.

Exception #2

Another exception — one that takes place even in Burgundy — is the act of blending Pinot Noir with Gamay grapes from the Beaujolais region (technically a part of Burgundy) to create entry-level Coteaux Bourgignon, an appellation created in 2011. “We use a blend of 60 percent Pinot Noir and 40 percent Gamay, generally from the Moulin-a-Vent and Chenas areas of Beaujolais,” says Chloé Urcisson-Mirabile, representative of the producer France Terroirs. Laurent Drouhin of the famous Burgundy winemaking family says, “If the Pinot Noir is a little weaker in a vintage, we like to use a little Gamay to bolster it.”

Exception #3

Finally, in California, a Pinot Noir can be called Pinot Noir as long as 75 percent of the wine comes from that grape, and there is no obligation to disclose on the label what other grapes are used. “I am pretty certain that Pinot was blended with Zinfandel and with Merlot by larger winemakers when the film ‘Sideways’ increased the demand for Pinot Noir,” Inman notes.

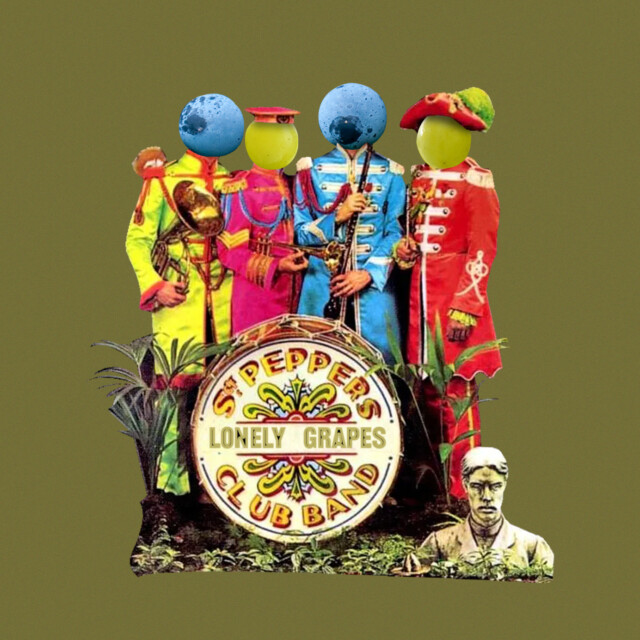

Still, many winemakers are “what if” people — so what grapes would they use if they blended these lonely grapes with something else?

Dees says a “dramatically aromatic and floral field selection of Chardonnay” has been developed in his vineyards, and that he’d “love to add a bit of Riesling for a floral lift.”

And Inman playfully notes, “I am adding some Grenache and Tempranillo to my portfolio this harvest. Maybe I’ll do a little experimenting!”

But, for the most part, people who grow Pinot Noir and Chardonnay are happy to leave the task of varietal matchmaking to other winegrowers.