“It became a whole sh*t show,” recalls Keith Block.

Lines around the block. Police barricades up and down Second Avenue. Giuliani sending his goons around to raid things.

But it had started with a simple idea: What if a bar just let women drink for free?

It was 1990 on Manhattan’s Upper East Side and, after the extravagant 1980s, the neighborhood was in the throes of a countrywide recession and unemployment was on the rise. The 1980s era of Wall Street expense accounts had evaporated as young professionals, for the first time in a while, actually had to pay for their own drinks.

The demographics of the tony Upper East Side were likewise going through some radical changes post-1987’s Black Monday market crash. Normandie Court, a complex of four 34-story beige towers occupying the entire block bounded by East 95th and 96th Streets and Second and Third Avenues, opened around then, offering dirt cheap rent. It was still a sort of wild west that far uptown, and the facility was quickly dubbed “Dormandie” Court for the raucous, college-like atmosphere it had created and then fostered.

Meanwhile, 25 new bars had opened between 76th and 96th Streets in the first years of the 1990s as well. Cramped beer and shot joints with names like the Blue Moon, Czar Bar, and Richter’s were all vying for the attention of this influx of recently graduated young adults who wanted to go out, but had little money to do so.

“The Upper East Side was the place to party in the early 1990s,” recalls Jennifer Capobianco, a bartender from the era. “Bars would battle to get people in the doors.”

Then a bar on First Avenue, Far Out Lounge, came up with a gimmick that would change everything, with the ultimate idea to “draw in the skirts that bring in the suits.”

What if they just let all women drink for free?

Not surprisingly, it worked. And by 1991 a good dozen of the neighborhood’s bars were offering similar ladies’ night deals. Sometimes that meant dispensing a free keg or two of Bud Light until it ran out during a traditional off-night, like Tuesday or Wednesday. Other times, it literally meant all-you-could-drink, whatever you wanted to drink, on every single night of the week.

“Here, women can drink all they want all night long for absolutely nothing,” wrote The New York Times in covering the phenomenon in April of 1991. “They are not obliged to talk to anyone. No one says they have to leave a tip. Since no one’s making them, they don’t.”

Men Are Pigs

Soon there was an all-out war being waged for putting butts on barstools, and in these days before the internet, the bars would advertise their increasingly outrageous specials in the Village Voice and free local fliers sloppily stacked at the entrance to ATM banks, while hoping for write-ups in New York Magazine’s weekly goings-on section.

“Beware salivating yuppie swells there for Ladies Night,” the magazine wrote (fondly) of Manny’s Car Wash, a Chicago-style blues club on East 87th Street.

Many of these bars tried to offer a sort of bridge from cheap college boozing to costly, real-world imbibing. Like Clubhouse on York Avenue, which intentionally offered a frat house-like atmosphere. Spanky’s, a sports bar on 75th Street, attracted the young Republican crowd that had begun to invade the area. There was likewise Brother Jimmy’s, a Southern BBQ joint that served overproof punch out of rubber garbage pails.

Many of the bars of this era were, in fact, themed, and sometimes cheesily so. The Times considered it a “a bit of a fallen Disneyworld,” chalking that up to the era’s young singles having “no pretensions to hipness and a perhaps commendable lack of irony.”

Like Geronimo’s Bamba Bay Cafe (a.k.a. “Mo’s”), a Tex-Mex slash surfer-themed bar with a totemistic statue of Geronimo the Apache Surfer hanging by the entrance and countless big screen TVs. Wednesdays and Thursdays were “Ultimate Ladies Night” with free Margaritas all evening, not to mention a gratis taco bar during happy hour. Harry’s Hula Hut had bamboo walls, palm trees, and Nerf basketball available, plus all-you-can-drink beer. Live Psychic on East 84th offered free drinks and $10 tarot card readings from, yes, live psychics on a platform to the left of the dance floor, while single ladies shimmied to songs like Right Said Fred’s “I’m Too Sexy.” While American Trash, a biker-themed bar, had literal garbage on the walls and ceiling.

Not all these bars were necessarily beloved.

“Basically, we walk in, get our free drinks, give the scum dirty looks and walk out,” a college student named Rebecca said of the Far Out Lounge. While her friend Sara explained, “We don’t even like this place. But we’re not going to complain.”

But some places were so beloved they’re still talked about fondly today.

Like Outback, an Australian-themed bar on 93rd and Third Avenue, which hosted “Men Are Pigs” nights three times a week. Women would crowd around oil drums turned into tables and, while standing on sawdust floors, pound cheap beer and well liquor. Initially, owner Klay Reynolds had allowed ladies to drink whatever they desired; then he went through more Bailey’s Irish Cream in the first month he offered the deal than he would have expected to go through for all of 1991. Still, he found ladies’ night ultimately quite profitable.

“I figure it’s costing me two bucks to put a girl in my bar for two hours,” Reynolds claimed at the time. “That’s pretty good.”

Anarchy on the Upper East Side

I probably don’t need to tell you that bar owners like Reynolds weren’t letting women (or “ladies”) drink for free out of the goodness of their hearts. The crass reason, of course, is because since the beginning of time, straight men have wanted to be drinking in the same place women are drinking because, yes, men are pigs.

The ultimate epitome of this wild, boozing-on-the-cheap era, Ski Bar, was located on Second Ave between 94th and 95th. Block opened it with a partner, Adam Singer, when he was just 22; he had worked at nearby Brother Jimmy’s for just two weeks before getting fired and deciding he could run a better bar. He wasn’t exactly made of money, though — he fished through a bucket of change every morning to buy his one meal of the day, a bagel — but Block claims this was a time when it didn’t cost a ton to open and run a bar in Manhattan. The liquor laws weren’t as strict — Ski Bar didn’t have to have a kitchen nor serve any food — and rent was cheap, both for bar space and the nearby apartments.

“You could be a young person in Manhattan back then,” Block recalls. Indeed, many of his customers would come from Normandie Court a block away. The oppressively hot and always jam-packed Ski Bar was so crazy The New York Times compared its atmosphere to that of a beer commercial, and nightly there were sweaty singles dancing and drinking with unbridled enthusiasm. This was a moment in Manhattan history that had never really been seen before and hasn’t been seen since.

“The all-you-can-drink deals just don’t happen these days, because the rents are so high,” says Block. Ski Bar would issue custom-made lift tickets good for eight drinks apiece. “But those deals enticed 22-year-olds to get out of their apartments. ‘Hey, let’s go get drunk at a bar.’”

Block’s bar was ski-themed, natch, with a Ski-Doo hanging from the ceiling, bartenders wearing neon-colored ski pants in the winter and bathrooms labeled “Unload Here” (men’s) and “Grooming in Process” (women’s). Block says it was the first non-nightclub bar on the Upper East Side to have a DJ booth, in this case a ski lift gondola repurposed from Killington Ski Resort. Despite the lack of a cabaret license, DJ Mike would spin soon-to-be-classics of the moment like Salt-N-Pepa’s “Let’s Talk About Sex” and Color Me Badd’s “I Wanna Sex You Up,” while everyone danced.

Block had learned of high-octane fish bowl cocktails during his brief Brother Jimmy’s stint and Ski Bar served its own versions with names like the Worldcup. Drunk patrons would dance on the bar top, well before Coyote Ugly, which would open in January of 1993, had popularized such shenanigans. Occasionally, a costumed employee they dubbed Jägerman would appear from the back wielding bottles of the potent German digestif in his hands, which he then free-poured into ladies’ mouths as the crowd chanted his theme song: “Jägerman, Jägerman, if you can’t drink it, no one can!”

“It was like feeding baby birds,” recalls Capobianco. “I was always worried about getting a dirty shirt or chipping a tooth.”

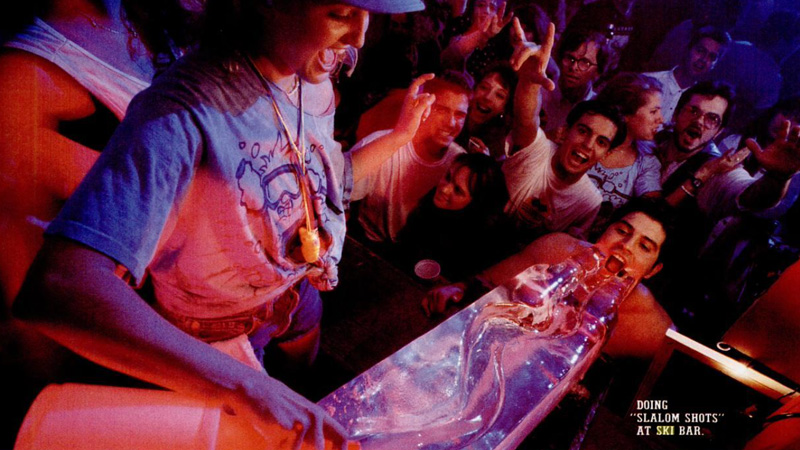

Ski Bar’s biggest attraction was the Slalom Shot, a four-foot-long slab of ice with a twisting trail cut into it. You’d press your lips to the bottom and “Slalom Girls” would pour a combo Jaeger/tequila shot that would shush down the slope and into your face. In the summer of 1992, New York Magazine published a photo of the Slalom Shots alongside a brief blurb and, according to Block, “That more or less started the anarchy in the neighborhood.”

A Brief History of Ladies’ Night Being Illegal

It needs to be said that, technically, ladies’ nights were illegal in New York and had been so for quite a time. In 1972, the New York State Human Rights Commission ruled that reduced-priced ladies’ days at Yankee Stadium discriminated against men. And yet, over the years, bars continued to try to offer ladies’ night deals (whether discounted or completely free drinks) and various factions had tried to stop them.

Like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. “They’re exploiting women by using them to attract men,” claimed its spokeswoman, Daveda Copeland. On the other end of the spectrum, a growing “men’s rights” movement would continue to try and put the kibosh on ladies’ night deals throughout Manhattan and the suburbs, even if their arguments weren’t necessarily made in good faith.

“It is demeaning to women to be treated this way,” claimed Long Island man Richard Savino in 1984. Bar owners argued that they should be able to capitalize on the marketplace however they could and that only the State Liquor Authority could outlaw such ladies’ night deals. And yet, plenty of ladies were also against them.

“I think that free drinks for women is discriminatory and a bad idea,” wrote Cynthia Heimel, a feminist columnist, in the November 1991 issue of Playboy. “The point of ladies’ night is to get women into bars and get them drunk so that men can score.”

Or worse. Even by the early 1990s, the Upper East Side remained haunted by what had happened there in 1986, when the infamous Preppy Killer, Robert Chambers, had pounded tequila and beer chasers at Dorrian’s Red Hand with Jennifer Levin before killing her in Central Park later that evening.

But, most women slugging free beers at Brother Jimmy’s or complimentary Champagne at Jungle Jim’s or on-the-house Slalom Shots at Ski Bar arguably enjoyed these ladies’ night deals. And, of course, so did the men. As Brad Lauren, a 23-year-old production assistant claimed at the time, having just paid $3.50 for a Miller Lite that ladies were drinking gratis: “It’s the most socially acceptable form of discrimination.”

End of the Era

By 1994 lines were down the block at Ski Bar every night and the police started to put up barricades to keep people off Second Avenue. Nearby spots like Bear Bar began capitalizing on the traffic by offering their own competing ladies’ night deals. (And Ski Bar even opened a Ski Bar 2 pop-up at Hunter Mountain during the winter.)

“When we go out drinking, we go for broke,” one man told The Times. “There is no limit to it. It’s until you pass out.”

There were problems, of course; you serve young men and women as much alcohol as they can humanly consume and there’s bound to be. Thankfully, most seemed to only be of the public urination and inconsiderate noise variety, angering wealthy locals. The mayoral election of Rudy Giuliani in 1994 would favor the NIMBYs, as he sent task forces around to raid bars, enforce cabaret laws with hefty fines, and even enact “Operation Last Call,” having police officers carry a meter to check noise levels around closing time.

“That was the start of the end of this era,” says Block. “And why I got out.”

Ski Bar turned into a Taco Bell and Block moved to Telluride, Colo., where he and Singer opened a similar bar, Poachers Pub. He claims the resort-area locals didn’t know what to do with him when he began offering the same all-you-can-drink, ladies’ night-type deals. This was a luxury ski town, not the Upper East Side, and he had to ultimately tone things down. And yet, Ski Bar’s five-year run from 1990 until 1995 remains so memorable that close-knit regulars, many with adult children by now, continue to maintain a Facebook group to swap stories, and uniquely ’90s photos from the era.

In a way, it’s ironic Ski Bar continues to have such a strong presence on social media as Block figures social media is the very reason why you don’t see these types of bars and binge-a-rific drinking deals any more.

“One (Instagram) showing somebody stumbling out of your bar and you’re out of business,” he believes. Today he’s in his mid-50s and out of the bar business entirely.

Of course, it wasn’t just rising rents, Mayor Giuliani, and smart phones that would kill ladies’ night on the Upper East Side. High-end lounges and clubs were beginning to pop up downtown, especially around the flourishing Meatpacking District, and if plenty of ladies would continue to drink for free at places like Lot 61, Moomba, Spy Bar, and Marquee, it was the male customers who were usually paying for the overpriced bottles of Grey Goose and Patrón.

Likewise, by the end of the 1990s, the cocktail revival was just about to start in earnest in Manhattan — pioneering cocktail bars such as Angel’s Share and Milk & Honey would open in 1993 and 1999, respectively — and the craft beer and brewpub scene was in its infancy, and just about to explode in the aughts.

Even if it would attract the ladies, you couldn’t give away an $8 IPA, a $15 Old Fashioned for free. And that’s why Block thinks you’ll never again see an era like the early 1990s on the Upper East Side.

“Back then no one came in and said, ‘Let me see your bar menu,’” says Block. “$5 all-you-can-drink — that was my bar menu.”