It might not have received the attention it would have in the beforetimes, but when Torch & Crown Brewing Company opened its three-story, 9,000-square-foot space on the Avenue of the Americas in SoHo last October, it was still big news. Countless articles breathlessly discussed the difficulty, the insane logistics it took, the “massive engineering know-how” (according to InsideHook) to open what the press would continually call the first “production brewery” in Manhattan since 1965.

“I’ve lived in lower Manhattan my entire adult life,” says Torch & Crown co-founder John Dantzler. “But there wasn’t anyone making the beer here that I wanted to drink. It’s a major discrepancy that we’re in the most densely populated part of the country and there isn’t a brewery built to serve the community.”

That wasn’t always the case, however, by any stretch of the imagination. In fact, Manhattan used to be a hotbed for brewing operations. Especially in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

What happened?

When It Was Yuppie Beer

On a Thursday night in November of 1984, the Manhattan Brewing Company opened its doors on the third floor of a former Con Ed transformer station on Thompson Street in SoHo — “on a block that soaks up lots of bad vibes from cursing Holland Tunnel travelers,” according to New York Magazine’s David Edelstein — four blocks from where Torch & Crown currently stands.

The 5,000-square-foot space offered six copper brew kettles, including one that was 14 feet high, purchased from traditional European breweries located in the Swiss Alps, Bavaria, and the Black Forest of Germany. On opening day, the Emerald Society of the Police Department played a bagpipe rendition of “Amazing Grace” as a memorial to all the Manhattan breweries that had come (and gone) before it.

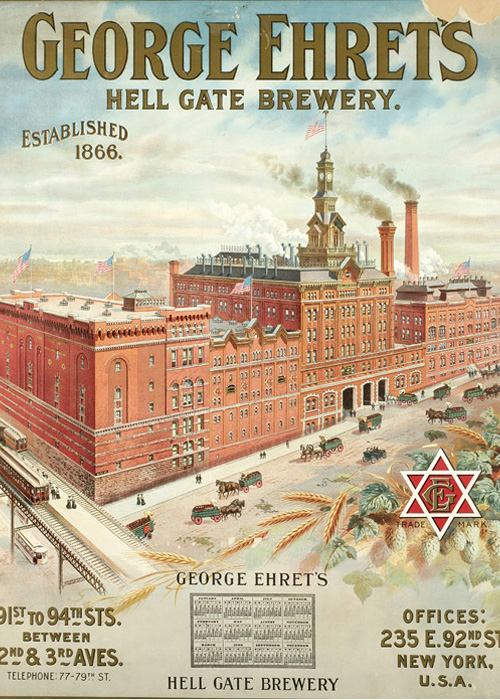

In fact, America’s literal first commercial brewery was opened in Manhattan in 1632, on what is now Stone Street in the Financial District. By the 1860s, the Upper East Side’s German-immigrant-heavy Yorkville neighborhood offered a slew of breweries like George Ehret’s Hell Gate Brewery, the largest brewery in the nation at the time — so massive it had its own well pumping 50,000 gallons of fresh water daily. Nearby was the George Ringler Brewery. Farther uptown sat the John Eichler Brewing Co.; farther downtown you’d find Central Brewing Company, F.M. Shaefer, and Elias Henry Brewing

Ehret’s chief rival, Jacob Ruppert, opened his eponymous brewery across the street from him. By the early 1900s it employed 1,000 workers, produced 2 million barrels of beer per year (including its Knickerbocker Lager), and was said to be worth an astounding $30 million. Spread across four blocks and 27 buildings — including a German-style beer hall — it closed for good in 1965.

But that doesn’t mean there wasn’t another brewery in Manhattan until Torch & Crown. Because for a good chunk of the 1980s and 1990s, Manhattan was lousy with places brewing beer: the relatively recent invention known as brewpubs.

Manhattan Brewing Company was opened by 37-year-old British entrepreneur Richard Wrigley who, at the time, was running Wollman Rink in Central Park, and mocked American macro beers as tasting like “soft drinks.” It was not only New York’s first brewpub, but the entire East Coast’s. (There had been exactly three brewpubs nationwide in 1983: Bert Grant’s Yakima Brewing and Malting Co. as well as Mendocino Brewing and Buffalo Bill’s in California.)

Manhattan Brewing employed English brewers who had formerly worked at Bass and Samuel Smith’s, like Mark Witty. But Wrigley was the self-professed visionary, claiming he did everything from conceiving each beer’s flavor profile, to designing the bottles and labels, to even installing the beer taps. “Saves money,” he told New York Magazine in 1984. As did living in the apartment above the brewpub, which Wrigley also did.

Manhattan Brewing’s British-style ales were fermented in traditional oak casks repurposed from Bass. They brewed about 60 barrels a day split between two ales, one lager, and occasional special releases, like a porter inspired by George Washington’s recipe, which was in the collection at the New York Public Library. And absurd as it may sound for 1980s Manhattan, these beers were delivered to around 200 outlets in the city via a horse-pulled Whitbread beer wagon. Meanwhile, the brewpub space offered beer cellar–style tables, peanut shells on the floor, and hand-pulled cask ales at the bar, which cost $2.50 a mug. It attracted a finance crowd and college kids, as the drinking age in New York was still just 19.

“They had a line down the street and around the corner every day for a long time because they were the only place where you could get real beer,” recalls Garrett Oliver, who had just returned to New York from living in London, where he had fallen in love with a good pint and started homebrewing. He would eventually begin apprenticing there.

At the time, the most popular microbrew in Manhattan was New Amsterdam’s Amber Lager, which was actually contract brewed up at F.X. Matt in Utica. But contract brewing wasn’t a term that Manhattanites knew or cared about back then (it’s arguable if they still care today). New Amsterdam Amber Lager sold for a lofty $9 a 6-pack, generating $1.2 million in sales in 1983, and was voted the most popular lager at 1984’s Great American Beer Festival.

“This is yuppie beer,” owner Matthew Reich, a former Hearst exec and wine lover, told The New York Times in February of 1985, and that was considered a good thing.

That same year he teamed up with a venture capital firm and raised around $3 million to open the 110,000-square-foot Old New York Brewing Company on West 26th Street and 11th Avenue, then an area most populated by prostitutes. Mayor Ed Koch pulled the ceremonial first draft at its 150-seat restaurant, The Tap Room, which was designed for an upscale diner, selling quiche and $16 steaks (about $40 in today’s numbers).

“The move by New Amsterdam heralded a sea change in the perception of craft beer as a business model,” writes Tom Acitelli in his excellent “The Audacity of Hops: The History of America’s Craft Beer Revolution.” “Partner with private equity or venture capital, and pull the tap on serious cash flow!”

Remarkably, by 1986, The Brewers Digest listed New Amsterdam as the best-selling microbrewery in all of America, with a barrelage nearly twice that of No. 2 Sierra Nevada. But this success wouldn’t last long, and the cash flow would quickly turn into a hemorrhage for New Amsterdam, which was losing around $100,000 a month by 1987. That was despite its sales booming — it raked in $2.2 million in 1987 alone, selling beer in over 1,000 locations throughout the metro area. Reich eventually had no choice but to shutter his Manhattan brewery and return to Utica.

“The costs of operating in New York City were heavier than we ever imagined,” Reich claimed at the time. “Everything costs more here, from the security costs down to the cost of parking. Do you know that the city charged us $750 a month just to lease a small parking lot? Where else would you have to pay that kind of money to park?”

Despite Oliver having quickly turned from an apprentice into a hot shot brewer, Manhattan Brewing would soon face the same struggles, heightened by the Black Monday stock market crash in October of 1987 and the raising of the drinking age to 21 at the end of 1985, which eliminated a good portion of their customer base.

In 1992 Wrigley tried to sell his brewpub for a mere $1 (it had $2 million in debt attached to it), but he would struggle to find any takers.

Take Two!

In Sinclair Lewis’s 1922 satirical novel “Babbitt,” its titular character is a realtor stuck in a hell hole of middle-class conformity named Zenith, or “Zip City,” an indistinguishable Midwestern town. Babbitt’s friend Paul Riesling is even more unhappy, feeling he has wasted his life and why didn’t he pursue that boyhood dream of becoming a violinist? Soon, both men begin rebelling against their bland lot in life in various ways.

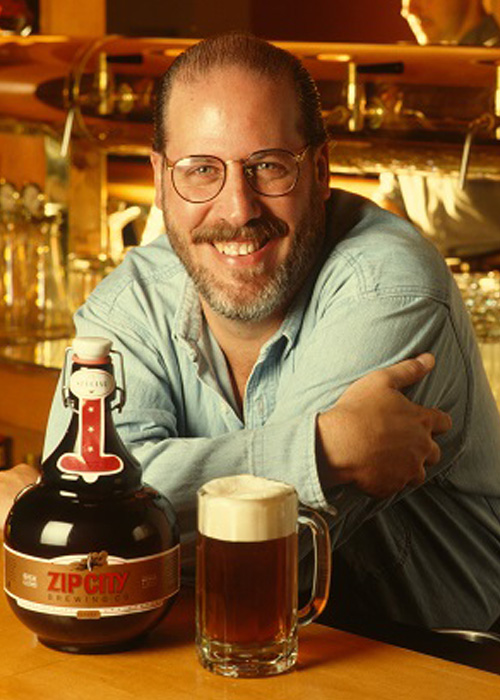

With that allusion in mind, Kirby Shyer opened Zip City Brewing Co. in 1991. It was located in the same building that had once been headquarters for the National Temperance League on 18th Street and Fifth Avenue. Shyer had come from his family’s eyeglass manufacturing business in Queens and decided to break free and do his own thing.

Zip City was stunningly beautiful, with a two-level mezzanine layout, wooden floors and booths, exposed brick walls, and copper tanks on display in the center of the room, surrounded by an oval bar, an aesthetic choice that would quickly be copied by others, including Torch & Crown today.

Brewmaster Jeff Stillman (and then later Jack Streich) focused on German-style beers, like dunkels, eisbocks, and wheat beers served in a tall pilsner glass with a slice of lemon, another popular aesthetic for this era. Food was elevated, too, with wild boar sausage nachos, yellowfin tuna chili, and beer crust pizza.

Edelstein wrote that “it makes you feel as if you’re wearing a suit and tie.” Indeed, Zip City not only attracted a finance crowd but regular celebrities like Julia Roberts. For several years it earned money hand over fist, so much so that Shyer was even planning to open Zip City II upstate in Peekskill.

“We don’t know what the saturation level would be here, but if they have 20 brewpubs in Portland, Oregon, there’s surely room for more in New York,” noted Tony Forder, the editor of Ale Street News, a newspaper covering the Northeast brewing scene, at the time.

In 1993 West Side Brewing Co. opened on the Upper West Side, initially with lagers so bad customers were offered fruit syrups to cover up the funky yeast. By the next year they had improved enough to be drunk sans syrup, with a caramel malt Gnarly Ale, a Nut Brown Ale, and Wheat Ale, though Edelstein did compare their Raspberry Wheat Ale to carbonated Robitussin. And, yet, that was enough for them too to plan a second brewery on Pier 59 in the new Chelsea Piers development.

Across Central Park, The Yorkville Brewery would open in 1994, eventually spinning off a sister Carnegie Hill Brewing Company, which produced beers like Urban Ale, a lightly hopped amber. By 1996, Florence Fabricant was writing that New York was “becoming as serious as Seattle is about beer.” That year, according to The New York Times, at least 10 breweries would open in Manhattan.

No longer was it just German-style or English-style beers, either. Bayamo was a Cuban-inspired brewery near Washington Square Park. In midtown, Typhoon Brewery opened on East 54th Street with a Pan-Asian menu by Jean-Georges protégé James Chew. The Commonwealth Brewery, an offshoot to one Wrigley had launched in Boston, opened at Rockefeller Center a few months later. Both were looking to reel in moneyed power-lunchers.

“We want to cater to executives,” said Commonwealth co-owner Joe Quattrocchi, who had partnered with Wrigley.

There was by then a magazine, New York City Beer Guide, with an accompanying website that kept an updated list of what beers each brewpub was currently serving. On the radio, broadcast to 7.5 million listeners in the Tri-State area, was “The Beer & Food Show” with Terry Soloman, America’s first weekly craft beer broadcast. In the summer of 1996, a New York City Brewpub Crawl Marathon was able to stop at 12 different brewpubs in Manhattan, including Nacho Mama’s Brewery, opened in the former Manhattan Brewing space.

Additional brewpubs, like Hansen’s Times Square Brewery (which would serve German and British beers and food), A.J. Gordon’s Brewery, Chelsea Brewery, and Heartland Brewpub had just opened as well. Manhattan’s brewpub scene was as hot as a city’s could possibly be.

And then, just like that… it was all gone.

Some blamed cost of operations, others blamed a flooded marketplace, Shyer blamed the brutal winters of 1995 and 1996. The real problem, in retrospect, was that most of the beer was god-awful, and no Manhattanites wanted to drink it.

“Some of the beer out there is literally undrinkable,” claimed Jerome Noll, a lawyer and brewpub consultant at the time. Quattrocchi claimed he didn’t even drink his own. “I drink Rolling Rock and Budweiser,” he admitted to The New York Times in 1997. His brewpub would be closed by 2001.

End of an Era

Depending on what stats you read at the time, the failure rate of American brewpubs in the mid-1990s was as good as one in 15 or as bad as one in seven. The failure rate in Manhattan, of course, would eventually be one in all.

Zip City closed in April of 1997, and the next month Shyer had to pour 3,100 gallons of his Belgian tripel down the drain, under the watchful eye of an ATF agent. According to Wall Street insiders at the time, the allure and novelty of microbrewed beer was gone in New York City. It was so ubiquitous you could now find bottles of it in the local bodega; no need to venture to the actual place it was being made to pay $7 for a pint.

“The real problem is that I don’t think New Yorkers have made brewpubs a part of their day-to-day life, like people have in other cities, like Boston, Colorado, or the Pacific Northwest,” claimed Shyer who, after stints at InBev and a local beer distributor, finds himself back in the eyeglass business these days. (Should I note that Babbitt eventually returns to his “old” life by the end of the book?)

After Manhattan and Commonwealth, Richard Wrigley went on to open (and close) future brewpubs in Seattle (“The interior of the pub/restaurant is spectacular. The beer is not,” wrote one reviewer) and even Japan.

Meanwhile, Reich’s ambitious approach may not have worked for long in Manhattan, but he inspired an entire generation of brewing entrepreneurs, including Jim Koch, who would open Boston Beer Co. in 1985, and Steve Hindy and Tom Potter, who would launch Brooklyn Brewery in 1988 after contract-brewing at F.X. Matt initially.

Joining Hindy and Potter was Oliver, who finally left the borough of Manhattan to become Brooklyn Brewery’s first- ever brewmaster. He would help design and build the brewery in a former matzo factory in Williamsburg before it opened in 1996. His move from Manhattan across the river would perhaps foretell Brooklyn as the soon-to-be mecca of New York City brewing — today the borough has over 20 breweries.

By the time I arrived in Manhattan, fresh-faced from Syracuse University in the late summer of 2001, all that was left in the borough were Chelsea Brewing Company and Heartland Brewery, which at the time had six brewpub locations. Neither was particularly exciting, still serving beer styles from a past era like honey porters, apricot ales, and, yes, those hefeweizens adorned with a lemon wedge.

By 2002, Heartland had moved all its brewing operations to Brooklyn as well, the on-display brew tanks in the bi-level spaces now nothing more than museum pieces.

By 2014, with little fanfare, Chelsea Brewing closed shop and moved to the Bronx — apparently the rent had gotten too damn high.

And Yet…

Dantzler feels this is a better time than ever to start a brewery in Manhattan.

Despite having to navigate the insane bureaucracy of Manhattan, everything from city agencies and utilities companies to the Department of Buildings. Despite the difficulties in getting permits. Despite the unexpected $200,000 cost of having to build an 18-story boiler chute before opening. Despite the even more unexpected cost of installing a $250,000 precipitator for filtering kitchen smoke and grease particles out of the building. Despite the fact that, by his estimation, it costs over two times more to open and run a brewery in Manhattan as compared to, say, Brooklyn. Despite opening in the height of a pandemic, when the city is supposedly “dead.”

Dantzler feels he can succeed in Manhattan. That’s because many things have changed since the ‘80s and ‘90s. For one, customer knowledge.

“They were fighting a very different battle [in the 1990s],” says Dantzler. “They had to convince customers that better beer even existed. We are fortunate, we are introducing the city to Torch & Crown, but not introducing them to the entire category of craft beer.”

Even more important has been legislative change, notably the farm brewery law and Craft Beverage Modernization and Tax Reform Act of 2013 and 2015, respectively. Overnight, in Dantzler’s opinion, New York went from one of the worst beer states to one of the best. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, if you were a brewpub, you couldn’t distribute beer or sell it to go. And if you were a production brewery, you couldn’t serve beer on site.

Torch & Crown not only sells cans and kegs of its beers like Almost Famous, an IPA, and There Goes the Neighborhood, a barrel-aged imperial stout, to bars and restaurants across the five boroughs (as well as online to consumers thanks to new pandemic rules), but it has a three-story Kushner Studios-designed restaurant space with high, ivy-covered walls and seating for over 400.

“We thought if we put a brewery in an area that is physically accessible to a lot of people, we stood to gain a lot,” says Dantzler. “We’ve got millions of consumers who live in Manhattan and we have a rare market opportunity to appeal to a much broader category.”

Already he’s noticed his customers’ gender split is about 50-50, and it’s a more diverse crowd, too; way different from the standard white male beer geek crowd he notices at most breweries in Brooklyn. Most importantly, however, in Dantzler’s opinion, is the Manhattan mindset, that knowledge that you can do anything and get anything you want at any time you want on this 23-square-mile island — and it’s always going to be top-notch to boot.

That’s the biggest reason Dantlzer opened in Manhattan, and the biggest reason he thinks Torch & Crown will ultimately succeed.

“We have world-class everything right around us: restaurants, cocktail lounges, entertainment,” says Dantzler. “If we’re thinking about capturing people’s attention, we’re surrounded with lots of other world-class offerings. Everyone knows Manhattan gets the best of the best,” he adds.

“And we are the only brewery.”

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!