Last month, the CANarchy Craft Brewery Collective announced the launch of a brewpub that will take over the Lexington Avenue Brewery (LAB) in Asheville, N.C. Dubbed the CANarchy Collaboratory, the space promises to be a one-of-kind brewery and creative hub where brewers, chefs, artists, and musicians will cocreate under one roof.

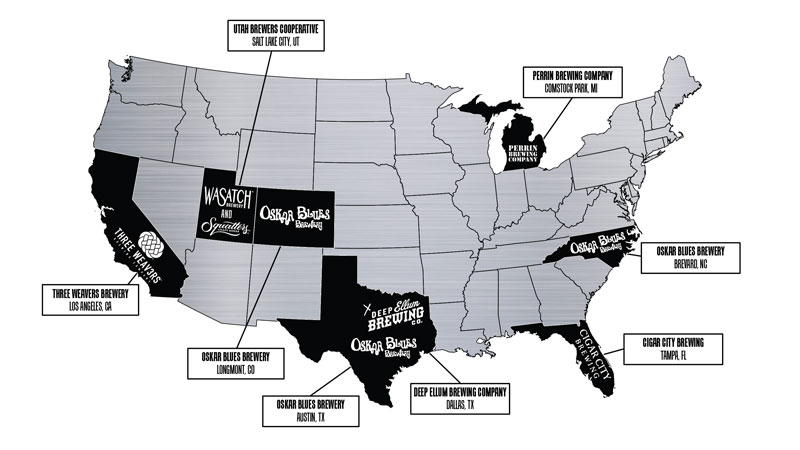

CANarchy, established in 2015, currently includes seven breweries: Oskar Blues, based in Longmont, Colo.; Cigar City of Tampa, Fla.; Three Weavers of Inglewood, Calif.; Perrin of Comstock Park, Mich.; Deep Ellum of Dallas; and Utah Brewers Cooperative’s Squatters Craft Beers and Wasatch Brewery, based in Salt Lake City. The group purports to be a “disruptive collective of like-minded brewers dedicated to bringing high-quality, innovative flavors to drinkers in the name of craft beer.”

Of course, no collective stands alone. CANarchy is backed by Fireman Capital Partners (FCP), a private equity firm helmed by the founder of Reebok.

The partnership raises several questions for craft brewers and drinkers: What’s the founder of Reebok doing investing in beer? What’s so “disruptive” about being funded by a private equity firm? And, ultimately, what does the future hold for CANarchy’s individual brewers?

“Those are really hard questions to answer,” Matt Fraser, CANarchy president and COO, says. But, he adds, “What we’re doing is working.”

That much is certain. Its success has been spelled out in a succession of brewery acquisitions, production volume increases, and distribution growth. But with success comes scrutiny, especially as the lines between “craft” and “not craft” — and the very definition of a craft brewer itself — continue to change as the industry evolves.

But beer fans would be remiss to write CANarchy off as another “evil” empire destined to squash creativity. It’s not here to minimize consumer choice, nor to flip beloved breweries like Boca Raton condos.

Instead, its “independent, together” motto, and yes, financial backing, give growing brewers the boost they need to thrive. With more breweries opening and closing every year, and competition coming from both conglomerates and cool-kid can releases, CANarchy is finding a way to strengthen the industry, one acquisition at a time.

FCP, PE, and CANarchy

FCP was founded in 2008 by Dan Fireman, son of Paul Fireman, former chairman and CEO of Reebok International Ltd., a brand which, according to his company biography, he “created and managed” from 1979 until 2006, when he sold the business to Adidas.

Prior to founding FCP, Dan Fireman served as CEO of a condominium complex in New Jersey, and co-founder of a golf course in that state.

FCP’s first foray into the beer business was in 2012, when it purchased a majority interest in the Utah Brewers Cooperative, a company comprised of Wasatch and Squatters breweries. Meanwhile, Oskar Blues founder Dale Katechis was searching for ways to expand his own operation. Katechis and former West Side Distributing owner Keith Klopcic were angling to acquire Perrin Brewing when FCP came knocking.

“Never in my wildest dreams did I think I was going to do business with a private equity firm,” Katechis said in an interview. “I thought they were guys that had horns and came in and … ran away with all your money. [But] you don’t have to rip anything apart if you both have aligned interests.”

In March 2015, FCP invested nearly $133 million in Oskar Blues, becoming a majority investor. With FCP’s help, Oskar Blues acquired Perrin Brewing shortly thereafter. With four breweries between them, Fireman and Katechis saw a larger, long-term opportunity to unite similar breweries across the country that sought mom-and-pop ideals but had outgrown their hometowns. In other words, breweries that needed to reach more markets to survive, but not willing to compromise their “independence” to do so.

FCP and Oskar Blues formed the CANarchy Craft Brewery Collective in 2015. In 2016, CANarchy acquired Tampa’s Cigar City in a deal valued at $60 million.

The cash kept flowing. By July 2017, FCP raised a new fund of $200 million.

Friends With Benefits

The CANarchy vehicle hit the pavement in 2015, and now works with 200 distribution partners across 50 states. Perks for brewers abound.

“We provide support, work together on raw material purchasing, can pricing … and consolidate IT, HR, accounting, banking, excise tax reporting,” Fraser says. In short, he says, “It allows us to be infinitely local and nationally accessible.”

CANarchy is now the ninth-largest craft brewery by sales volume in the U.S. It’s the largest supplier of independent craft beer in a can, and produces the two top-selling canned craft beer 6-packs in the country, Cigar City Jai Alai IPA and Oskar Blues Dale’s Pale Ale. In 2017, Cigar City doubled its out-of-state distribution and nearly doubled production, increasing shipments 43 percent from 65,000 to 92,000 bbls. In the same period, Oskar Blues increased production by 20 percent at its brewery in North Carolina, and grew total multi-outlet and convenience store sales by nearly 10 percent. Also in 2017, Perrin saw 20 percent growth in its home state of Michigan, and 22 percent growth in retail sales in IRI’s Great Lakes Region.

“It’s really cool to be able to pick up the phone and have those guys on your team,” John Stewart, Perrin’s director of brewing operations, said in an interview.

Selling vs. Selling Out

But some have criticized CANarchy, comparing its path to Anheuser-Busch’s High End, which acquired such brands as Goose Island, 10 Barrel, and Wicked Weed; or to similar mergers and acquisitions between Constellation Brands and Ballast Point, Heineken and Lagunitas, or Mahou San Miguel and Founders. In other words, according to some critics, selling one’s brewery to a private-equity-backed vehicle looks, smells, and acts a lot like “selling out.”

“Fireman Capital Partners just purchased Cigar City Brewing,” wrote the Washington Beer Blog on Facebook in March 2016. “So Cigar City is the latest to join the ranks of The Acquired. Does anyone care anymore?”

“Isn’t the CANarchy deal almost exactly like the The High End, the bought-up craft breweries in AB InBev’s stable?” Lew Bryson wrote on his blog, The Full Pint, in August 2018.

“It’s a hard question to answer,” Fraser says. CANarchy “look[s] at FCP as a founder,” meaning it and its partner breweries each own “a significant share” of the business, he says. As the collective grows, each founder’s portion of the business grows. For example, he says, “[Cigar City founder] Joey Redner owns just as much of Cigar City as Three Weavers.”

Additionally, CANarchy’s business model differs from brewery networks like Craft Brew Alliance, Boston Beer, and North American Brewers. Those are publicly traded companies, meaning shares can be divided among thousands of shareholders, rather than only the brewery founders.

It’s also “pretty different [from] traditional private equity” in that there is no three-to-five-year hold, meaning FCP isn’t preparing to flip its shares in the short term. “[FCP] can hold a business for five, 10, 20 years,” Fraser says. “Everybody’s joined the collective because of the long-term hold strategy.”

“We’re going to design this in a way, in a vehicle, in which it doesn’t have to ever exit,” Fireman told The Boston Globe in 2016.

And as far as investors go, Fireman takes an active approach. He serves on the boards for three FCP partners, including CANarchy. The others are Dunn’s River Brands, a “strategic beverage platform” of bottled tea brands The Sweet Leaf, Tradewinds, and Temple Turmeric; and Surfside Coffee Company, a Dunkin’ Donuts franchise network in Florida.

Long-term or short-term, though, return on investment is the ultimate goal of any firm, be it a middle-market fund or a Main Street stationary shop. Corporate or cooperative, no business can continue without earning money. In FCP’s 10-year history, the firm has “realized” — a self-helpy euphemism for “sold” — six of its partners. None involved beer.

If FCP sells its stake in CANarchy — say, to the very machine it protests, ABI — or shifts to a private equity-backed IPO, the future of its breweries could be at stake. “Could something happen down the road? Sure,” Fraser says. But for now, “we’re not pressured to do anything.”

There’s No ‘I’ in CANarchy

Where the CANarchy vehicle goes next is a matter of geography. “We want to continue growing organically and inorganically,” Fraser says. Gaps in the map, like the Northeast, Chicago, and Pacific Northwest, are likely targets. The goal is “having a network of facilities across the U.S. [to] manufacture flagships,” he says. “There [are] a lot of people on the wish list.”

A group simultaneously celebrating anarchy and synergy can be hard messaging for savvy beer consumers to swallow. Just as we roll our eyes at BrewDog’s “equity for punks,” or frown at our favorite indie band signing with an international label, a business strikes us as no longer subversive once it is corporate.

Maybe that’s O.K. CANarchy was “born out of a need and an opportunity,” Patrick Daugherty, CMO, says. It’s proving that a private equity-backed, team-like model succeeds at economic and emotional levels, allowing both brewers and their fans to celebrate a strengthened beer industry while simultaneously sticking it to the man.

In the last year and a half, Green Flash Brewing, a beloved top brewery, saw expansion outpace its demand. It shuttered two locations, pulled distribution from 42 states, and laid off 76 employees. Last week, Deschutes Brewery, the 10th-largest craft brewery in the country, cut dozens of employees. Even the most successful breweries can’t predict their survival.

Whether CANarchy’s brewers are as “disruptive and irreverent,” as they say, doesn’t matter. For consumers, not to mention brewers, what matters most is that we have access to and agency in quality beer.