The phrase “California Wine Country” often conjures images of rolling hills, perfectly manicured rows of lush green grapevines, and beautiful people sipping Chardonnay on balconies. It doesn’t evoke images of abandoned mines, dirt roads, and tree-sized grapevines with gnarly arms and wild leaves nestled between tiny towns with triple digit populations.

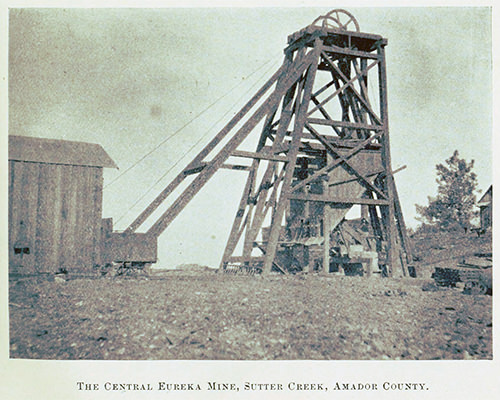

Welcome to Gold Country. The vast, parched stretches of the lower Sierra Nevada defy common notions of California as a populated state full of bottle blondes and fancy wines. The winding, forested roads of Amador and El Dorado counties, just an hour outside the capital city of Sacramento, still leave discovery up to the driver, unlike the pristine, organized chaos of the Silverado Trail or other more popular wine routes. Here, in a region that’s been largely forgotten, a different type of wine industry has taken root–one characterized by jean-clad workers and simple tasting rooms, where wine pourers are often the winemakers.

The gold-filled stream beds that sent swaths of immigrants to California in search of the Mother Lode in the 1850s and 1860s gave way to a unique wine industry dominated by Old World grape varieties like Zinfandel and Barbera.

At its heart lie the picturesque towns of Volcano, population 97, and Sutter Creek, a veritable metropolis in comparison, with its population of 2,400. Volcano was the discovery site of the massive gold stores, the country’s first solar still, and was nearly voted the sate capital. Now, you can discover the Union Pub & Inn, a haven for local wines and brews nestled on a quiet corner, surrounded by roaming chickens and fields of cattle.

In nearby Plymouth–formerly the gambling haven known as Pokerville–the oldest Zinfandel on the continent still thrives. The vineyard dates back to 1869 and produces world class Zinfandel, though the vines more closely resemble trees with their thick trucks and gnarled arms, rather than the petite and orderly vines that criss-cross the landscape, most of which joined the area within the past twenty years.

The soaring prices of Napa and Sonoma land over the past two decades has sent intrepid winemakers searching for vineyard space elsewhere, turning Amador from a county of 7 wineries to one of 43 in 2014.

If Zinfandel is the pioneering grape of Gold Country, then Rhône-style wines like Grenache and Syrah are the Millennials. Rhône Rangers, like winemaker Bill Easton of Terre Rouge and Easton Wines, have long championed the iron-filled and volcanic patchwork of Amador soils as a hotbed for rich Rhône-style wines.

Similarly, Sharon and Greg Baiocchi, owners of Baiocchi Wines, are pumping out wines that are anything but dainty, and more modern than Sutter Creek’s historic Main Street would suggest. The highlight is their 2011 Nicholas Vineyard Syrah, a deep and brooding wine with all the herbal tones of the Northern Rhône, but the bold, full-body of an American wine. Think Carla Bruni meets Beyoncé.

Climbing higher into the hills, past the so-kitschy-its-cool Roaring Camp Miner’s Village, noted Napa viticulturist Anne Kraemer’s ranch covers 50 rolling acres. It’s tucked away such that to find Shake Ridge Ranch, you’ll have to turn sharply off the road, and drive through two gates with livestock warning signs before the towering pines disappear to reveal rolling hills covered in vines. Kraemer’s Yorba label consistently sells out in her tasting room, but these grapes often make it into well-known juice under other names, such as Favia Wines Suize Viognier and A Tribute to Grace Shake Ridge Grenache.

The largely undiscovered aspect of Gold Country means these wines continue to offer fantastic value to consumers, especially against other American wines. Often priced in the twenty-dollar range, they can cost up to 50% less than similar California counterparts. So while the hunt for gold may no longer be relevant, Gold Country continues to thrive as a vibrant wine-producing region. The Mother Lode is still delivering.