Joe Coughlin’s day starts quietly, as the sun rises and lights the vine-covered hillsides that define much of Northern California’s landscape. These are the only quiet moments he’ll likely have until October as the Assistant Winemaker at Amador County’s Sobon Estate Family Winery, where winemaking is a small part of the duties he performs during harvest. A more accurate title might be “Forklift Driving Scale Manager Laboratory King.”

I developed that catchy title after Coughlin graciously allowed me to chase him through a hectic harvest day, determined to document the True Life version of a winemaker at crush time.

“As soon as I get here, around 6:30 am, I start putting the game plan together,” said Coughlin, referring to his calm thirty minutes at the winery before staff and the day’s grapes arrive.

Coughlin’s crew doubles to six in August, and arrives promptly in the accepted uniform of stained t-shirts and well-worn jeans. “These guys work from 7am until everything is done” he said. “We have a quick pow-wow when they get in, and I usually get them started cleaning something before fruit arrives.”

By 7:30 Coughlin is on the crush pad, weighing Primitivo from a local vineyard ton by ton on a scale big enough for a horse.

“Most people don’t realize that the government requires you to account for every pound of grapes and every single bottle of wine in this industry, down to the hundredth of a gallon. I spend a lot of time writing down numbers as a result.”

Around 8:00 am, the crusher and destemmer clank to life, and the Primitivo begins its journey to wine at 25 tons per hour.

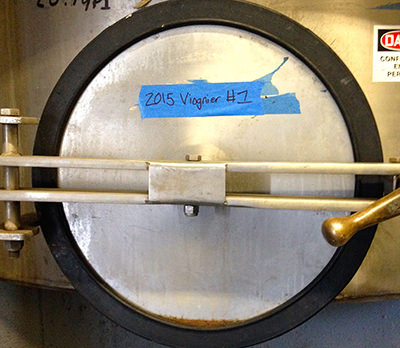

As the sweet purple grapes make their way into massive temperature-controlled tanks, harvest staff move through the winery like bees in a hive, washing presses, prepping tanks, and taking measurements on fermenting grape musts.

After an efficient phone call with head winemaker and owner Paul Sobon at 9:00 am, Coughlin redirects freshly crushed grapes to a different 3,000 gallon tank, quickly calculating the final blend of the wine.

Before he can explain the details, Sobon pulls up to the winery with four more tons of Zinfandel. Like synchronized swimmers, Coughlin and Sobon shift half-ton bins of grapes from trailers to the scale and hopper to keep the crusher moving constantly. The estate produces about 60,000 cases of wine annually, with over 100 tons of fruit arriving in a few short weeks, making efficiency crucial.

“What most people don’t realize is that the older wines don’t just disappear when harvest starts,” explained Coughlin as we headed from the sunny crush pad into the humid, chilly cellar. Older wines still need to be maintained, he explained, and that requires everything from sampling and lab tests, to keeping barrels full to the brim.

At 10:00 am, it was time to sample the fermenting juice already midway through its journey to a dry, finished wine.

“What we’re doing is logging the progression of the fermentation, and by looking at the temperature we can see the speed of the fermentation and whether it needs to be adjusted,” Coughlin said, explaining that the worst case scenario is a “dead” fermentations where yeast have died. “Restarts are the worst because we have to use really killer strains of yeast…Hopefully we don’t have any of those.”

Tank by tank, Coughlin pulls samples into 20 oz. Ace Hardware buckets, tasting from each one to see how the wine is progressing, letting me sample the candy-like juice alongside.

“Don’t taste for sweetness,” he says, “We’re looking for fruit qualities and acidity behind the sweet.” Next, more technical measurements than our tastebuds are taken, during which Coughlin dashes from his tiny office to avert a crush pad crisis.

By 11:30, the samples are done and everyone on staff seems to collapse.

“You need a nap,” says Kristie Kendrick, a 2-year harvest veteran at Sobon.

“I need a martini,” says Coughlin, his eyes already closed, admitting it’s his 12th straight day on the job. And that was lunchtime.

The afternoon entailed another cycle of testing new and existing fermentations for pH, sugar, and acidity levels to determine if any additions – acid to prevent bacterial growth, tannins for texture, oak chips for complexity – were necessary. Like worker bees in the proverbial hive, Coughlin and his staff buzzed incessantly from one post to another, constantly monitoring equipment and wines.

All the while, the crusher continued, squishing roughly 50 tons by 4:30.

“Wash, rinse, repeat,” said Coughlin, “I’ll be here tomorrow.”

And every other day for the next six weeks.