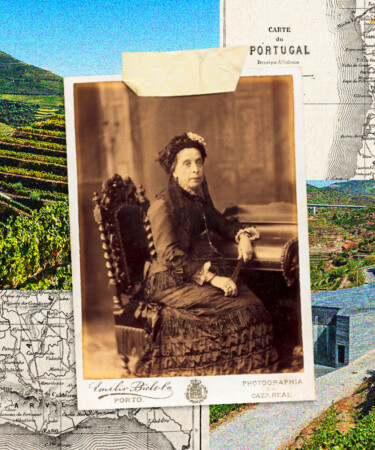

Looking back on the history of wine, we find that women often played a larger role in the shaping of major regions than they’re given credit for. One now well-known example is Madame Clicquot, who took the reins of her family’s Champagne house when her husband François passed away in 1805. She was known for her cunning intellect and fearless approach, taking risks to grow the business. Clicquot invented the riddling table, created the first blend of rosé Champagne, and played an essential role in the expansion of Champagne as a global product — earning her the title the Grande Dame of Champagne. But while Madame Clicquot’s contributions to Champagne have finally been recognized — the brand’s name Veuve Clicquot literally translates to “Widow Clicquot” — there’s another woman who took her own nation’s wine to new heights and who deserves proper recognition. Meet the brilliant Dona Antónia Adelaide Ferreira, the remarkable businesswoman who changed the history of Portugal’s Douro Valley, and Port wine as a whole.

Dona Antónia was born into a prestigious family in 1811, and when she was widowed at the young age of 33 years old in 1844, she inherited the family business — the already massively successful Ferreira Port House, including all of its estates and grape suppliers. As an heiress to this Port fortune, Dona Antónia could have easily stepped back and focused on managing her wealth and existing estates. But instead, her passion for the Douro Valley inspired her to invest in the region and become a champion for the local wines and workers. Dona Antónia cherished the family’s values and culture, but also pushed for innovation. She implemented technology like new bottling systems at her wineries, keeping quality top of mind with every new development. She also became a respected negotiator and businesswoman, expertly navigating the male-dominated wine world.

Through her hard work, Dona Antónia became one of the most wealthy and respected figures in Portugal. However, this shining reputation led to some unwanted attention. Interested in their family’s massive fortune, the Duke of Saldanha, João Carlos Saldanha de Oliveira Daun, ordered that Dona Antónia’s 11-year-old daughter was to marry his son. Dona Antónia refused, maintaining that her daughter was too young and should marry someone she loved. The duke was displeased with the rejection, and sent the army to “convince” her. As she was a beloved figure in the region, locals warned her of the incoming soldiers. She courageously escaped with her daughter on a mule, dressed as a peasant, and traveled to England where she had good relations with the royal family.

When Dona Antónia returned to Portugal two years later in 1856, she found her wine region in crisis. In the 1850s, the oidium fungus spread throughout the Douro and destroyed many of the vineyards, and then in 1865, the dreaded phylloxera pest crept its way into the land. Throughout this difficult period, Dona Antónia focused on helping local farmers and keeping the region afloat. Since her family estates had large stocks of wine, she found a way to continue to make money by selling the older bottles, and reinvest in the region by buying up land from struggling farmers. She started projects to investigate viticulture and winemaking processes that could help overcome the plagues, creating jobs for those who were without work at the time. Dona Antónia’s efforts are credited with keeping the region alive until the solution for phylloxera was discovered.

Beyond strategically navigating the Douro through its most disastrous time, Dona Antónia also kept the far-off future of the wine region in mind, implementing ideas that still benefit her estates over a century after her death. This can be seen at one of Dona Antónia’s estates, Quinta do Vallado, which is still run by her ancestors to this day. João Álvares Ribeiro, the sixth generation of her family to work at the winery, often notes Dona Antónia’s impact on their business, particularly referencing her initiative to keep wines aging in barrels across her many estates, including Quinta do Vallado. During Dona Antónia’s time, all Port wines had to be both aged and bottled in Vila Nova de Gaia at the mouth of the Douro River by the city of Porto, according to the laws of demarcation established in 1756. If the wines were aged or bottled in the Douro Valley at the wineries themselves, they could not be labeled as Port. But as Ribeiro tells VinePair, “Dona Antónia was never one to follow the establishment.” She kept large stocks of wines at her wineries in addition to those aging in the Port house cellars.

“She thought this was a smart move as she knew aging Ports increase in value over time, so these would act like her ‘piggy bank’ in the Douro,” Ribeiro says. Roughly a century after she passed in 1886, the law was updated allowing producers to bottle wines aged in the Douro. “When my grandmother and her brothers inherited Quinta do Vallado in 1987, we were extremely privileged and lucky to have big stocks of very old Ports. Aging since the times of Dona Antónia, [they] can now be bottled as Port wines and shared with the world.” Now, the specialty Vallado ABF Porto Muito Velho from the 1888 vintage is available to purchase, a wine that would not be possible without her foresight.

Dona Antónia’s legacy lives on through the many estates that she helped build, as well as several awards and charities that use her name to honor her work as a humanitarian and important leader in the history of Port wine. She lived by the idea that “everyone should do all they can for the good of humanity,” and her work in business and charity have proved to help the people of her beloved region — even to this day.