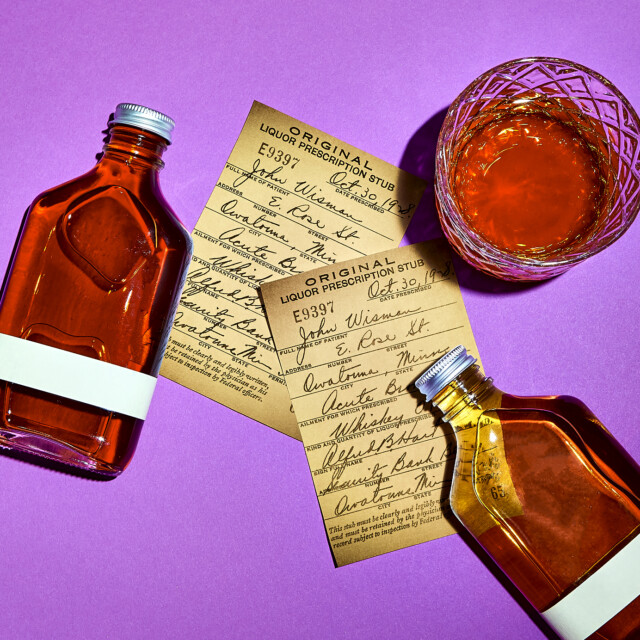

The 13 years of national Prohibition aren’t usually associated with high-quality spirits. Bootlegged and diluted whiskey, bathtub gin, and backwoods moonshine were indeed all consumed in great quantities in the era’s underground bars and speakeasies. But a lesser-known reality of Prohibition was that it was possible to legally acquire well-aged, bottled-in-bond bourbon and rye. All you needed was a prescription.

In the early 20th century, doctors and patients still believed that hard liquor had some curative properties. Although distillation was outlawed, an exception was made for a handful of distilleries to continue to bottle whiskey for medicinal purposes.

Prohibition remains one of the most romanticized periods in American history among drinkers. It’s common to see modern brands allude to this anomalous era when marketing their spirits — “Prohibition style” is a phrase that has been overused to the point where it’s almost meaningless.

Recently, however, a few high-profile releases from legacy distilleries have roused the interest of enthusiasts. In October, Buffalo Trace Distillery announced the Prohibition Collection, a set of five whiskeys inspired by the medicinal whiskeys of the Prohibition era. Intrepid whiskey enthusiasts also discovered the TTB filing for Old Forester 1924, an upcoming bourbon that will join Old Forester 1920 as another Prohibition-era whiskey in the brand’s Whiskey Row Series.

But what does a “Prohibition recipe” or “Prohibition style” even mean in modern whiskey terms? And how — if at all — are today’s producers able to replicate them?

What Did Medicinal Whiskey Taste Like?

When Prohibition was codified into the Constitution, distilleries were able to apply for a permit to sell medicinal whiskey. Six producers were granted these permits: American Medicinal Spirits; Schenley Distilleries; James Thompson and Brother, which later became Glenmore Distillery; Frankfort Distillery, which included the George T. Stagg distillery that is now known as Buffalo Trace; Brown-Forman; and Ph. Stitzel Distillery.

“Kentucky had a lot of prior notification before Prohibition happened. So a lot of bourbon was squirreled away,” explains Jack Rein, the executive director of the Oscar Getz Museum of Bourbon History, which has one of the largest collections of Prohibition-era medicinal whiskey.

The massive stockpile of aging whiskey held by producers was spread throughout the country, which complicated things for federal agents.

“The government realized there was no way they could control hundreds of rural warehouses and keep the whiskey from disappearing,” says Tim Holz, historian at Brown-Forman. So in 1922, the Concentration Act was passed. The act required that all existing barrels be moved into around 30 government-monitored “concentration” warehouses.

“What’s striking is that distilleries continued to package and promote their whiskey in a way that went above and beyond what a medicinal whiskey would entail.”

Both Brown-Forman and George T. Stagg Distillery wound up owning two of the concentration warehouses in Kentucky. “People who didn’t have the ability to bottle their whiskey sent it here,” says Nick Laracuente, bourbon archaeologist and archivist at Buffalo Trace. “We got whiskey barrels from all over North America.”

As the concentration warehouses began to fill with barrels, producers found themselves with a vast amount of quality whiskey, which started to make its way into medicinal bottles. “They weren’t taking advantage of the moment to sell rotgut,” says Clay Risen, journalist and author of “Bourbon: The Story of Kentucky Whiskey.” “You still saw 12-, 14-year-old whiskeys go into medicinal bottles.”

“A lot of that aging was essentially forced by Prohibition,” Laracuente adds. “They didn’t set out to bottle a 20-year-old whiskey — they didn’t really have a choice in it.” Whether intentional or not, the extra barrel aging and bottled-in-bond requirements meant that in many instances, medicinal whiskey was likely even better than if it had been bottled how the distilleries originally intended.

“What’s striking is that distilleries continued to package and promote their whiskey in a way that went above and beyond what a medicinal whiskey would entail,” Risen says. Trusted brands were still bottled as medicinal whiskey, and labels clearly advertised that the bottle contained quality whiskey and not just something that would be downed quickly as cough syrup.

Of course, each label would also contain the unenforceable warning of “for medicinal use only.” But it wasn’t fooling anyone — this whiskey was meant to be enjoyed. The producers understood this, pharmacies understood, and prescription-holding consumers certainly did, too.

Recreating Prohibition-Era Whiskey

From the very beginning of bottled and branded whiskey, producers have always relied on history to sell their juice. As far back as the late 1800s, producers like E.H. Taylor and George Garvin Brown hearkened back to simpler times as a marketing strategy. It’s a practice that remains common to this day, especially among up-and-coming producers trying to compete with legacy distillers. But the bigger brands aren’t exempt from such tactics, either, and often they do have genuine historical quirks to lean into.

“For [Old Forester 1920] the proof point is the storyteller: 115 is what we estimate the barrel proof was before diluting down to 100.”

Both Buffalo Trace and Old Forester were actively bottling whiskey before, during, and after Prohibition, so if any brands can claim to be using a recipe from that era, or bottling Prohibition-style whiskey, it’s them. And given they owned a large chunk of the medicinal whiskey market, it makes sense that both distilleries would highlight their existence during Prohibition.

Since 2017, Brown-Forman has offered the 115-proof Old Forester 1920 expression as part of the brand’s historically themed Whiskey Row Series. The series looks set to soon include Old Forester 1924, which, according to a recently uncovered TTB filing — thank you, online whiskey sleuths! — will be the first age-stated bourbon in the lineup.

This past fall, Buffalo Trace distillery announced the Buffalo Trace Prohibition Collection. Released in October, the collection consists of five different whiskeys, packaged in 375-milliliter bottles and cardboard boxes meant to emulate the pint bottles often prescribed during Prohibition.

Both distilleries have robust archives that contain sealed bottles from Prohibition among other documents and artifacts from the era. But even with their resources, just how much do the distilleries know about the flavor profiles of distillates from that era?

“We’re interpreting what was going on at the distillery during those years.”

Sealed bottles that were stored in perfect conditions can still change quite a bit over the course of a century. Due to evaporation and oxidation, whiskey bottled during Prohibition would not taste the same today as it did when bottled.

According to those who have tasted Prohibition-era whiskey, it’s still immediately recognizable as a bourbon or rye, but the oxidation and evaporation tend to lower the proof and change the whiskey’s character. So it’s almost impossible for anyone today to know for sure what the whiskey of that time period tasted like at the time.

But is that even the point?

“We’re not necessarily trying to say this tastes like Prohibition-era medicinal whiskey,” says Melissa Rift, Old Forester’s master taster. Brown-Forman’s master distiller emeritus Chris Morris did reference pre-Prohibition whiskey samples from the company’s archives when developing the Whiskey Row Series, but instead of trying to recreate century-old bourbon, Morris and the team at Old Forester opted to use their modern distillate to create whiskeys that reference moments in the brand’s history. “For [Old Forester 1920] the proof point is the storyteller: 115 is what we estimate the barrel proof was before diluting down to 100,” Rift explains.

From what little information has been publicly disclosed about Old Forester 1924, it appears that the distillery is taking the same approach for future releases. The label alludes to Old Forester bottling “different mash bills,” which could be a reference to Brown-Forman owning one of the few concentration warehouses in Kentucky.

In a similar fashion, each whiskey in the Buffalo Trace’s Prohibition Collection represents a brand bottled at the George T. Stagg Distillery after the Concentration Act was passed. Of the five whiskeys, Three Feathers, Golden Wedding, Walnut Hill, and Old Stagg were all brands that existed before Prohibition and were bottled at the George T. Stagg distillery. The Fifth, Spiritus Frumenti, is a reference to a generic medical term used to describe medicinal whiskey at the time.

“We’re interpreting what was going on at the distillery during those years,” Laracuente says. The labels and packaging for each whiskey come straight from Buffalo Trace’s archives. The modern versions have some minor changes because the TTB prohibits any claim of health benefits, but they are faithful recreations of the original designs.

All five “brands” are derived from the modern Buffalo Trace mash bills, but spend more time in barrel, are blended differently, and bottled at a different proof than most of the distillery’s readily available counterparts. Each also contains a whiskey that makes historic sense. For example, Golden Wedding was historically a Pennsylvania rye, so the modern 107-proof Golden Wedding is made from Buffalo Trace’s rye mash bill, which is the same recipe used to make the 90-proof Sazerac rye.

“With retro-style whiskeys, distilleries get to be artistic about it and that’s cool,” Risen says. “You have to remember to take it with a grain of salt. It’s not exactly a scientific thing.”

For whiskey enthusiasts who have an interest in history, the appeal is undeniable — whether these recreations are completely historically accurate or not. Medicinal whiskey might not be as glamorous as speakeasies and bootleggers, but it is certainly worth celebrating. For a few strange years, the best American whiskey available was being sold as medicine, and the modern distilleries that bottled it during Prohibition can be proud of that heritage.