One might rightly argue that many of the values America holds dear are directly reflected in the nation’s wine industry. American wine showcases a diverse range of grape varieties and styles, thanks to the country’s broad spectrum of climates. In American winemaking, innovation and individualism are celebrated, perhaps even actively encouraged, with producers working outside the shackles of overreaching regulations on the how, what, and where of viticulture and vinification.

Of course, these are neither original sentiments nor would you face much opposition were you to posit this definition of American wine to a sommelier, retailer, or winemaker. Idealistically convenient though they are, however, perhaps there’s an even simpler way to sum up the enological state of this union. Namely, that one state in particular overwhelmingly defines American wine: California.

With all due respect to the 16,000 bonded wineries operating across all 50 American states, the Golden State dominates all metrics by which the country’s wine industry can be measured. Again, this is not to discount the quality of Oregon Pinot Noir, Finger Lakes Riesling, or the dozen other regions and varieties you might be screaming at your screen right now. But it can also be argued that the status of those wines — and of American wine in general — remains largely indebted to the work and success of California winemakers since Prohibition’s repeal. Here’s why.

California Wine by the Numbers

To clearer understand just how much California dominates the American wine market, we should look at the tangibles, beginning with sales.

In the 52-week period ending Nov. 6, 2021, American drinkers spent a total of $20.3 billion on wine in the off-premise channels tracked by the data firm Nielsen. California wine accounted for 56 percent ($11.4 billion) of that total, and a staggering 82 percent of the amount spent on domestic wine ($13.8 billion). When viewed through the lens of volume sales, the latter share — California’s slice of the domestic pie — drops slightly to 77 percent.

It could be quickly pointed out that these realities arise directly from California housing multiple times more wineries and producing significantly more wine than any other state. And this is absolutely the case.

Last year, California produced 88.5 percent of all of the wine made in America, according to data from the Wine Institute. If we take that percentage and apply it to global volume data shared by the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV), California would have ranked as the world’s fourth-largest wine producer in 2020. Without the state’s input, America would sit in 15th place, between New Zealand and Hungary.

Where California is home to 6,010 bonded wineries, its nearest competitor, Washington, boasts a mere 1,389, per TTB data. It stands to reason that four of the nation’s five largest wine producers therefore count their headquarters in the Golden State, with New York’s Constellation Brands providing the exception to the rule.

There is a simple reason for this disparity, beyond California being the fourth-largest American state in terms of land mass, as California-based wine writer, educator, and consultant Liz Thach explains. “We have a perfect Mediterranean climate up and down the state, so wine grapes love California,” she says. “They also love Oregon and Washington, but the weather is more extreme in Oregon and Washington is cooler.”

California Wine, Beyond (Only) the Numbers

Up to this point, we have arrived with everything in perfect order, all the dots neatly connected. California’s climate and land mass make it the ideal place for thousands of wineries. In turn, those producers can — and do — dominate the market with the volume of wine they’re able to send to market.

But the problem with packaging everything in such tidy boxes and focusing quite so heavily on California’s advantages, is that these points detract from the finer details on how the state gained such dominance. And by extension, how California came to define America’s wine industry.

Without delving too deeply into the history of American viticulture, we should note that California was neither the first area where European settlers began making wine, nor the first to boast a governmentally recognized American Viticultural Area (AVA) — though the state is now home to over half of the nation’s 260 total. Put more simply, the state doesn’t profit from the historical advantage of being the first or oldest within America’s wine industry, as some might assume. (Those titles would go to Florida and Augusta, Mo., respectively.)

Another notable historic moment to briefly touch upon was the formation of the Wine Institute in 1934. Founded shortly after the repeal of Prohibition by groups of California producers and growers, the organization has had a significant hand in keeping the tax on American wine in check, and helped open up sales avenues for producers, such as DTC shipping. Composed of more than 1,000 California businesses today, the Wine Institute holds more than double the membership of the National Association of American Wineries, which represents producers in all 50 states.

But for multiple reasons, 1976 is the best point to begin a more in-depth historical exploration. This is the first year for which the U.S. Department of Agriculture offers a grape crushing report for California. In it, we learn that the state’s wineries crushed a total 1.2 million tons of wine grapes. Fast forward 25 years and that number more than doubles to 3 million tons. By 2018, following the largest harvest on record, California wineries crushed 4.3 million tons.

All of which is a less direct way of saying that California’s current status is not simply a byproduct of it having an “ideal” winemaking climate. The state has worked intentionally and effectively to grow its industry and develop a solid consumer base.

Now back to 1976, for this is a year many wine lovers will be familiar with thanks to the success of California wines in the now-legendary Judgment of Paris blind tasting. While often cited as the event that put American wine on the international map, the Judgment of Paris’s effects were just as significant on home soil.

California-based winemaker John Williams recalls a very different attitude toward wine in America when he arrived in Napa Valley on a Greyhound bus in 1974. “We were not a wine drinking nation,” he says. “My generation, and the half generation before me, did not drink wine. It wasn’t acceptable. It was considered a ‘sissy’ drink.”

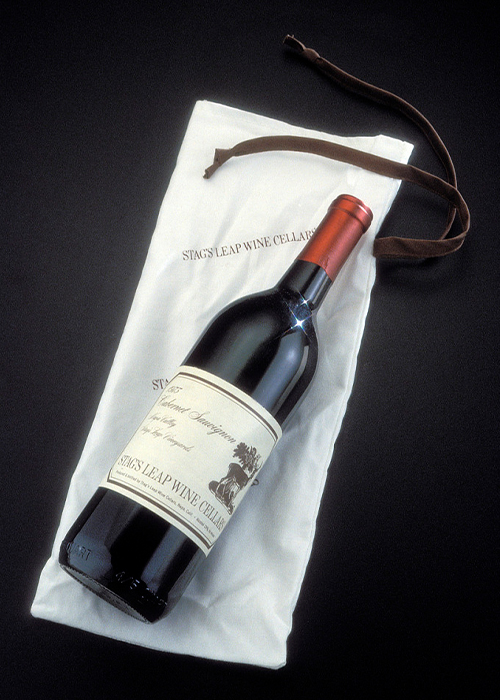

As a quick sidebar, Williams himself has a complex relationship with the Paris blind tasting. While he had a hand in one of the winning wines — Williams helped bottle Stag’s Leap Vineyards’ triumphant 1973 Cabernet — he’s also largely critical of the impact it’s had on the lack of viticultural diversity in modern-day Napa.

Still, the winning bottles caused many Americans to appreciate and take pride in the quality of their country’s wine, Williams says. “It kind of gave us permission to join the club of wine drinkers.” Drinking a Napa Cab at a steakhouse became a quasi patriot act — “We beat the French, god damn it! America!”

In the intervening years, Napa Cab would grow to become a global icon, with certain bottlings achieving a reverence akin to the finest first-growth Bordeaux and grand cru Burgundy. Meanwhile, the appreciation of American wine — both domestically and internationally — has forged a path for New York Riesling and Oregon Pinot Noir to succeed, Williams says.

That Napa and Sonoma have over the ensuing decades also developed a leading enotourism industry — not just in America but arguably worldwide — has only strengthened the ties between winery and drinker. And this offering extends beyond tasting room experiences, steam trains, and bocce ball courts.

Between them, Napa and Sonoma boast two of the nation’s 13 3-Michelin-Star restaurants. A further three restaurants hold that vaunted status in nearby San Francisco, while the city boasts 31 starred restaurants in total.

“Can any wine region be a fine wine region unless they have fine dining to go with their signature wines?” Williams asks. Certainly no other American wine region can compete on this front.

California, Beyond Fine Wine

Blue-chip Cabernets and multi-course tasting menus only tell half of the story, though. Because despite such luxuries, California wine also leads the way in terms of accessibility. “No one, except for Washington State, produces wines under $10 that are available all across the United States,” says Thach. “You have to have lots and lots of acres of vineyards in order to do that.”

California’s most popular wines at this price point don’t just compete economically, they typically offer mass appeal with “approachable” flavor profiles. And no style has made bigger waves in recent decades than the American red blend. Smooth-sipping and generous in their residual sugar levels, red blends such as Trinchero’s Ménage à Trois and E & J Gallo’s Apothic lead the way in the below-$15 tier, while Constellation’s The Prisoner arrives at the more premium $35 mark.

The added bonus of the popularity of these blends is the ability to avoid the tides of fashion associated with particular varieties. Should, say, a certain movie hit the big screen declaring that it’s suddenly barbaric to drink a specific variety — not a problem. “A lot of red blends have Syrah and Zinfandel, which are frankly not selling very well as single varietals,” says Thach. “There’s also a lot of Merlot in red blends.”

Additionally, the availability of such wines only magnifies the effect of California’s dominance when viewed through a final lens of foreign lands. For while smaller producers from lesser-known regions fight to gain national distribution, California’s behemoths fly the flag for their state and country worldwide.

This has ramifications beyond simple revenues, impacting the way the international wine trade views and learns about American wine. For example, the Wine & Spirits Education Trust (WSET), a British-headquartered international educational body, focuses the majority of its teaching materials within its American wine chapter on California (six of eight pages in the 2016 edition of the Level 3 Award in Wines textbook).

“When we’re looking at wine education from a global perspective, the consideration is based on what’s available to consumers and people in the industry,” says Christine Kamine, a WSET account development manager. This is truer still for the tasting portion of the educator’s courses. “In Thailand, where we have providers, getting White Zinfandel from California or an oaky California Chardonnay is going to be much easier than finding Seneca Lake Riesling. A lot of it is just a practical decision.”

Indeed, much of the tale of California and American wine is just that: practicality. None can argue against the state holding many, if not all of the aces, when it comes to leading the viticultural way on home soil and abroad. But if there’s one thing we should continue to remind ourselves of, it’s that for over half a century, California wineries of all sizes and quality focuses have played that hand so well. And not just to the benefit of themselves.

When Mick Jagger sang, “Thank you for your wine, California” on the 1972 Rolling Stones classic “Sweet Virginia,” he might as well have been speaking on behalf of both the American wine drinking public and its industry as a whole.