Last Tuesday, I didn’t expect to be using a calculator at Basin and Range Winery. I expected to be using a pitchfork.

After five minutes of noisy grape crushing at the winery’s downtown HQ in Reno, Nevada, everything had changed. The grapes destined for rosé were a deep purple hue — more like royal purple than anything close to pink — and suddenly the machinery stopped. We immediately had to switch gears.

I’d come to the “Biggest Little City” to help crush the first vintage at one of Nevada’s newest wineries. Until recently, outdated laws made producing wine in the Silver State nearly impossible, despite booming beer and spirits segments across Nevada. In the tiny urban winery that Basin and Range shares with two other small producers, winemakers Wade Johnston and Joe Bernando were adjusting their expectations, calculations, and methods on the fly.

While my experience happened at a brand-new winery, changing course mid-harvest (or even mid-fermentation) isn’t restricted to winemaking newbies. Each year, winemaking events from heat waves to forest fires can force winemakers to change course suddenly or even abandon ship.

For Johnston and the team, the color of the juice alone was too much to inspire a rosé, and a red wine quickly became the option. Away went the stainless steel tanks and out came open-topped bins for red wine fermentation. With juice already pressed and forklifts at the ready, the team went back to the drawing board with calculators, test tubes, and a whole lot of questions.

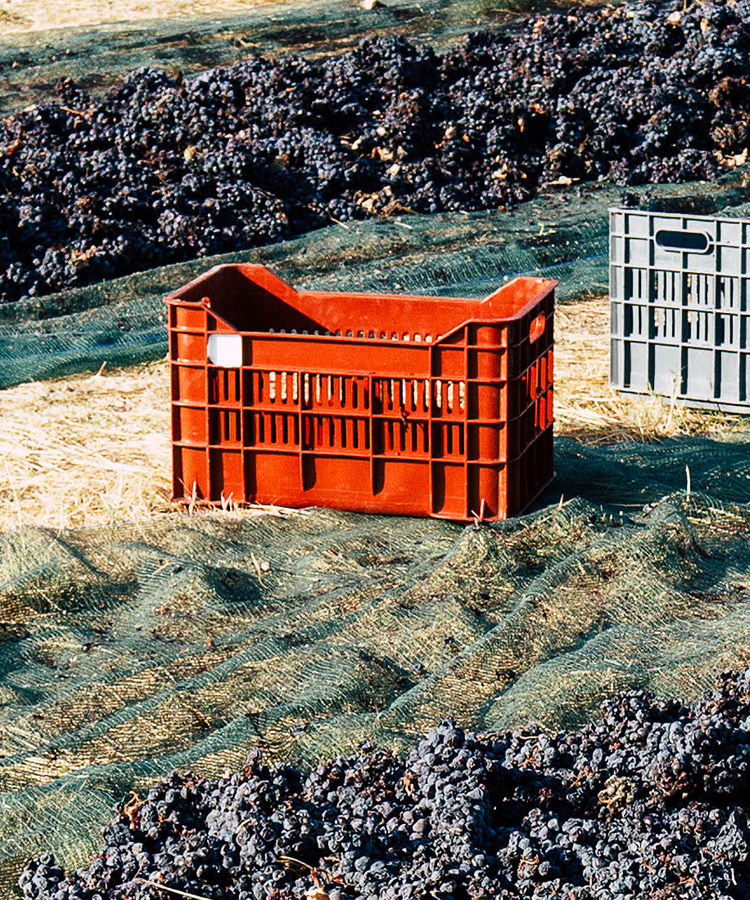

Winemaking is a business filled with variables . Do you leave the grapes on the skins? Add yeast? Add water? Sometimes a single heatwave makes grapes too ripe for a crisp rosé, long before color is a question. During other seasons, grapes gone raisin dramatically change the intended flavor of a wine.

In the vineyard, fire is another major player. When forest fires ravage the West Coast, their smoke doesn’t simply disappear when the flames go out. Often, it lingers for weeks in the valleys that double as wine-growing regions, eventually seeping into the grape skins and marrying the flavors of wine with campfire smoke. Because the smokey smells and flavors are concentrated in the grape skins, red grapes become unsuitable for red wines, leading to a wealth of surprise rosés, or forcing winemakers to dump tons (yes, tons) of grapes they’ve likely already paid for into compost piles.

In the cellar (when everything is going seemingly to plan) fermentations can suddenly stop, leaving off-dry or dessert wines where winemakers anticipated a dry wine. Sometimes, the solution is as simple as moving barrels into the sun, were heat wakes up sleepy yeast cells and gets them back into fermentation mode. In other instances, the options become making dessert wine or using a Hail Mary cocktail of yeast, enzymes and nutrients with flavor-altering potential to jumpstart the stuck fermentation — not an easy choice for most winemakers.

On the mechanical side, the heavy electrical needs of coolers, tanks, and machinery can often leave wineries in a bind.

At Basin and Range, for example, a huge steel tank used for cooling white wines wasn’t near a factory-sized outlet. That changed another plan from simply filling the tank to completely flipping the winery layout. It might seem silly, but small things like the number, size, and placement of electrical outlets, drains, and doors have the potential to change how wine is made in a season, and how easy it is to make said wine.

From Mother Nature to three-pronged outlets, the elements required to make good wine are anything but simple, even if the fermentation process seems easy to grasp. Luckily, there’s a fix for almost any ailment the wine might have, though it often comes in the form of powdered acids or chemicals we’d rather not think about in our food products. Most winemakers I’ve spoken with, including the Basin and Range team, say one ingredient is really important going into harvest: hope.

Today, the Basin and Range Frontenac is fermenting away proudly with its brilliantly purple hue. Only time will tell if its route to the glass is simple, or filled with twists, turns, and Hail Mary additives. Fingers crossed.