This October, VinePair is celebrating our second annual American Beer Month. From beer style basics to unexpected trends (pickle beer, anyone?), to historical deep dives and new developments in package design, expect an exploration of all that’s happening in breweries and taprooms across the United States all month long.

The year is 1986, and Halloween is fast approaching. Whatever will you wear? Don’t worry, The Los Angeles Times has a Fright Night costume dispatch that should help you hone in on the season’s spookiest, sexiest get-up.

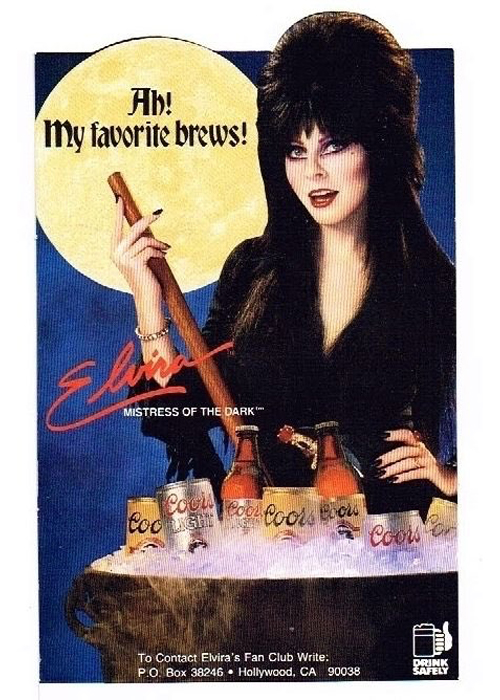

“Carmen Miranda is in, Playboy bunnies are out, and people are scouring the city for Gumby attire. Belly dancers are hot, and Cleopatras, too. But topping them all in popularity is curvaceous cult heroine Elvira, currently of Coors beer commercial fame.”

The Elvira, she of the pitch-black mane and pale-moonlight bosom? Of Coors beer commercial fame? In this day and age, it’s hard to believe, or even remember. But for a handful of years toward the end of last century, the Mistress of the Dark was all over the airwaves pitching a new light beer from the mid-size Colorado brewery, which was at that point just starting its national push after decades of distribution restricted to the Western U.S.

Elvira’s Halloween Coors spots were instant classics, and gave the then-new Silver Bullet an enviable hold on the adult-ifying October holiday, which had previously been the province of candy companies catering to trick-or-treating kids. But as good as they were, they wouldn’t last. After less than a decade, the two parted ways. It was a blow to the brewery’s marketing department, then struggling to compete with the high-dollar heavyweights in Milwaukee and St. Louis. And it was baffling to the Queen of Halloween herself.

“All of a sudden it was like, ‘Oh, we don’t understand these [ads] anymore,’ and ‘Oh, we’re not gonna make a [TV] commercial, we’re just gonna have you do a voiceover,’” Cassandra Peterson, the entertainer who created and has played the Elvira character for over four decades, tells VinePair. “It was like, What?”

Why didn’t Coors keep making black, beer-selling magic with the Mistress of the Dark? It’s a spook-tacular war story from the ‘80s light-beer battlefields, a cautionary tale of the collision between mainstream beer marketing, well-funded Christian conservatives, and accusations of occult behavior. And, of course: cleavage. But before Elvira’s “gravity-defying bosom” enters the frame, we’ve got a Beerwolf to meet.

Of Light Beer Wars and Silver Bullets

Years before Elvira ever set foot on a Coors Light commercial soundstage, the Colorado brewery had plenty to be afraid of. After decades of nearly unchallenged dominance in the American West, by the mid-‘70s, Coors had encountered new bogeymen in its backyard. “Smelling blood,” wrote author Dan Baum in his 2001 history of the company and its eponymous family, “Citizen Coors,” Anheuser-Busch “was coming after Coors in California with discounts, price promotions, and a bottomless-pockets advertising blitz.” And from the Midwest, Miller was menacing the Colorado brewer’s territory, too, bludgeoning the Banquet Beer with its not-so-secret weapon, Miller Lite. “Miller, which had sold twice as much beer as Coors in 1977 and was already the country’s number-two brewery, attributed almost all of its growth to Miller Lite,” wrote Baum.

The situation was all the more doom-and-gloom in Golden because Coors (which, despite going public in 1975 remained firmly under the company’s powerful, family-controlled board, led by Bill Coors, chairman, and Joe Coors, president) was almost fatally late to the light beer game. By the time the Coors elders accepted the inevitability of light beer it was 1978, and the fledgling Silver Bullet brand had a lot of catching up to do. “Coors seemed to be the brand that was competing against Miller [Lite] and [Budweiser] for all the key holidays,” says Gary Naifeh, a career marketer who served as the Coors Light brand director in the early ‘80s. “Coors Light was, to some degree, playing second fiddle.” At the time, the Colorado brewer was only distributed in 11 states, while Miller and Anheuser-Busch products were available nationally. And when St. Louis marched Bud Light into Coors country in 1982 as part of the brand’s national rollout, Naifeh found the bloody battle for light beer supremacy knocking on his door.

Then, as now, holidays were key “occasions” in the American beer business — an opportunity to move cases and kegs with splashy ads, clever in-store promotions, and limited-time offers. But: “The national holidays were just owned by Miller” and Anheuser-Busch, Naifeh tells VinePair. With their national distribution, spectacular scale, and marketing savvy — Miller’s honed at then-owner Phillip-Morris; A-B’s bought with mountains of dough — the bigs were gobbling up primetime airwaves, appointment-viewing sports, and holiday specials across the country. But Halloween, long considered child’s play, was still up for grabs.

“Halloween was building steam, it was becoming a more adult holiday,” says Peterson, crediting both the gay community at large, and the 1984 national syndication of her show, “Movie Macabre,” for that shift. (MTV seemed to agree: In 1986, it tapped the Mistress of the Dark to anchor its Halloween special from Salem, Mass.) The outgunned marketing team in Golden saw an opportunity the big brewers had overlooked. “Halloween was not a big holiday in the beer business, and Coors was looking to find a way that it could own a particular holiday,” recalls Naifeh. “I thought, gee, I really like Halloween, and we have adult Halloween parties in my house. Maybe it could be a really big adult holiday.”

Coors Light’s first crack at inserting itself into the trick-or-treat discourse came in 1983, when it introduced the Beerwolf, a howling werewolf that could only be brought to heel by — you guessed it — Silver Bullets. What happened? Peterson remembers the campaign as a flop in her new bestselling memoir, “Yours Cruelly, Elvira”: “[T]he cheesy-looking hairball didn’t quite accomplish what [Coors had] hoped for.” Naifeh says the opposite: The Beerwolf was a smashing success, once the marketers got the blessing of the notoriously staid Coors family brass. “It was such a big hit with the public [and] when I introduced that stuff to the wholesalers at our national convention, there were people literally standing up on chairs and clapping,” he tells VinePair.

Regardless, by 1986, Coors Light’s marketing department was looking for its next Halloween hit. “There’s a saying that people don’t get tired of your commercials, you get tired of your commercials,” says Rob Klugman, who was vice president of marketing at Coors during the Elvira era. (He has since left the firm.) The Beerwolf’s successor would have to be bold, hip, and TV-ready if the Colorado brewer was going to keep pace with the bigs. From Los Angeles, the Mistress of the Dark beckoned.

The Ads

Elvira’s witchy star was on the rise by the time Coors came knocking in 1985 thanks to passionate local fans in L.A. and the aforementioned syndication deal. (A feature film, “Elvira: Mistress of the Dark,” would follow in 1988.) But Peterson nevertheless remembers the beer brand’s pitch as a pivotal step for the character: a national ad campaign, with all the exposure and money that it entailed. “This was the most lucrative source of income we’d had since the character began,” she writes in “Yours Cruelly, Elvira.” (The chapter, aptly, is titled “Boobs ‘n’ Beer.”)

“I had a freaking blast doing” the first commercial, Peterson tells VinePair. Airing in the run-up to Halloween 1986, the 30-second spot‘s concept was cooked up by Coors’ creative team and Chicago ad agency Foote, Cone & Belding, but the horror host brought it to life with her signature valley-girl-meets-goth lilt and striking figure. “Here I am, stocking up for Halloween — got my stakes, got my ribs,” she says, gesturing toward a shopping cart full of wooden spikes and human bones. “When I ask the stock boy where the Coors Light is stacked, he points me to the Coors and Coors Light Halloween display, and I’m on it!” Then Peterson strikes a pose next to a life-size cardboard standee of herself to amplify the punchline: “Whoa, it’s like deja vu!”

Both the ad and the standee (which we’ll come back to) went over big. According to Baum, Elvira’s “raunchy and hugely popular Halloween campaign” comprised part of “a fresh wind of positive change [that] blew through the brewery” in the mid-‘80s, along with a long-delayed embrace of computers, and plans for a new $70 million facility in Virginia that would help take the company national.

(For what it’s worth, Klugman offered a less sweeping, albeit still positive, assessment of Elvira’s import to Coors. “Obviously if we did [the Elvira Halloween campaign] for five years or so, we were happy with it, but this was a campaign that ran for three or four weeks a year. I don’t know that I’d be comfortable saying it had much significance beyond that.”)

But before that first commercial ever hit the air, Coors’ marketers had to get buy-in from the board of directors — which meant they had to get buy-in from Bill and Joe Coors themselves. According to Naifeh, Bill Coors had personally and enthusiastically greenlit the early Beerwolf spots, which featured the beercanis lupus chatting up a few bathing-suited women. But Elvira, with her occult aura and — in Klugman’s words — “what must have been a very, very good push-up bra,” was another story. So after getting storyboards together, the department cut a test reel with Peterson to present to the board.

As the former vice president of marketing recalls in a recent phone interview, the presentation was hardly smooth sailing. “They had two problems: One was that Elvira, whatever she was, vampire or whatever, this was not an acceptable Christian concept.” Klugman sighs. “And second was her cleavage.” To Peterson, the idea that her boobs would jeopardize the campaign is still patently absurd — it’s literally and figuratively central to the Elvira character, a trait she likens to Superman’s “S” mark. But to get the deal done, she collaborated with the Silver Bullet marketers about how much cleavage she’d show in the spots, with an eye toward winning approval from the conservative Coors elders. The result: “I’m showing about as much cleavage as a teenage boy,” she says of the ads, laughing exasperatedly. “I had my hair pulled forward, and I even put tape on my chest so that I could stick my hair to it. … I mean, how crazy, right? They’re selling beer, not Pampers!”

Crazy or not, the modesty gambit worked, and Elvira’s Coors partnership got the all-important Coors family green light. The Elvira spots ran alongside a full-court-press retail activation that included massive case mountains of Coors and Coors Light and a reported 150,000 life-size Elvira standees, carried forth to retailers by its fired-up distributing partners. The standees were a huge competitive edge for Coors, Naifeh remembers. “When you can walk in with something like Elvira, who obviously is known outside the beer community … I mean, the people that were the buyers at the Kroger’s and the Safeways, they knew Elvira. So when you can give a retailer something that [they think] is really cool, you just bought yourself a place in their establishment to feature your products.”

Covered-up cleavage aside, Peterson was pleased with the cut-outs. “They stopped in-store traffic flow faster than a spilled case of Mrs. Butterworth’s pancake syrup on aisle thirteen,” she writes in her memoir. And customers loved them, too — perhaps too much. Klugman told The L.A. Times in 1986 that the company was having trouble getting them to retailers, because people kept walking off with them. (“I’m afraid to find out what people are doing with them,” another Coors executive told the paper.)

Everything was coming up Elvira, and Halloween was the Silver Bullet’s for the owning. But even as the tax reports rolled back to Golden showing Mistress of the Dark-induced sales upticks, trouble was brewing in the Coors family cauldron.

Ditching “the Demon”

VinePair was not able to verify when, exactly, things started going south between Elvira and the Coors Brewing Company, and contemporary reporting proves deficient on this front. Peterson pegs the souring of relations to 1988, following Procter & Gamble’s bizarre, unfounded Satanism scandal a few years earlier. Naifeh was foggy on the exact year, and so was Klugman. Molson Coors declined to make Peter Coors (who was president of the company’s brewing division in the Elvira years, and chairs Molson Coors’ board of directors to this day) or anyone else from the company available for an interview.

Regardless of the exact date, at some point in the late ‘80s, the brewer backed away from Peterson’s character. Despite the successful Halloween campaigns, or maybe because of them, Elvira had become unpalatable to one or several Coors family members. Baum lays the blame at the feet of born-again Christian Jeff Coors. “Jeff could barely look at the Halloween promotions using ‘Elvira, Mistress of the Dark,’” he wrote in “Citizen Coors.” “They stirred in him a powerful revulsion, even fear.” Between that and the P&G saga then playing out in the headlines (or both), the Silver Bullet’s affiliation with Elvira proved too unholy for the firm’s executives.

(In a zany turn, Baum reported that the Coors marketers even tried to devise a cardboard modesty panel to send out to distributors to affix to the standees already in circulation, in order to save the company’s Halloween that year. Naifeh says that never happened, and Klugman doesn’t remember. But Peterson insists it went down. “I had a big argument with them,” over the panels, she says. “There was nothing to cover. I don’t know if they were gonna knit turtleneck sweaters and send them out to everybody, because you [already] couldn’t see anything!”)

Whatever the year, Peterson and Naifeh both remember the brand stopping down on the commercials for at least one season, maybe two, then trying to start them back up again. What contemporary media remains from that era seems to confirm that timeline: On YouTube there are Elvira spots with burned-in copyright dates from 1991 and even 1994. But the comeback was not to last. The brewer bailed on the buxom host, and the latter says it was not a mutual decision. “The reports of Coors and Elvira’s amicable parting of the ways were grossly exaggerated,” Peterson writes in “Yours Cruelly.” Here again, the record is foggy, and most signs point to a Coors family member finally killing the campaign. But Peterson says it wasn’t Jeff, but Joe Coors, who shut down the spooktacular spots for good. This would track: While Jeff was technically Coors’ parent company’s president at the time, his father, Joseph, a major Republican donor who wrote the check that launched the right-wing Heritage Foundation, was involved in the firm’s operations until the late ‘80s, and remained on its board until retiring in 2000.

Peterson wasn’t personally in the room for his pivotal ruling, but she’s pretty sure Joe ended Elvira’s run around 1995. She says her counterparts within the company, at some point toward the decade’s end, brought a cardboard cutout to the elder Coors for review — and he saw Satan’s fingerprints all over it. “They said that they took the latest standee into Joseph Coors, to see what he thought, and he said — and I remember their words like it was yesterday — ‘I see demons there!’”

From then on, according to Peterson, Coors’ marketers tried to dial the campaign back to voice-over and radio, to keep the Mistress of the Dark’s slinky, salacious likeness off screen (and therefore, out of eyeshot of any Coorses concerned with eternal damnation.) But that idea frustrated the horror host, who by then had come into her own as a bona fide B-list star with a national cult following. Worried that when the watered-down campaign flopped she’d be blamed, Peterson and her team decided to walk.

It was a bitter pill, all the more so because she’d had so much fun on the campaign — and because she’d adjusted her character’s chesty image to accommodate the Coors family’s modesty requirements. But never again. “After Coors, I drew the line,” she says. “I said to myself, my character needs to look like this all the time. I’m not going to put panels over my boobs, I’m not gonna try to cover them up.”

Coda

If this story were written in 2020, it would end right there. But with the publication of “Yours Cruelly, Elvira” in September 2021, Peterson dropped a bombshell on her still-loyal legions of fans: For the past two decades, she’s been romantically involved with a woman. Elvira, Queen of Halloween and longtime gay icon, is a member of the queer community herself.

This begs the question: Did the Coors family’s well-documented track record of funding right-wing organizations that worked to block protections and marriage rights for LGBTQ+ Americans factor into the breakdown between brewery and horror host? At the very least, it would have been impossible to ignore, posits Allyson Brantley, Ph.D. The professor of history at California’s University of La Verne authored “Brewing a Boycott,” a historical account of the three-decade collective action waged by labor organizers, Chicano and Black activists, and the LGBTQ+ community in an attempt to force the Colorado brewer to improve its hiring practices and politics. “At first the boycott began as a shop-floor conflict … in the ‘50s and ‘60s, but in the early ‘70s, Joe Coors himself became more public in his politics,” says Brantley.

Around that same time, the labor wing of the anti-Coors coalition drew the queer community into the fight with a grim detail on Coors’ hiring practices: a polygraph test that included questions about prospective employees’ sexual preferences. “A lot of employees said the polygraph test asked problematic and invasive questions,” says Brantley, noting that the general practice of requiring lie-detector tests for employment was not itself uncommon at the time. As the late Baum put it in a May 2000 interview with C-SPAN, “This was a company that used to run lie-detector tests to run the homosexuals out.”

With that, queer organizations like Bay Area Gay Liberation, the Stonewall Democratic Club, as well as contemporary gay leaders like San Francisco mayor Harvey Milk, joined the fight against Coors. Queer consumers proved to be one of the boycott’s staunchest wings until the AIDS epidemic ravaged the community in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, Brantley adds.

(In an emailed statement to VinePair, Molson Coors spokesperson Marty Maloney said: “Molson Coors has a long history of advocating for the rights of the LGTBQ+ community because that’s what we believe is right. That was true more than 20 years ago when Coors Brewing became one of the first companies to extend health benefits to the partners of LGTBQ+ employees, and it remains true now.” He did not dispute Brantley’s description of the lie detector tests, which Coors reportedly began phasing out in 1986 after Congress began exploring bills to prohibit them from companies’ hiring processes.)

VinePair asked Peterson whether she was aware of the Coors family’s posture toward the gay community, and whether it factored into her decision to work with the company, particularly given the revelations of her memoir. “In the beginning, I had no idea, didn’t even think about it,” she says. But in the intervening years between her first and second wave of Coors spots, she continues, “I had discovered that the gay community had boycotted them for their many right-wing causes.” When Coors came back around to restart the Halloween campaign, the Mistress of the Dark was ready.

“I met with some of their marketing team, and I actually believe I helped make a bridge to some gay activists in the community, to talk about that with Coors to help resolve the issues that the gay community wanted resolved,” says Peterson. “I used that as one of my bargaining chips when we went back to Coors because then, I had a little power.”

Whether this righted any of Coors’ wrongs in the LGBTQ+ community is up for debate, says Brantley. The company began pouring money into gay organizations, either to clean up its image in the eyes of queer drinkers, or because the company’s new, non-family leadership believed it was “right,” or both. But Coors family members remained powerful players in right-wing politics. As recently as 2004, the comparatively forward-thinking Peter Coors — who, even according to the mostly unsparing Baum, was friendly with gay and lesbian customers — ran unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate in Colorado on a platform that included support for a constitutional amendment to ban gay marriage. (He supported civil unions for gays and lesbians; Coors Brewing’s then-CEO disavowed his chairman’s politics even so.) Still, it seems like a net positive if the Mistress of the Dark was able to move the Coors Brewing Company toward some form of reconciliation with the gay community — even if it wasn’t quite a Silver Bullet.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!