Jeremy Kosmicki pulled a single hop off of an 18-foot bine and rubbed it between his cupped hands, releasing the hop’s aromas shortly before he brought his hands to his face and deeply inhaled. Kosmicki, the brewmaster at Founders Brewing, paused, then inhaled again, comparing the smell of the Hopsteiner branded hop to the countless other hops he had done the same thing to throughout the day.

It’s easy to get lost in the moment meandering through a Yakima, Washington hop field during the September harvest season. Evenly spread rows blend into one patchwork quilt that pushes up against the edge of the Cascade Mountains. The hills are a dry, mousy brown. The quiet roads are dusty, with an occasional cluster of leaves and hops in the middle of the lane, dropped off a passing truck and forgotten among the mesmerizing lines of plants waiting for harvest.

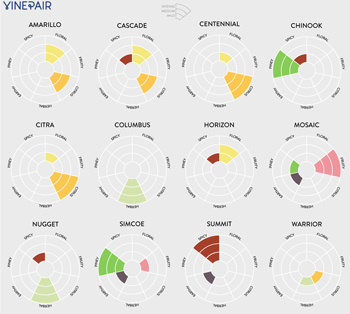

But the homogeny is misleading. The term hops doesn’t even start to breach the distinctive nuances that brewers travel to central Washington to find. Where to start? There are more than 170 hop varieties and the list is only growing. Some are public varieties that anyone can commercially grow. Some are proprietary and can only be grown by certain companies. Still others, like the one Kosmicki picked and sniffed on the Hopsteiner farm, are still in development and don’t even have a name yet, identified solely by a string of letters and numbers.

To be honest, I’m no hop head. I’ll crush every new beer I see with abandon, but selecting hops by the farm, brand, and field was a foreign idea before I toured the farms alongside the crew from Founders. The idea that the prosperity of an entire farm can rest on a uniquely branded agricultural product wasn’t on my radar — the flavor of the beer rested solely on the brewers in my mind. It sounds ignorant, but when’s the last time you thought of beer as something born from a proprietary agricultural product while downing a local brew in a dingy beer bar?

It didn’t take me long, however, to quickly grasp that branded hops are big agricultural business crucial to craft beer development, and Yakima is the main office.

Around 75 percent of the total acreage devoted to hops in the United States is grown in the Yakima Valley. International corporations and family farms butt up against each other to provide more than 77 percent of the total United States hop yield, two-thirds of which is shipped around the world. And while the big public varieties are ubiquitous, nearly everyone is searching for the next big taste the newest privately developed hop will provide — if there is a next big taste at all that hasn’t already been found in an existing hop brand.

“Emerald came out and it was like grapefruit in your face and citrus — that was a good thing,” Kosmicki told me at a brewers dinner put on by Hopsteiner. He was relaxed, in a white button-down shirt, his long black hair pushed back behind his shoulders. The experimental varieties he smelled earlier in the day were good but not distinct enough. “When Citra came out, it was really lemony, then Mosaic came out and it was tropical fruit, and peach, and blueberries, and things like pineapple and pine.”

“I don’t doubt that there are still more flavors to dominate and lead the way,” he said, “but it’s just hard for me to imagine it until I come across it.”

The relatively small inner circle of people who truly understand branded hops is populated primarily by brewers and beer nerds who can geek out about alpha acids and total oils. They are the people who know what it feels like to walk the fields, crush and warm hops in their hands, and then try to scrub off the sticky green residue the crushed hops leave. To these people, branded hops, and new brands in development, are everything.

“Will there be a tipping point where people just can’t use them anymore and they’re priced out? Yeah, maybe,” Kosmicki said. “It depends what happens with the industry, but I feel right now we rely on these new hop varieties. That’s what brewers want, that’s what consumers are into.”

He’s not extrapolating. The craft beer industry is booming, both in America and abroad. And in case you haven’t walked into a bar or a grocery store in the past 10 years, American craft is largely centered around IPA, which disproportionately relies on hops and hop farmers compared to styles like lagers and Pilsners.

“They’re monitoring what we want from our standpoint,” Dave Engbers, one of Founders’ co-founders, told me after a tour with the owner of CLS Farms. “Then they have to plan for what the future is going to be. They’re always looking for the next big hop.”

It’s hard to exaggerate the importance of branded hops. Craft IPA without a distinct hop like Mosaic, Citra or some blend of branded hops is like New York City without the Empire State Building. Branded hops create an identity, and entire beer lines, like Founders’ Azacca IPA with Azacca hops from Roy Farms, are formed around proprietary hops that spent years in research and development.

As Engbers said, though, everyone’s looking for the next big hop. But with 170-plus varieties with flavors from blueberry to pine to citrus, what can follow?

“Right now it just seems like everything is sort of in the vein of everything that’s already been done already,” Kosmicki said. He has no idea what could be next primarily because he hasn’t found it yet.

“I would love to have a hop that is like chocolate-covered strawberries or something, I don’t know,” he (maybe) joked. “But how do you make that? We have probably not even scratched the tip of it all, it’s just hard for me to fathom (what’s next) without experiencing it.”

Earlier that day, I toured CLS Farms with Kosmicki, Engbers, Founders brewer Dave Powell, vice president of wholesale distribution Michael Bell and social media specialist Steve Cummings. At CLS, a portion of the fields were devoted to common hops. At Roy Farms, the main focus was on their hop brands, and at Hopsteiner, an experimental strain that has been in development since 2009 was almost ready to be named.

No one, as far as I could tell, was working on anything drastically different from what has been done before — and that’s OK for the average consumer.

“I think at this point, from a consumer standpoint, you’ve just got to make something that is pleasing to their palate and let them dig into it at their leisure,” Kosmicki said. “The normal person at home drinking Mosaic isn’t thinking, ‘Oh, I get hints of blueberry and peach in there.’”

Even so, people are becoming more discerning eaters and drinkers. Call them hipsters, foodies, privileged, or whatever you want, but there is a growing number of people who care about the flavor nuances in their food and drink. There’s also a seemingly endless amount of craft beer to satisfy the drive for nuanced flavors. More than 24 million barrels of craft beer were produced in the United States in 2015, according to the Brewers Association, 99 percent of which are independent microbreweries, brewpubs and regional breweries.

Numbers and end consumers seem so far away in the hop fields of Yakima Valley, though. Still, craft beer needs branded hops in order to keep coming out with new stuff. Hop growers need branded hops to drive their business. As for general consumers, well, general consumers aren’t thinking about 18-foot bines and sticky hop cones, but that doesn’t mean their taste buds aren’t grateful.