Push alerts are the scourge of our #mobilefirst existence, so it makes sense that Megan Greenwell had turned them off for all her most used apps. It also makes sense that Venmo, the ubiquitous platform that allows strangers to seamlessly transfer one another funds by phone, was not one of those apps.

After all, who walks the earth expecting strangers to simultaneously begin sending them funds with little to no warning? In this economy?! And yet, one fateful late-October afternoon last year, that’s exactly what happened to the editor of Wired, who had helmed the sports blog Deadspin for 18 months before resigning in protest of what she saw as improper editorial meddling by the executives running the site’s parent company.

“All of a sudden like my phone was like too hot to touch because of all the Venmos coming in,” Greenwell told me in a recent phone interview. The money wasn’t for her, not all of it at least. In fall 2019, 20 of the editor’s former Deadspin colleagues began walking off the job in a principled stand against the firing of one of their own, and the site’s fans (who included millions of regular readers per month and many NYC media insiders) wanted to show their support. Greenwell had stepped up as a digital bagwoman on Twitter, posting her Venmo handle and offering to run point on disbursement of any funds collected.

And lo, did the funds roll in. To buy the erstwhile Deadspinners drinks, strangers on the internet ultimately pooled together a “healthy five figures,” says Greenwell. (This went to more than drinks; we’ll get to that in a moment.) “I was like, ‘Holy fuck, I have to figure out how to turn off my notifications!’”

‘In lieu of a better safety net’

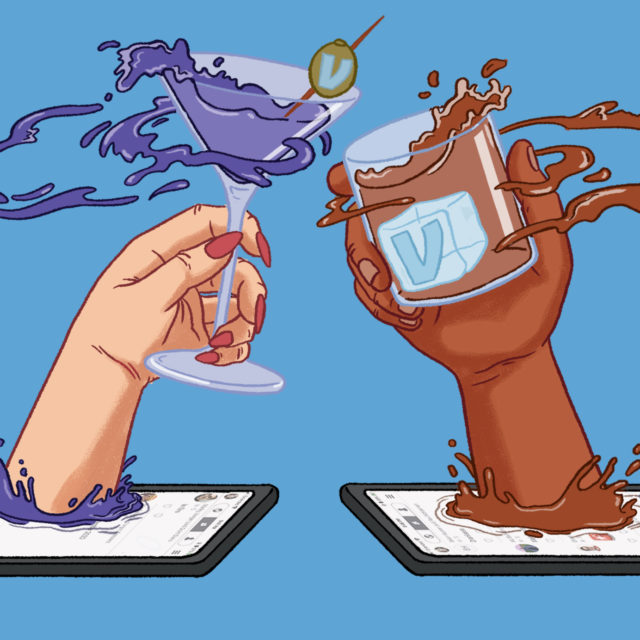

Such is the power and majesty of the “bar tab Venmo,” a digital-age rite borne of journalistic tribalism, smartphone connectivity, and the excruciating death shudders of an ever-collapsing American media ecosystem. It’s a fairly simple exercise: When journalists find themselves out of work, other journalists — plus rank-and-file subscribers, fans of a free press, and so forth — toss a few bucks into a digital bucket as consolation beer money for the newly unemployed.

Unfortunately, layoffs have been a nearly omnipresent specter in the media business for the entire decade I’ve been in it. (This story, in fact, is expanding on an essay I wrote for my drinking culture newsletter after being laid off, for the first time, from a media gig of my own. Fun!) In that time, as shop after shop has shed writers and editors, hard-nosed reporters and soft-handed listicle jockeys, the bar tab Venmo routine has become a bit of a funeral rite.

(Apparently this is a thing that people also did with former staffers of failed Democratic presidential campaigns, which is different and honestly a little weird to me in ways that I can’t quite put my finger on right now. Anyway!)

Given how often journalists get laid off, it’s impossible to say how many of these booze-focused fundraisers have hit the timeline since Venmo was created in 2009. But in the past few years, as the digital-media balloon has deflated in an atmosphere of impossible growth goals, video pivots, and impatient, inept venture-capitalism and private-equity opportunism, they’ve gotten bigger. Due to the site’s stature and its writers’ popularity, the drive for former Deadspinners was arguably the highest-profile of the bunch. The last year and a half alone seen has similar ad-hoc efforts for journalists at BuzzFeed News, Sports Illustrated, The New York Times en Espanol, Outside Magazine … and on and on.

“I’ve spent a lot of time over the past four years or so specifically … donating to bar tab Venmos,” says Maya Kosoff, a freelance writer and editor who, back in the Before Times, wrote movingly for GEN on “the human toll of the 2019 media apocalypse” that put 3,000 journalists out of work. (Smash cut to 2020 and that number looks downright adorable next to the toll taken by pandemic-related media layoffs, which The New York Times ballparked at 36,000 back in April. And uh, folks, things have not gotten better since April!)

“It feels like you’re trying to help your fellow peers get back on their feet at a time when there’s complete instability in the industry, and no guarantee that you’re gonna find another staff job in journalism,” she added. Bar tab Venmo “is kind of in lieu of there being like a better safety net — for reporters, writers, editors, and freelancers.”

“I don’t know where I first saw people doing this,” says Amanda Mull, a staff writer for The Atlantic whose tweet about the Deadspin walkout was among those that prompted Greenwell to offer up her Venmo handle last fall. “Maybe it was an early round of BuzzFeed layoffs? I saw people doing it, so I sent some money. It seemed like just a nice thing to do, people who are losing their jobs or who are in an unstable employment situation.”

Mutual Aid in the Modern Era

Speaking of which: As the coronavirus pandemic continues its literal and figurative death march through the American economy, rolling layoffs and gobsmacking unemployment numbers have become a de rigeur part of the national discourse. There are a lot more workers (both in the media and beyond) in unstable employment situations than ever before.

As such, new conversation has sprung forth about the shortcomings of America’s dismal system of meat-grinder capitalism and what average folks — buried in student loan, perpetually renting, and/or clinging to garbage jobs they hate because the bad health benefits they get are still better than the obscenely expensive alternatives in our cartoonishly corrupt privatized healthcare industry — can do to help each other survive. Like, beyond buying each other drinks, I mean.

Workers, neighbors, marginalized groups, and more have been passing the hat to help their own cover the costs of sickness, death, and bad luck for centuries. That’s neither new (it was a staple of 19th-century fraternal lodges), nor particularly mainstream, in the United States at least. But things are shifting, according to Max Haiven, an author and professor at Lakehead University in Ontario, Canada. Rank-and-file attitudes toward mutual aid were “changing already very quickly before the pandemic, [and they’re] changing even faster right now. … What we’ve actually begun to see is that since Covid, a lot of workers who previously were not unionized are now taking forms of collective action.”

At the very least, people seem more aware of the idea. Google Trends indicates that interest in the phrase “mutual aid” has been higher than normal for virtually the entire duration of the coronavirus pandemic. That tool also suggests searches spiked directly after a police officer killed George Floyd in the street this past spring, which makes sense because American capitalism and American racism are “different” in the sense that Bud Light and Miller Lite are “different,” which is to say sort of but also not really.

What’s the connection between neighborhood grocery deliveries and strangers paying each other’s medical bills, and random Twitter avatars throwing beer money at unemployed bloggers? Ah, so glad you asked, my dear rhetorical device!

Drinks Do Not a Union Organize

To Haiven, journalism’s money-for-booze routine isn’t quite a pure expression of solidarity — it’s long on symbol, but short on substance, and is probably predicated a bit too much on journalism’s romanticized “brand” and the popularity of individual outlets and writers to constitute real movement-building action.

On that, all the journalists I spoke with for this story agreed emphatically. “Part of me is a little unsettled by the popularity aspect of it,” says Greenwell. The success or failure of a bar tab Venmo is “not determined by who needs it the most, and it’s not determined by whose circumstances were the worst in terms of their layoff or firing or whatever, it’s determined by popularity on Twitter.”

Kosoff, who received some Venmo dough herself after leaving “new Gawker” over ethical concerns regarding the site’s leadership, echoed that reservation, warning that the practice is potentially exclusionary and even “clique-y” — words more or less incompatible with true solidarity.

Another aspect of bar tab Venmo that makes it more a “solidaristic” behavior than a true form of solidarity is that the stakes are relatively low. With the exception of alcoholics who’d be wracked with delirium tremens in the absence of drink, buying rounds for writers online is not really in the same category as, say, passing the hat to help the family of a union brother slain on the job to cover funeral costs.

And contrary to what you’ve heard, not every journalist unwinds at the end of the day with several glasses of Scotch. “Sending money for booze is a heartwarming gesture and a good expression of love and solidarity for people who have been laid off,” says Hamilton Nolan, a labor reporter for In These Times and a former staffer of the various companies that have owned Deadspin. “But speaking as someone who doesn’t drink, I would suggest that an even better practice would be just donating cash to laid off workers. They can buy their own drinks, or pay the rent.”

Still, Haiven says, if labor activism occurs on a spectrum, with strikes and solidarity actions between different unions or workers organizations on one end, “on the other end of the spectrum are these like small almost seemingly insignificant acts of mutual aid, where people say ‘actually, our fates are connected.’”

“It’s kind of a culture of solidarity that could then turn into the structures of solidarity,” he adds.

Beyond the Bar Tab

Those structures, it should be noted, are already being built both outside media — and within it. After five decades of declining union density in the United States, the digital-media industry was a bright spot in the second half of the 2010s, with a wave of successful union drives, with workers at publications like Vox, New York Magazine, Deadspin, Vice, HuffPost, Salon, and many more organizing themselves to bargain for better conditions and more stability. (Disclosure: I organized at Thrillist, another digital shop that went union in that wave. We won, but it took awhile.)

So while bar tab Venmo is an imperfect vessel for building coalition across the industry, it might act as sort of a gateway drug to more substantive acts of solidarity. For one thing, it’s more for newly activated workers to send fallen coworkers beer money with a few taps on an iPhone, than to, say, write them a check for a portion of their rent, or baby formula, or whatever.

“It’s a perfect way to say like, ‘Hey, I’m thinking about you, when we’re not close enough to say “I’m thinking about you,” so here’s 20 bucks,’” muses Greenwell. Under the guise of sending a round of send-off shots, contributors were able to offer financial support that could cover actual necessities. And it did: The Deadspin fund fueled several outings with Greenwell’s former staff, but also went toward paying months of rent and buying half a dozen laptops for those writers who had previously relied on their company-issue machines. Many of those workers went on to launch Defector, one of several promising new worker-owned media co-ops seeking to reinvent a broken business with good blogs. (Maybe the drinks helped!)

Greenwell imagines mutual aid in an ideal world simply as money doled out to people who need it most, donated by those with common cause who weren’t swayed by individual popularity or, as Kosoff put it, “the stereotype of journalists as miserable sad sacks want to drink together at the bar.” Something less like a bar tab Venmo, and more like the Journalist Furlough Fund.

Launched in late March by Seattle Times reporter Paige Cornwell as a GoFundMe, the JFF is a by-journalists, for-journalists effort to plug the gaping holes in both the media industry’s broken model and the United States’ shredded social safety net. The fundraising target was $60,000, but to date the campaign has raised over $96,000 from journalists, local businesses, public-relations pros … you name it.

Speaking on the phone while coordinating wildfire coverage in Seattle, Cornwell was intent to note two things. First: “I do this independent of my employer,” she says, noting that, though the Seattle Times has been supportive of the effort, it is not a company initiative. (The Times, for what it’s worth, is a partly union newsroom; its digital journalists are currently fighting for their right to join their already-organized colleagues, of which Cornwell is one.)

The second thing Cornwell was adamant about was something every other journalist I interviewed also brought up: The sheer deficiency of crowdfunded mutual aid, even $100,000 of it, when compared to the scope of the problem at hand. Even though the JFF is much more explicitly oriented around aid than a bar tab Venmo, it pales in comparison to the broad, systematic dysfunction of the media industry.

“This isn’t a way to make up for [a laid-off journalist’s] loss,” says Cornwell. “It’s for keeping someone from the edge.” As the administrator of the fund, she’s disbursed cash to journalists across the country for daycare tuition fees, medical bills, equipment, and more. The JFF can help some journalists in a pinch, but still, “it’s not enough,” she says.

That doesn’t mean she plans to wind it down anytime soon, though. After surging in the spring, contributions to the fund have slowed, but considering that things are only getting worse in the American media business, she’s hopeful that people will contribute again if they can — if not to “fix” the media, then at least to keep more writers and editors from the meat grinder. “Someone else can figure out how to save journalism as a whole, [the JFF] will just make sure that someone will be able to buy their daughter school supplies,” she quips.

“It’s just so ridiculous that we even have to have those conversations.”

I’ll drink to that. (Please Venmo me.)