Do you like to feel mystified, intimidated, inadequate? Then walk this way! I have a vintage chart to show you.

Down the left hand side there’s a list of regions — you know, California, France, Italy. Ha, just kidding. There are 20 different classifications in California alone, plus another half-dozen in Oregon and Washington. Make sure you know your North Coast from your Central Coast, your Sonoma Zinfandel from your Sonoma Cabernet. Not to mention the differences between Marlborough and Martinborough, or Maipo and Colchagua, or Basilicata and Puglia. Oh, I might have failed to mention the ten different regions that chart-makers have managed to furnish just within Burgundy and Bordeaux.

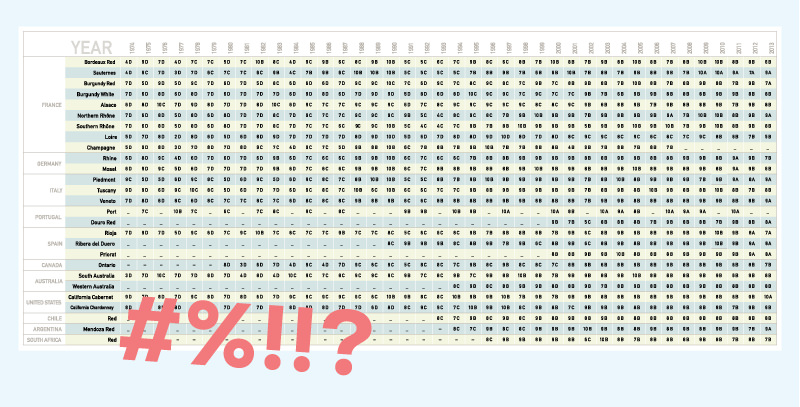

All in all, there are 102 rows to the chart. Each one has 16 columns (each year between 1990 and 2015). Every cell has a different color, corresponding to “maturity,” and also has a “rating” somewhere between 80 and 100. All in all, there are 3,264 data points, and each data point can have one of 198 different states.

Trying to navigate such chart has more in common with learning German irregular verbs than it does with enjoying a lovely glass of vino.

And no one should ever bother.

Because the good news is that vintages are over. They’ve had their day. They might have been useful, once upon a time, before winemaking techniques had advanced to the point at which it’s pretty much unthinkable for a good winemaker to produce a bad wine, no matter what the weather was like that year. But nowadays, you can feel free to bask in blissful ignorance of whether there was an early fall in northern Italy last year, or a particularly hot summer in Chile. Whatever the vintage on the shelves, it’s going to be entirely representative of the wine you’re buying.

People still care about regions and grape varieties, of course, with the standard tilt toward regions in the Old World and varietals in the New World. You might like Sicilian reds, or Oregon Pinots, and that’s great. But the days are long gone when anyone but the ponciest wine snob would get excited or disappointed upon seeing a bottle from a “good year” or a “bad year.”

The reason is that the narrative has changed.

Wine has always been about storytelling, and once upon a time the stories being told were in large part about the weather. Grapes grew in fields, at the mercy of the elements, and their growers hoped for lovely hot summers that would yield lots of ripe, juicy fruit. In a happy coincidence, the years with the highest yields were also the best years in terms of quality, and so there was no problem selling them.

But then science came along, starting at UC Davis in California and soon encompassing the entire planet. Science told farmers exactly when to pick their grapes; it also allowed them to make good wine even in bad years with low yields. The weather still matters a lot to the growers: Higher yields mean more money. But it matters much less to drinkers.

Something much more interesting has taken its place. Stories about the weather are barely stories, they’re small talk. Once you’ve heard one story about a sudden thundershower or an unexpected frost, you’ve heard them all, pretty much. But stories about people will never not be interesting. And so, just as vintages have waned in importance, winemakers have waxed.

It can be hard to remember today, but not that long ago, you barely heard about actual winemakers. The important thing was the brand: the label, the chateau, the piece of land where the wine was grown. Winemaking was an aristocratic vocation; vineyards were passed down through the centuries, and insofar as there were celebrated individuals, they were quite likely to be smooth-talking owners in Savile Row suits who rarely if ever got any precious terroir under their fingernails.

But as the bad vintages in posh regions started getting better, wine lovers started to realize that a lot of the credit for great wine properly belonged to the winemakers. Turns out all you really needed to make good wine was vision and ability and a bunch of grapes to play with. Rather than seeing the wine world as something eternal and unchanging (except for the weather), importers and sommeliers started getting excited about people and places they had previously ignored.

When they visited these new regions, they didn’t arrive with preconceived notions about which plots of land were the best, which brands were the most storied. And there certainly weren’t any chateau-dwelling aristocrats to impress them with the trappings of centuries of tradition and wealth. Instead, there were just the winemakers themselves: often young, very enthusiastic, frequently organic, sometimes even biodynamic. And they were making weird, wonderful, delicious wine.

Now, winemaker intel can replace the intricacies of vintage in that crucial part of the wine conversation where you need a story to go alongside the facts about the geography and grape varieties. And looking at a vintage year becomes a much, much simpler proposition.

Instead of studying a vintage chart, all you need to be able to do is subtract the vintage year from the current year to work out whether the wine has, as they say, “some age on it.” If it’s older, that doesn’t necessarily make it better, but it does often make it more interesting. Insofar as there’s a difference between the 2005 and 2015 vintages of any given wine, most of that difference is going to be due to age, not the difference between the weather in the two years.

So! You can stop feeling that vintage charts are something you should know or care about. The world has moved on, and now we can celebrate individuals instead. Which is much more fun.