Humans have been imbibing wine for thousands of years. We’ve already explored how wine, specifically vitis vinifera, spread around the world through trade, religious missions and colonization. But that story naturally leads to the question of how wine got from one place to another. While it’s relatively easy to carry vine cuttings on long journeys, bringing finished wine with you is a much more difficult task. As we explore the many ways humans transported wine over land and across oceans, we’ll cover over 8,000 years of history and technical accomplishments. If there’s truth to the old cliché that necessity is the mother of invention, then as a species, we’ve shown a serious need to drink wine.

The Basic Challenge

Transporting wine is a tricky task, as your storage vessel needs to accomplish four different goals:

- Air must be kept out of the vessel to prevent oxidation.

- The vessel must be strong enough not to easily break, without being so heavy that it cannot be easily moved (especially when hand labor was the rule).

- In many cases, the vessel needs to be opened and then resealed.

- The vessel itself shouldn’t interact with the wine (though we’ll see that a very large asterisk follows this rule).

In addition to those goals, the vessel needs to be stored in an environment that has a stable temperature. If wine is exposed to heat for too long it will ‘cook’ and lose its flavor.

The Kvevri – Invented In Georgia Circa 6,000 BC

Unlike the rest of the storage devices we’ll talk about, kvevris (also translated as qvevri) were probably not used for transporting wine. Some historians speculate that they were, but it’s not very likely. Why isn’t it likely? They were quite large and they were buried in the ground to ensure climate control sans electricity. While it’s hard to pin specific dates when archeologists take us this far back in history, we can say with certainty that the Ancient Georgians were using these large, beeswax coated, earthenware vessels as early as 6,000 BC.

Unlike the rest of the storage devices we’ll talk about, kvevris (also translated as qvevri) were probably not used for transporting wine. Some historians speculate that they were, but it’s not very likely. Why isn’t it likely? They were quite large and they were buried in the ground to ensure climate control sans electricity. While it’s hard to pin specific dates when archeologists take us this far back in history, we can say with certainty that the Ancient Georgians were using these large, beeswax coated, earthenware vessels as early as 6,000 BC.

So what makes a kvevri so special? Aside from being the oldest storage vessels we’ve discovered to date, they were used in every stage of wine production, from grape crushing to aging. Unfermented grapes, naturally growing in the region, were dumped into a kvevri, which could hold hundreds to thousands of liters of liquid depending on its size. The grapes were then crushed (stems included), the kvevri was buried (to keep the wine at a steady temperature) and primary fermentation commenced. Once the period of primary fermentation was over, the kvevri was covered with a large stone to create an airtight seal. The kvevri was then left undisturbed for up to two years, allowing the wine to undergo malolactic fermentation and a period of aging. What came out at the end was an earthenware-aged wine that was highly tannic. Want a taste for yourself? A few Georgian and Italian wineries have returned to the kvevri method of wine production.

The Amphora – Standardized Clay Containers From The Bronze Age

Amphorae were the ancient world’s standardized way to transport wine, olive oil and other prized liquids. Amphorae came in many sizes, similar to both the bulk transport formats we use today as well as the world’s common wine bottle sizes. These wax-lined (pine and bees wax were common) ceramic containers, invented by the Egyptians, were gradually adopted by nearly all the wine drinking/producing civilizations throughout the Mediterranean and Mesopotamian regions. They reached their peak in usage and standardization in ancient Greece and Rome. They were easy to produce and, importantly, easy to transport. Their shape – round with a tapered bottom, two handles and a long, slim neck – served four purposes:

- The long slim neck reduced the surface area of wine that would be exposed to oxygen.

- The tapered bottom allowed sediment to collect and the amphora itself to be easily buried when cooler, long-term storage was called for.

- They fit well in the ships of the day.

- The handles eased the load of carrying them.

The amphora’s tapered bottom also proved to be useful in keeping its contents from sloshing around during a sea journey. This was accomplished by filling a ship’s hold with sand, and then partially burying each amphora in the sand. Looking at an amphora you can see the similarities to a modern wine bottle, from the long neck, which keeps the wine away from oxygen, to the sediment-collecting concave bottom of most wine bottles, the ‘punt.’

Sealing an amphora was a challenge for all ancient peoples, and the solutions varied over time. An amphora was originally sealed with a clay stopper, but these stoppers allowed a good bit of oxygen to enter the vessel. The Egyptians used materials such as leaves and reeds as seals, both covered in semi-permanent wet-clay. Later the Greeks and Romans experimented with rags, wax and today’s favored stopper, cork. Resin, used as an adhesive, was so important to the Romans that different plants were sought out and prized for the varied flavors they added to the wine.

While the Ancient Greeks, as other civilizations before them, often produced elaborately decorated amphorae, to the Romans these vessels were strictly about moving liquid across the empire as efficiently as possible. Over the course of hundreds of years, Roman manufacturers continuously improved their physical design – the goals being to reduce weight without sacrificing strength and to pack more and more amphorae into the cargo holds of ships. This excerpt from David Stone Potter’s book Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire, shows the massive scope of the Roman ‘logistics’ system:

A year’s supply of 20,000,000 liters oil translates into about 285,714 amphorae, and 100,000,000 liters of wine would require 4,000,000 amphorae.

And that’s just for the city of Rome. The author is quick to note that these are estimates based upon some consumption and population assumptions. Still, these are not unreasonable assumptions: archeologists have estimated that Monte Testaccio, ‘an artificial hill’ in Rome, is composed of 53 million or so broken olive oil amphorae, discarded over the course of 150 – 300 years.

For a long time it was assumed that amphorae were the way the vast majority of wine was shipped over long distances throughout the Roman Empire. More recent discoveries of shipwrecks throughout the Mediterranean have revealed that wine was often transported in a larger container called a dolium. At first the dolia were moved on and off the ships, but by the first century BC ships were bring produced with dolia cemented to the floor. The wrecks of purpose-built ships like this have been discovered with capacities of up to 9,500 gallons of wine – the Roman equivalent of tanker ships. That the dolia were cemented to the floor also helped keep the wine undisturbed during long voyages.

The Move To Oak Barrels In Rome

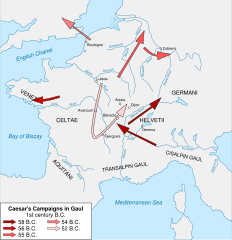

As the Roman empire expanded they met (and conquered) numerous cultures, many of them possessing technologies that they embraced. When the Romans encountered the Gauls they found a people who were transporting beer in wooden barrels, bound together with metal hoops. The Celts are recognized as the inventors of the wooden barrel, but it was through the Gauls that the Romans adopted them. While the Romans were aware that other, earlier civilizations used palm wood barrels to transport wine, until the encounter with the Gauls, amphorae (and dolia) were the transport medium of choice.

As the Romans pushed farther north, they were presented with a new challenge: how to transport wine over long distances of land rather than water. Carrying large amphorae over land, to quench the thirst of vast armies simply wasn’t practical. The wooden barrels provided a solution. As the Romans expanded their empire they also planted vines or expanded and improved existing vineyards they encountered. While these vineyards were at first intended to provide wine for locally garrisoned soldiers, the wine grown in Gaul (modern day France) turned out to be quite popular back in Rome (to the point that the vineyards were torn up for a long period beginning in 92 AD to protect ‘domestic’ producers). This wine made its way back to Rome not in amphorae, but in the wooden barrels that the people of Gaul had been producing to store and transport beer.

Following the lead of the Roman army, merchants quickly adopted wooden barrels in place of amphorae. Wooden barrels are stronger than clay, weigh far less and can be turned on their side and rolled – which was especially helpful to the ancient Roman soldiers marching deeper and deeper into continental Europe.

There was no shortage of trees in Europe, and unlike palm, woods such as fir and oak bend relatively easily. The adoption of barrels was rapid: the military campaigns that Julius Caesar started in Gaul wrapped up in 50 BC; by early the first century AD the Romans had widely adopted barrels. By the third century AD the transition to storing and transporting wine in wooden barrels was virtually complete, ending clay’s 5,500 year period of dominance.

While today we recognize that oak barrel aging is fundamental to the production of many wines (or oak substitutes such as chips in steel barrels), the use of wood was seen as an acceptable compromise for the average Roman, particularly soldiers who were more interested in the intoxicating effect of wine than its taste. Unlike clay, wood barrels are porous, allowing some oxidation to occur. And, as the Romans knew, wood left its mark on wine in terms of flavor and tannins. So while the Romans were aware that different woods each affected wines in their own way, and had observed that wine shipped long distances in barrels often arrived tasting better than when it departed, the adoption of oak was a lucky accident. Over the following centuries, wine drinkers and winemakers realized the positive effects that oak had on wine. Still, the choice to use oak over other woods was heavily influenced by both the abundance of oak trees in Europe and the wood’s tight grain, which makes for a watertight barrel.

Oceans, Rivers, Rails & A Port That Made Great Wines Internationally Famous

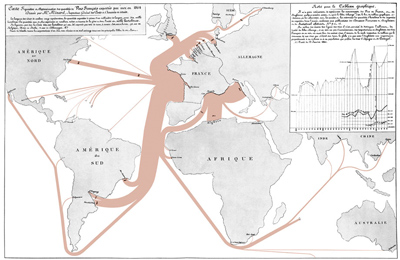

Even in wooden barrels, moving a lot of wine around still was not an easy task. From the Middle Ages on, large barrels called tuns were the standard bulk transport unit in France. Tuns held 950 liters of wine (roughly 250 gallons). Land transport was something you wanted to avoid if possible. And so, in France, and in wine producing countries around the world, a region with easy access to the open sea or navigable rivers held a large advantage over one that did not. In many cases, vast canal networks helped link otherwise inaccessible regions to the river transport network. Whether it was canal or river, the presence of a navigable waterway could vault a region to domestic and even international prominence.

No region benefited from its geographical location more than Bordeaux. When we think of geography when it comes to wine, we’re usually talking about terroir, the soil and climate that define a place. Bordeaux’s geographical advantage was more practical than that. The city straddles the Girronde, the estuary where the Dordogne and Garonne rivers meet the Atlantic ocean. Nearly 2,000 years ago the Romans recognized the value of this location, and that’s why in addition to planting vineyards when they captured the city, they established Bordeaux as the primary European port on their trade route to Britain.

An export market for French wine developed in Britain by the twelfth century, enabled by the typical causes of the age – wars, politics, royal marriages and treaties. The British fell in love with Bordeaux wine, or as they called it, Claret. Trade in wine was so great, and so important relative to other goods, that by the 1300s, ships were categorized by how many ‘tuns’ of wine they could hold. The modern practice of categorizing ships by the ‘gross tonnage’ they can transport can be traced back to the English people’s insatiable thirst for Claret.

Despite all of these technological advances, that vast majority of wine still possessed a short shelf life – less than a year – before oxidation turned it into vinegar. Wines with higher levels of alcohol were the exception to this rule. Taking advantage of alcohol’s ability to extend a wine’s life, by the 1600s, merchants often added brandy to wine that was bound for a long trip at sea. This also led to the rise of fortified wines such as Port, Sherry and Madeira. You can read about the history of Port at Wikipedia. These fortified wines were quite popular in colonial America, as ships headed across the Atlantic (as well as other destinations) often stopped in Portugal’s Madeira Islands, where they would pick up wine for the long journey ahead.

Finally, in the nineteenth and early twentieth century the growth of railroad networks opened up many otherwise inaccessible regions. Railroads helped spur the growth of exports from many familiar regions, including the Languedoc in France, Rioja in Spain, Chianti in Italy and Mendoza in Argentina. While wine could travel on rail cars in standard oak barrels, merchants often built or rented ‘tank cars,’ essentially massive wooden barrels on wheels that could carry thousands of gallons of wine. When the tank car reached its destination, wine could be hosed out into smaller barrels.

The Familiar Glass Bottle Arrives

Although the vast majority of wine was stored and transported in barrels well into the twentieth century, in the seventeenth century we see the introduction of the glass bottle and the cork stopper. Advances in glass making allowed for the production of thicker, harder to break glass, and eventually a point was reached where it was safe to store and transport wine in a glass bottle. Early wine bottles had fat bottoms and short necks. Over time the neck grew and length, and the bottom slimmed – and by the 1820s we see shapes that resemble modern wine bottles.

In 1821, a company called Rickets of Bristol received a patent for a machine that manufactured identically sized bottles, in a shape we would recognize. While bottles are stylistically varied today, standard bottles hold 750ml of wine. Slightly larger and smaller bottles exist, following regional traditions, but their usage has become increasingly rare. Of course larger format bottles such as Magnums exist as well

The use of wine bottles was not common in the nineteenth century. In Britain, for example, it was illegal to sell wine by the bottle – as a consumer protection measure – from 1636 until 1860. If you were a wealthy wine drinker you often owned your own bottles, which you shipped to your vintner of choice. Otherwise you were at the mercy of wine merchants, who received their wine in barrels and bottled it themselves, often adulterating the wine or accidentally exposing it to oxygen. Glass bottles became popular as they offered another advantage: suitability for long-term storage and aging.

Glass wine bottles, like any other vessel, require stoppers. Cork, which the ancient Romans had experimented with, proved to be the answer, although other materials were experimented with, such as oil-soaked rags. Cork stoppers aren’t perfect, but they proved capable of keeping enough oxygen out to vastly extend the practical life of most wines. The small amount of oxygen that permeates through a cork allows wines which benefit from aging to improve over time. You can read about the history of cork and Portugal’s prominent role in cork production here.

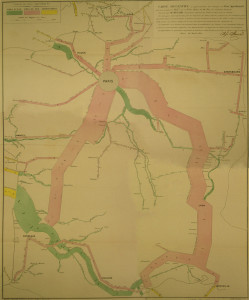

Getting Wine To Soldiers On The Front Line – The French In WW1

While we’ve covered most of the history of wine transportation technologies, looking at the French Army in WWI is an interesting reminder of why humans have spent millennia working to continuously improve these methods. And that’s because we love to drink wine. French soldiers, as was common in all militaries until the mid-to-late twentieth century, received a daily alcohol ration. The French being French, that alcohol was wine, a quarter of a liter per day when WWI broke out. By 1915 it had doubled to half a liter, and by 1916 it rose again to nearly three quarters of a liter. The increasingly large wine rations that the French received are a sad reflection of the deadliness of “the war to end all war.” When you add it all up you get to roughly 317 million gallons of wine rationed out in 1916 alone.

Giant Plastic Bladders, Or How Australia Can Affordably Export Vast Quantities Of Wine All Around The World

While glass bottling became the norm rather than the exception in the twentieth century, often at the vineyard or close by, increasingly globalized trade has dictated a shift in the location of bottling.

Wine, if you haven’t ever picked up a case, is heavy. A full 750ml bottle weighs anywhere between two and three pounds. Shipping heavy things tends to be expensive. Shipping heavy cases of wine, from say, Australia to the West Coast of the United States, and then perhaps all the way to New York on a truck or train, is a problem if you’re selling inexpensive wine. To help with margins, as well as the environment, inexpensive, exported wine, is now often shipped in massive plastic bladders. The Flexitank bags (often referred to as bladders), which were introduced around 15 years ago, can hold over 30,000 bottles worth of wine. When the ship arrives at its destination the bag is delivered to a local bottling facility.

Today, over half of Australia, America and South Africa’s wine exports are transported in plastic. The numbers are growing for other countries as well. Why? The cost savings are significant as explained in Bloomberg BusinessWeek:

While a 20-foot container accommodates about 9,900 liters of bottled wine, it can carry a 24,000-liter bladder at only a little more cost, he says. Sending a container of bottled wine from South Australia, the nation’s biggest wine-producing state, to Europe costs about $3,300 to $3,400, says Ben Mislov, sales manager for Adelaide-based transport company JF Hillebrand Group. Using a bladder only lifts the price to about $4,000, he says.

Plastic ‘bladders’ aren’t the only storage medium used for long distance bulk wine transport. Wine can be stored in ISO-Tanks. These solid units hold similar capacities to their plastic brethren, but are solid and therefore much heavier, which makes for safer, but more expensive transport. If you’re shipping wine over land, Flexitank containers and ISO-Tanks can be placed on trains and trucks. Stainless steel wine tanker trucks also carry wine on long land journeys, a modern update on the old barrels on wheels of earlier times.

Looking In Both Directions

As we continue to develop new technologies to store and transport wine – bags-in-boxes, Tetra Paks, wine kegs, stainless steel barrels, screw caps and artificial corks – the romanticism associated with wine often pulls us back to simpler solutions. After all, few people like to think about the fact that the wine in their glass might have crossed a country or an ocean in a monstrous plastic bladder or a not-quite-full container balanced out with inert gas. While some people might consider turning back to ancient technologies just a gimmick, the Georgian producers fermenting wine in kvevri would argue otherwise. Similarly, those ancient amphorae the Romans abandoned in favor of wooden barrels nearly 2,000 years ago have made a return. A recent article in Forbes highlighted the efforts of two such winemakers:

Andrew Beckham is the unlikely yet ideally-suited leader of the movement in the US. He is a high school ceramics teacher who first bought land in Oregon’s Chehalem Mountains AVA for its timber and suitability as an art studio.

…

Beckham was inspired by a small number of craftspeople around the world who make wine using the terra cotta medium, such as Elisabetta Foradori at her biodynamic winery near Trentino, Italy and the long tradition of winemaking in beeswax-lined amphorae in the Republic of Georgia.

It’s unlikely that the ancient kvevri method of winemaking will be widely adopted, even with improvements to produce a wine that tastes like one our palates are used to. And you’re just as unlikely to walk into a wine shop full of amorphae for the same reason the Romans abandoned them – clay is heavy. What these efforts to do show is a strong desire among a new generation of wine drinkers and wine producers to explore old and new ideas.