Subtlety is not considered to be a particularly laudable characteristic in the beer world. For decades, beer was the basic bitch of the alcoholic beverage sector–cheap, mildly buzz-inducing, primarily consumed by members of the Greek system and Al Bundy types.

Up and coming craft brands gathered a fan base by creating beers in direct opposition to the status quo. Throwing in some flavor curve balls and a few esoteric hops may have been enough to elevate watery lager to “craft” status in the 90’s, but these days getting hot and bothered over a mere pale ale with notes of chocolate and coffee seems as retrograde as sticking safety pins in your ears and heading out to the mosh pit. To merit attention in an increasingly crowded field, brewers are pulling out all the stops–like putting beer in a dead animal and cranking the ABV up to 55%.

In many ways, punk music and extreme beer have followed the same evolutionary path: regarded initially with mistrust by the public at large, soon gathering a core group of followers through artistic excellence and an insider-y spirit of vague disdain for the mainstream’s parallel offerings in their field, slowly garnering critical acclaim among avant-garde members of the establishment, generating widespread interest on college campuses and in hip urban centers, finally achieving critical mass.

The movement’s original core of fans begins to question the merits of successful brands’ new offerings. Accusations of “selling out” ensue. (Actual selling out does as well). So what constitutes an “extreme” beer – and are drinkers still craving this type of hyperactive brew? Or are craft breweries pouring out brews that sound and look good on social media but ultimately fail to deliver?

One extreme beer was made with yeast obtained from whale fossil scrapings, that seems designed more for click bait than the palate.

Specialty craft brewing contributed about $55.7 billion to the U.S. economy in 2014, and funded more than 424,000 jobs, according to the Brewers Association. Within that enormous market, extreme beer is ubiquitous. Almost every producer has a beer that could be classified as “extreme” (for our purposes, that means brews that exhibit out of the ordinary VITA–Vessels used to age them, Ingredients, Time spent aging and/or the ABV).

One thing is clear: for every extremely, legitimately delicious extreme beer, there are a handful of offbeat oddballs, like a creation from Lost Rhino made with yeast obtained from whale fossil scrapings, that seems designed more for click bait than the palate. (Hey, Twitter is a cruel mistress).

It’s hard to believe that many of these aren’t just more flash than cash. (Who really wants to drink a beer brewed with a whole margarita pizza in the mash?) Perhaps in response to some of the excesses of extremism, some the leaders in the field initially–while still cranking out their flagship “extreme” beers — seem, once again, to be breaking away from the pack and racing with trademark chutzpah in a surprising new direction – toward, dare we say it, the basics of elevated beer craft. And the ones who aren’t? They are being left in the (moon) dust.

It’s hard to believe that many of these aren’t just more flash than cash. (Who really wants to drink a beer brewed with a whole margarita pizza in the mash?) Perhaps in response to some of the excesses of extremism, some the leaders in the field initially–while still cranking out their flagship “extreme” beers — seem, once again, to be breaking away from the pack and racing with trademark chutzpah in a surprising new direction – toward, dare we say it, the basics of elevated beer craft. And the ones who aren’t? They are being left in the (moon) dust.

As Russian River’s brew-master and owner Vinnie Cilurzo says, “Extreme beer was always our core business model, it’s just what we do. But I don’t think in terms of extreme and honestly, I don’t think it even exists anymore. Craft brewers have pushed the boundaries so far out, we are actually finding that we are turning away from creating those kinds of beers, and instead, we’re working on our line of lower-alcohol session beers.”

Sam Calgione, the founder and owner of Dogfish Head Craft Brewery and the author of “Extreme Brewing” for home beer-makers dying to learn how to infuse their stouts with chili and smoked pineapple, is often credited as the man who started the extreme beer movement. (Or re-started it – before Prohibition, there were thousands of breweries in the United States, dispensing scores of styles with a wide variety of offbeat “ethnic” ingredients. But after Prohibition, only large breweries that industrialized and utilized basic takes on lager for the most part, emerged and survived. By the 1960’s there was only one craft brewery in America: Anchor Steam.)

Calgione founded Dogfish in 1995, first as a brewery-restaurant-pub, and then rapidly expanding and focusing on its dozens of outlandish, bizarre brews. Dogfish built its hop empire on 120 Minute I.P.A. (a hoppy style of ale created in 18th century Britain for long sea voyages), which comes in at 18% ABV and 120 IBUs (international bittering units). A standard I.P.A. has between 5%-7% ABV and 40 to 70 IBUs.

Dogfish prides itself on its “off-centered” ales, brewed in exotic vessels – like Palo Santo wood sourced from Paraguay – with weird ingredients – like their recent Choc Lobster, brewed with live lobsters – and appears to be staying the extreme course.

Brewing beers made from live lobsters makes awesome copy, and who doesn’t want to be the guy at the party who brings a bottle of ale made from a recipe based on residue found on drinking vessels from the tomb of King Midas or a spiced ale based on residue from pottery found in the Neolithic village of Jiahu? But does it taste good or is it all for show?

Dogfish recently reported a slower year than anticipated for the first time ever.

Dogfish sponsors an annual (already sold-out) extreme beer festival in Boston every February thrown by Beer Advocate, and it is the culmination of what Dogfish does best: create an incredible party for craft obsessives and the reporters who love them. But after everyone scrapes the hop resin from their tongue and sleeps off their hangovers, who will go back for a second bottle of beer made with testicles, Peeps or poop? Not as many people as some of these brewers appear to expect.

Dogfish, a company that has experienced double-digit production volume growth for more than a decade, recently reported a slower year than anticipated. Growth is still up, but it’s in the single digits, according to Brewbound. Dogfish says it will post its 17th consecutive year of revenue and barrelage growth, which is a noteworthy accomplishment for any company. Interestingly, sales for the brand’s 60 Minute IPA is down 3%, while Namaste, a lower alcohol white beer, was the company’s fastest-grower, bringing in 30% more revenue, Brewbound reports.

While Dogfish has most of its hops in the extreme beer basket, the market seems to be craving something a little more mellow that they can drink all night without getting hammered.

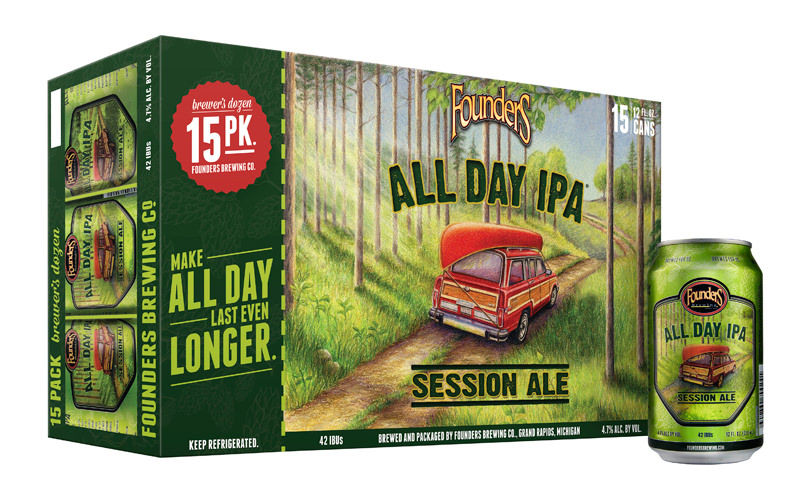

Founders and Russian River come to mind. Founders, one of the kingpins of the big beer movement, now enjoys more than 50% of their sales from a low-alcohol session beer, Founders All Day IPA. Five years ago, Founders’ brewmaster Jeremy Kosmicki and founders Dave Engbers and Mike Stevens, saw a need in their own lives for a flavorful beer that didn’t clock in at 8%-12% ABV he recently told VinePair. All Day IPA was born – it bears the hallmarks of everything extreme beer is beloved for (the fearless intensity of the flavor, the complexity) without the excess (no one-trick ponies in sight, a 5% ABV). Founders was ranked as the nation’s 17th-largest craft producer in 2014 and says it expected to produce 273,000 barrels in 2015, up from 193,000 the previous year.

Russian River started tinkering with new lower ABV beers as well after listening to their favorite customers, all of whom still salivate over the brand’s extreme beers, but say they want something more sessionable after that first hit of hops heaven.

While extreme beers seemed to define the industry for the past decade, now the real growth game is in lower-alcohol sessions with outrageous flavor and legitimate small-batch chops.

“That’s what the community wants,” Vinnie says. “Our best customers want a beer to be extraordinary, but they want to be able to sit down a have a few. So now I’m experimenting in the brewery with lower alcohol session beers. Eventually we’ll go wide with the most successful ones, but for now, I’m seeing what my regulars are responding to.”

Vinnie’s refreshing lack of PR panache has helped him focus on his craft, which as he says, is dedicated to achieving excellence in the glass, whether it’s technically qualified as “extreme” or not.

He predicts the next few years, Russian River will start putting out (and yes, distributing) more and more lower-alcohol beers in response to what he hears from folks in the brewpub.

Bottom line, while extreme beers seemed to define the industry for the past decade, now the real growth game is in lower-alcohol sessions with outrageous flavor and legitimate small-batch chops, but less of a hangover.

That’s pretty punk rock.