There is no denying that craft beer is experiencing a boom. And this is a drastic change from even just ten years ago. At almost any bar or store across the country, one is likely to find craft beer as a possible choice, and those choices continue to multiply. This massive expansion has been so large that macro brewers have taken notice, viewing craft beer’s rapid growth as a threat that is slowly eating up their market share. Budweiser even went on the defensive earlier this year, releasing a commercial during the Super Bowl making fun of the craft beer movement, a clear sign that they are at least a bit concerned with its growing popularity.

And there is potentially good reason for this concern. At this point, craft beer in America represents only 10% (by volume) of the entire beer market. Talk to entrepreneurs and investors and they’ll tell you this fact alone has many of them clamoring to get involved. In their opinion, this small percentage of the total market share still means there is an immense amount of opportunities, with room for almost anyone who would want to enter, which people are doing in droves. The Brewers Association, the nation’s largest craft brew trade organization, has helped stoke these flames. They set a goal of 20% market share by 2020, which they tout in articles like this one from last year, titled BA Insider: Growth In The Craft Beer Segment: Sky Is The Limit:

This growth rate seems frothy by any standard and it begs the question: “Can it continue?” The Brewers Association (BA) has a stated goal of 20% share of volume for the craft segment by 2020. The mantra is “20 by 20.” Based on the trends cited above and the fact that markets like San Francisco, Portland, Seattle and Boston are already above the 20% share mark, it is easy to forget that the many markets across the country are still just beginning their craft journey. For the following reasons many believe 20 by 20 is not only achievable, but a predictable result of demographic, market and growth trends.

Don't Miss A Drop Get the latest in beer, wine, and cocktail culture sent straight to your inbox.

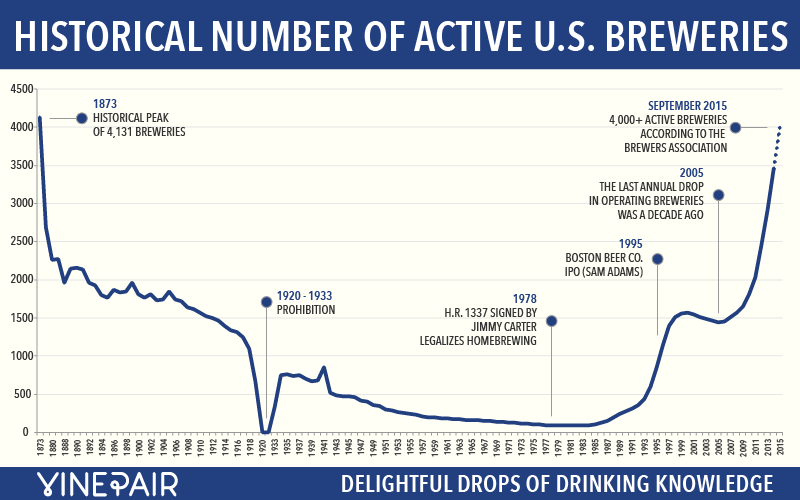

Reasonable or not — and based on shifting definitions of what constitutes craft beer in the first place — this sort of language is reminiscent of other overheated industries where future growth seemed “achievable” and “predictable.” Currently, 1.9 craft breweries are opening a day in the U.S. In the last two years alone we’ve seen craft breweries grow in numbers by 40%, to 3,418 at the end of 2014. 600 more breweries have already opened this year — nearly all presumably craft. It’s a boom similar to the tech bubble, with money flooding in and many of these new breweries convinced they too will strike it rich, or one day might even go public. And it’s these developments that cause one to ask: are we inside a craft beer bubble or does the industry simply need to readjust?

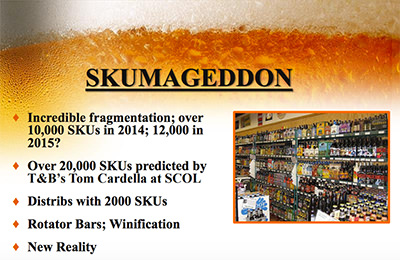

On an incredibly hot day in August, a beer rep for one of the largest beer distributors in New York is hitting the streets of Manhattan with the goal of getting some of the many craft beers the company represents picked up in bars across the city. With so many beers currently on the market, many of the breweries represented by the distributor can only hope that their rep gives their beer the same or even more attention compared to all of the other possibilities on the list. But these distributors have tons of craft beers on offer at this point, which means many breweries with means also employ their own reps to help push demand for their product, but it’s a luxury many start-up breweries don’t have. Competition for tap space has become increasingly fierce.

Rotator bars have become one of the hottest styles of craft beer bars in the country. They’re where beer geeks go to discover new brews, or taste a beer they may have only ever read about. It is these types of bars in which this distribution rep is trying to secure placement for his beers. But getting placement in a rotator bar does not equal smooth sailing for a craft brewery. That’s because with so many craft beers currently on offer, rotator bars can be picky with what they choose, and how often they serve it.

A rotator bar is exactly what it sounds like: it’s a bar that rotates through a wide range of craft beers. The idea is simple: when a keg kicks, instead of replacing that line with the same keg, a new beer goes up. Many of these bars have policies in place that say they won’t serve the same beer within three months of pouring it. And with so many beers on offer, it’s a policy they can easily enforce. But this doesn’t make it easy for the breweries, since a dedicated line is one of the surest ways one can ensure consistent cash flow.

So how did we get to this huge influx of supply and demand in the first place? For that we need to look to the 1970s, and the birth of craft beer as we know it. In 1978 Jimmy Carter signed HR 1337 into law, a bill that legalized home brewing across the country. With this legalization, thousands of people began to take up the hobby of brewing beer and with this influx of new blood and ideas into the brewing space, many of these home brewers decided to take their hobby professional. Across the country, home brewers lobbied their state governments to legalize brewpubs with the most impactful legalization occurring in Washington, California and Oregon — states that would help to fuel the beginnings of the craft beer craze.

From this point on, breweries began to spring up across the country and demand began to grow. Currently there are so many breweries in America that we’re very close to breaking the record set in 1873, decades prior to Prohibition.

We are all living in the greatest age of beer in the history of the world.

— Gary Fish, Deschutes Brewery Founder/CEO and Chair of the Board of Directors of the Brewers Association at the 2014 Craft Brewers Conference

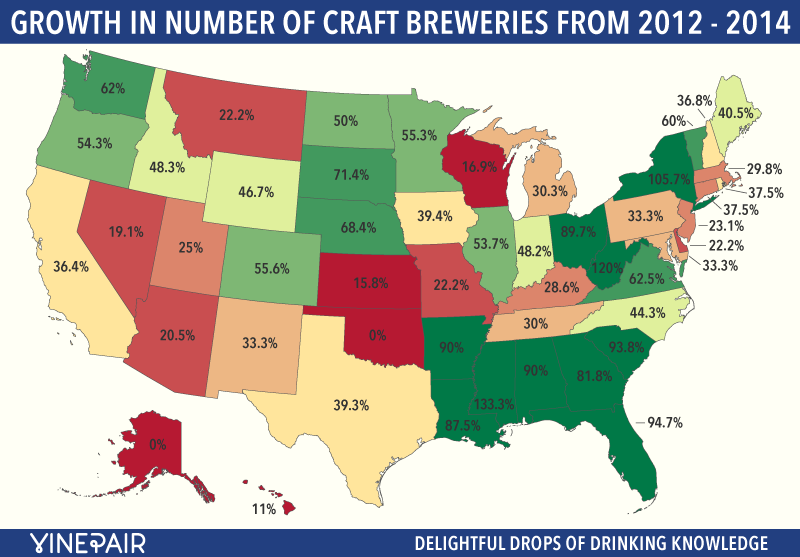

Take a look at a map and one can obviously see pockets of America where there are still only a few breweries in business. And while that may look like a huge opportunity for the future of craft beer, that actually helps illustrate one of the industry’s larger problems: too many new craft breweries are concentrated in markets where competition is fierce and brands are plentiful. If one looks at the craft market as a whole, 37% of the breweries that have opened since 2012 are in the five states which had the most breweries that year. New craft breweries continue to open up in markets that are already flooded with supply, which in turn helps to create the prevalence of phenomenon like rotator bars. Last year 64% of all craft beer was brewed in just ten states.

This concentration of breweries in major markets has also made brand building a challenge for new breweries. While most craft brewers try very hard to compete, the reality is that they simply don’t have the marketing budgets of more well-established players. Ten brewers at the top of the craft beer pyramid were responsible for 43.9% of all craft beer made in the U.S. in 2014 and it’s these brands, with their distribution muscle, that continue to have the most success.1

It would probably be very surprising to most craft beer fans to learn, for example, that the third best selling IPA in the U.S. is made by Samuel Adams, a brewery that until recently wasn’t known for IPA at all. But thanks to its distribution power, the beer has already become a rival to the category’s two leaders, Sierra Nevada and Lagunitas. What does it look like when “the same brewer[] that started a craft beer revolution in 1984” fights back against craft peers by releasing its first West Coast style IPA? Rebel IPA was the best selling new craft beer brand at supermarkets in 2014 – ringing up nearly 4x the sales of the second best-selling new craft brand of the past decade (last year’s runner-up, which would have been the best new brand any other year went to a new “variety pack” from Sierra Nevada). And Boston Beer isn’t letting up; through July of this year the 4th and 5th best new “brands” are the Rebel Rouser Double IPA and the The Rebel Rider (Session) IPA.2

The main reason a brand with massive distribution can quickly become so successful, even when competing in markets where there are arguably better IPAs available, is that most drinkers of craft beer are much more style loyal than brand loyal. It’s much more common to hear a drinker at a bar simply ask for an IPA than to request a specific brand and, thanks to the prevalence of supply, they’re likely to find the style they’re looking for. The success of Sam Adams’ IPA has just as much to do with the fact that more consumers are joining the hoppy beer craze as it is due to the distribution power of Sam Adams; the Sam Adams Rebel IPA happens to be the (not-so) hoppy beer consumers encounter when they’re out at the store.

To fill style demand, there are now more brands than ever, with new ones launching daily. And while many of these brands still raise money and build their own breweries, others have turned to contract brewing.

In the early days of the craft movement, brewers needed to open full-scale breweries before having the ability to mass-produce one of their recipes. But with the demand for craft beer continuing to rise, many brewers are skipping the step of building the brewery first, instead utilizing a contract brewer to manufacture their recipes. Brew Hub in Florida is a perfect example of this contract brewing phenomenon. Owned by billionaire investor Ron Burkle, his private equity firm opened Brew Hub to financially gain from the industry’s explosive growth. Brew Hub takes the contract model one step further, offering sales, marketing and partnership services.3

With our first brewing and packaging facility in Lakeland, Florida, we will become an incubation center for partner-brewers looking to capitalize on the fast-growing craft segment. Our unique, turnkey solution will help craft brewers overcome production and distribution barriers to brand profitability.

— Brew Hub, “About Us”

From the brewer’s perspective, contract brewing frees up early capital to build demand and brand loyalty, a very valid argument given the fact that consumers are currently more style loyal than brand loyal. But the prevalence of contract brewing has also created a backlash within the industry with some arguing this type of brewing doesn’t constitute craft. One famous beer bar in New York City even has created a policy refusing to sell beers that aren’t made at a brewery that is actually owned by the brand.

Despite these issues, supply continues to rise along with demand, but given all of the questions the industry faces as discussed above – of which there are many others – coupled by the fact that beer consumption as a whole is essentially flat, how long will this boom last? And where should the industry be concentrating its growth efforts?

What if 150 decide to go at once? Anheuser-Busch is still buying breweries, but they’ll buy like eight.

— Joe Bisacca, co-founder of Elysian Brewing on why he sold to A-B InBev in January 2015

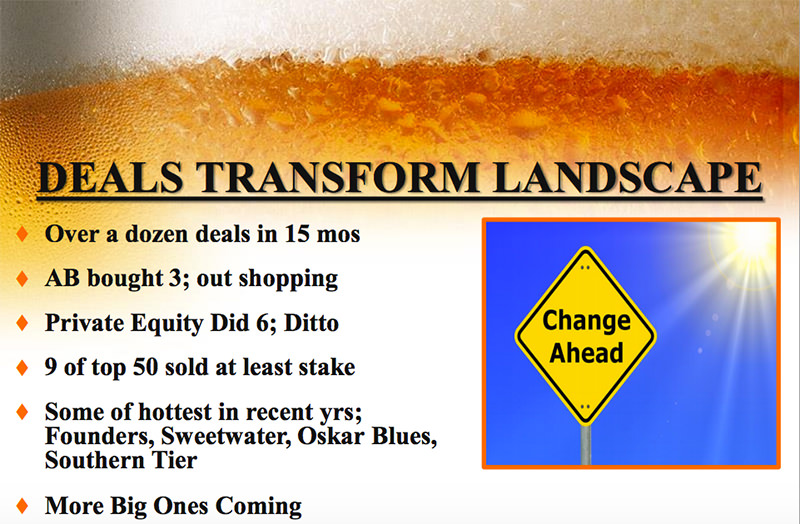

The craft beer industry loves to trumpet its growth along with its continued ability to gobble up market share of the macros, but that growth continues to happen in concentrated areas, which is making it much harder for all but a handful of brands to stand out or truly be successful. Last year, the Brewers Association, the de facto arbiter of what is and isn’t craft beer changed their definition of craft (for the second time in less than five years) to include a number of previously excluded producers. With that change, Yuengling, which many would not consider a craft brewery, displaced Boston Beer Co. (Sam Adams) as the nation’s largest craft brewer. While moves like this will certainly help the Brewers Association hit their market share goals, they also muddy the waters for consumers. This confusion makes it that much easier for the macro brewers to fight back with their own “craft” brands. A recent Nielsen report on the craft beer industry highlighted the confusion over the meaning of “craft” among consumers. Only a slim majority of consumers, 56%, stated that, as it it relates to alcoholic beverages, “craft” means “Coming from a small, independent company.”

Constellation Brands’ record-setting $1 billion purchase of Ballast Point on November 16th perfectly illustrates the question over what constitutes craft, consumer confusion and/or indifference, and the big-getting-bigger phenomenon. Ballast Point had filed its S-1 in anticipation of IPOing less than a month ago. They would be big and public, but still independent. Now they will be owned by a wine, beer and spirits conglomerate that is relatively anonymous versus an Anheuser-Busch InBev or a Heineken. As a result of a complicated transaction related to AB In Bev’s purchase of Grupo Modelo, Constellation, which had imported the extremely popular Modelo and Corona brand families, purchased them — becoming the third largest beer producer in the U.S. overnight. When the deal closes will Ballast Point still make craft beer? It depends who you ask.

True opportunity for new businesses in the craft beer space lies not in becoming a national brand, but in returning to the roots of the craft beer movement. While the macros may continue their craft acquisitions and many of the larger craft brands such as Southern Tier and SweetWater contemplate IPOs and investments from private equity firms, the surest bet for success is in opening a local brewpub in an underserved market. What that success will realistically look like gets to the heart of the debate about craft beer’s future.

Anyone who does want to sell, should be selling right now. Valuations are out of this world. There are people swarming all of us wanting to give us money. In a two-week period, I had 17 different private equity firms that called.

— Steve Hindy, co-founder and Chairman of Brooklyn Brewery, speaking to Reuters in August, 2015.

Large craft brewers, fueled by a wave of investments, are growing rapidly4, with their eyes on national distribution. Facing an increasingly crowded, increasingly concentrated market, realistic long-term success for aspiring craft brewers and brewpub owners looks to be modest and local. Thousands of craft breweries have opened in the past five years, and nearly as many are in planning. If it turns out that these businesses were funded expecting modest returns then we should see the number of new craft breweries gradually slow. If not, we can expect a bust.

But with so many brands continuing to enter flooded markets, many industry insiders believe that while there isn’t a bubble, there definitely needs to be some sort of shakeout. With the rise in supply there has been more and more bad beer released upon the public and that bad beer might turn off a would-be craft fan.

“I believe the craft industry is experiencing a great amount of ‘hype,’” says Mike Stevens, co-founder of Founders Brewing, “but not necessarily defined as a ‘bubble’ that must pop. We believe craft share will continue to grow at a fast pace and can see the day of twice our current market share. However, competition at the local level will continue to swell. This is all good for the industry as more diversity brings more consumer awareness to craft. The ‘bubble’ to me is nothing more than a correction, a thinning out of those not focused on the craft of Craft. The strong will survive and the weak will die has been an applicable statement to many industries. For us in the craft space it’s no different…Quality will survive, lack thereof will die.”

This sentiment is shared by many long-standing members of the craft brewing business. At last years Craft Brewers Conference, BA Director Paul Gatza warned that “While the top end of craft beer quality continues to improve, there are some quality cracks with some of the newer brewers…Many people in this room have spent a lot of time and dedicated a good portion of their lives to building this community that we have today, so seriously, don’t fuck it up.”

1. The top ten brewers with 43.9% share in 2014 are per the Brewers Association’s current definition, which includes D. G. Yuengling & Son and Minhas Craft Brewery. A similar list, compiled by Beer Marketer’s Insights which excludes those breweries but includes Craft Brew Alliance (32.2% owned by AB-InBev) with Brooklyn Brewery sliding into tenth place, totaled a 40.3% share. YoY growth among these breweries ranged from 5.6% to 49.8% with half of them growing faster than 15% YoY. Lagunitas, growing at 49.8%, capitalized on its rapid ascent by selling half of itself to Heineken for an undisclosed sum.↩

2. Off-Premise Sales measured by IRI for the first half of 2015↩

2. Brew Hub also allows bigger players to get bigger faster, supplementing their own production capacity.↩

4. Boston Beer Co., the largest craft brewer has seen slowing growth, particularly in its established beer brands.↩