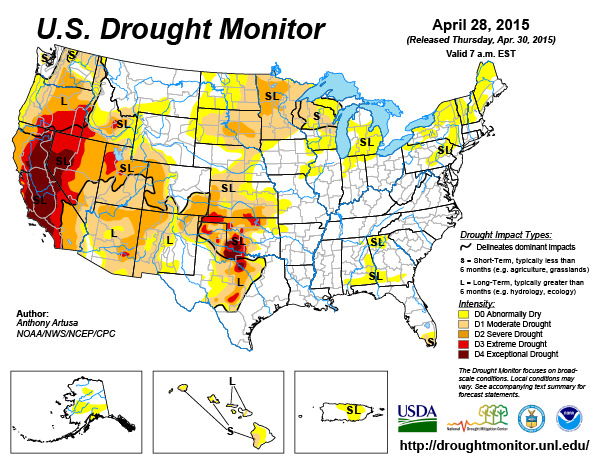

California’s current drought is in its 4th year, and as NASA and other governing bodies declare a State of Emergency and decry the lack of water in the Golden State in the style of Chicken Little, the sky is not falling–at least not for many of the state’s grape growers. In fact, the answer to California’s drought, and the serious sanctions it’s causing across irrigation-dependent vineyards may be even simpler than a rain dance: dry farming.

While it’s often used as a parallel selling point to “Certified Organic” for pricey bottles at swanky wineries, “dry farming” is the ultimate in simple and ancient irrigation techniques. Farmers simply let nature water their crops with rain and residual soil moisture. In essence, dry farming is the Toyota Prius of the wine industry, while traditional drip irrigation–which uses 100-200 gallons of water per vine, per season–is comparable to driving a Hummer H3. A Hummer can dominate almost any terrain, but is usually unnecessary and extremely wasteful.

Wasting wasn’t what the first viticulturists in the Bear Republic–Spanish Missionaries–were after when they planted vines for sacramental wine in the late 1700s. Occupied by their religious duties like converting an entire New World to Catholicism, these monks were far too busy to water their grapevines. As a result, the vines they planted dug deep into the California soil–sometimes over 40 feet–in search of water, developing strong and complex root systems as they went.

Like owning smaller cars, dry-farming is the norm across Europe, and a legal requirement in fine wine regions like Bordeaux and Burgundy. Even in desert-like swaths of Spain, Portugal, and Greece winemakers generally agree that irrigating destroys “terroir,” the mythical combination of soil, climate, and grape variety that makes each vineyard site unique and valuable.

After Prohibition, American winemakers and their pioneering spirits started abandoning dry farming in favor of more scientific schools of grape growing. As climate studies and agriculture became more technical and profitable, so did the American wine industry–and down went the drip lines that keep most California vineyards green, leafy, and high-yielding.

It’s the “high-yielding” part that keeps many farmers away from dry farming, since the practice restricts higher production of the vines. Since most grapes are sold by the ton, heavy, water-laden grapes mean higher profits, and a more lucrative farm.

Drip irrigation, which waters each vine throughout the day like a leaky faucet, became the norm in the 1970s, and over 75% of California’s vineyards still use this method today. The practice keeps vine roots to the top few feet of soil, making them extremely dependent on regular water, and susceptible to drought and disease. It also makes it easy for winemakers to control and manipulate the vines. In effect, drip irrigation is like the emissions from that Hummer–unnecessary and bad for the planet.

Most grape growers agree that wines will thrive with as little as twenty inches of rain per year (about half of the annual rainfall in lush regions like New York State and Oregon), and leaving vines thirsty doesn’t mean poor quality grapes, it simply means fewer grapes are produced per vine. Typically, a single vine’s output equals 2-4 bottles, so a drought year might mean 1.5 or 2 bottles instead of 3 or 4. Obviously, the reduction takes a cut from any winery’s slim margins, but when water usage fees are increasing by thousands of dollars and there are bans on new plantings and well drilling, dry farming isn’t a bad option–and its more socially acceptable than giving up showering.

Proponents of dry farming know water isn’t what the plants need most, it’s sunshine. By letting Mother Nature control the water (the way braking controls a Prius battery) grapes ripen slowly, developing complex flavors. The deep root systems that dry-farmed vineyards develop also protect against vine death in the face of drought and disease. Depending on Nature doesn’t guarantee millions of tons of cheap grapes for jug wine, but it does ensure slow, complex ripening in the grapes, and that’s what winemakers aim for in bottles that wind up costing in the $15+ range.

Many water-loving scientists argue that most of California is too arid for dry farming, but producers like Ambyth Estate and Tablas Creek, who produces over 100,000 cases annually, have shown that areas like Paso Robles, which received only 9 inches of rain in 2014, can still produce fantastic grapes. Though most regions have seen an increase in precipitation in 2015, there’s a palpable feeling of worry in most vineyards this spring, since winegrowers aren’t sure how much longer vines can survive without a normal year of rainfall.

At its core, the wine business is a business and (like any other) driven primarily by profits. Like organic farmers, wine growers committed to dry farming take larger risks, smaller margins, and usually charge slightly higher prices. Franzia and Two Buck Chuck wines could never be dry-farmed, but in the same way Americans are choosing not to support pesticide-heavy factory farms and cruel practices in the meat industry, informed drinkers can choose to help support wineries that conserve earth’s most precious resource, water.