This article is part of our Cocktail Chatter series, where we dive into the wild, weird, and wondrous corners of history to share over a cocktail and impress your friends.

Luxury fashion house Burberry is known for its all-around class, iconic raincoats, and signature beige, red, and black check. The pattern is just as ubiquitous as the Louis Vuitton monogram or Chanel’s interlocked Cs, and over the years, it’s become something of a status symbol of the U.K.’s well-to-do.

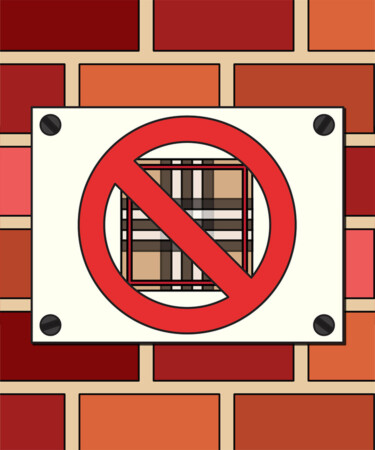

But in the fashion world, trends come, go, and come back again. And in 2003, British bars and clubs turned away potential patrons who showed up wearing any garments by the historic brand. Who turns away good business over something as petty as a brand name, let alone one like Burberry?

Blame the Chavs

In 1997, Burberry went beige check crazy, putting the pattern on everything from bikinis to baseball caps. Within a few years, it became easier for lower-income shoppers to scrape together enough money to buy one or two of the brand’s more affordable accessories. In the U.K., some of these shoppers included chavs.

For those unfamiliar, chav is a (usually pejorative) British term used to stereotype lower-income young people dressed in sportswear. From a fashion standpoint, this brand-loyal subculture carries a similar reputation to American frat bros in Ralph Lauren polos or streetwear fans in Supreme camp caps. Chavs also often roll in the same circles as rowdy soccer fans: We’re talking about the ones who routinely get piss-drunk and stir up a ruckus while spilling lager on the sleeves of anyone in a three-foot radius. (If you’ve seen the 2005 film “Green Street Hooligans,” you know the type.)

In the early aughts, chavs adopted the Burberry beige pattern full-force. Given this rise of Burberry among people who couldn’t generally afford the brand, counterfeiters began pumping out garments adorned with the iconic checkered design.

“It was associated with people who did bad stuff, who went wild on the terraces,” British columnist Peter York told the BBC at the time. “Quite a lot of people thought that Burberry would be worn by the person who mugged them.”

In 2003, a slew of photos of former soap star Danniella Westbrook and her baby dripping in head-to-toe Burberry check popped up in numerous tabloids. At that point, British media had become well aware of chav culture, and the chav-Burberry connection was all over the press.

The Burberry Ban Begins

The Burberry-chav association came to a head that same year when multiple bars and clubs across Britain banned any customers wearing the brand. They didn’t want the mischief the chavs might bring. And for many pubs, it wasn’t limited to just Burberry; the ban applied to any clothing brand associated with chavs and football hooligans. Two pubs in Leicester, the Parody and Varsity, posed a strict rule against Burberry, Stone Island, Aquascutum, Henri-Lloyd, and Rockport.

“Well-known football hooligans have a dress code,” PC Karen Holdridge of the Leicestershire County police department’s violence and disorder team told the Guardian. “These people are recognised as coming into the city centre day in, day out and causing trouble.” According to Vogue, even a few bars in Scotland embraced the beige check ban.

Burberry Strikes Back

Following these bans, Burberry pulled the checked baseball caps from the market, and further removed the iconic checked pattern from multiple products. According to the BBC, the pattern was featured on 20 percent of its products in 2002, and by 2004, it appeared on less than 5 percent. The fashion house also tapped its legal team and started cracking down on counterfeiters and anyone using the beige check pattern without permission.

We’re not experts on British subcultures, but as fashion trends tend to go, the chavs eventually moved on from their Burberry obsession. It’s not totally clear as to when, but both the brand’s legal defensive maneuvers and the widespread pub ban appear to have fizzled out by roughly 2005 when reports of the matter ceased to pop up in various publications. And admittedly, even when the ban was in effect, it did little to hinder Burberry’s reputation on an international scale. In 2004, an unnamed Burberry spokeswoman told B2B fashion company FashionUnited that “[the ban is] clearly a localised issue and to be honest it’s actually quite insignificant in the face of the brand’s global appeal.”

Eventually, the plaid returned to the pubs, and normalcy was restored. But the infamous Burberry ban reminds us that the fashion industry — and the bar industry — can be surprisingly fickle and fragile.

*Image retrieved from pixarno via stock.adobe.com