Not much tells you about a place quite like its indigenous beverage. Aperol and Campari conjure feelings of an Italian summer, bourbon transports drinkers to the American South, and sake evokes Japanese rice paddies. Locale-specific spirits often pull from the flora and fauna of their environments, and the result is the land’s identity in liquid form. There is no Caribbean rum without local sugarcane, nor Spanish vermouth without the country’s ripe grapes.

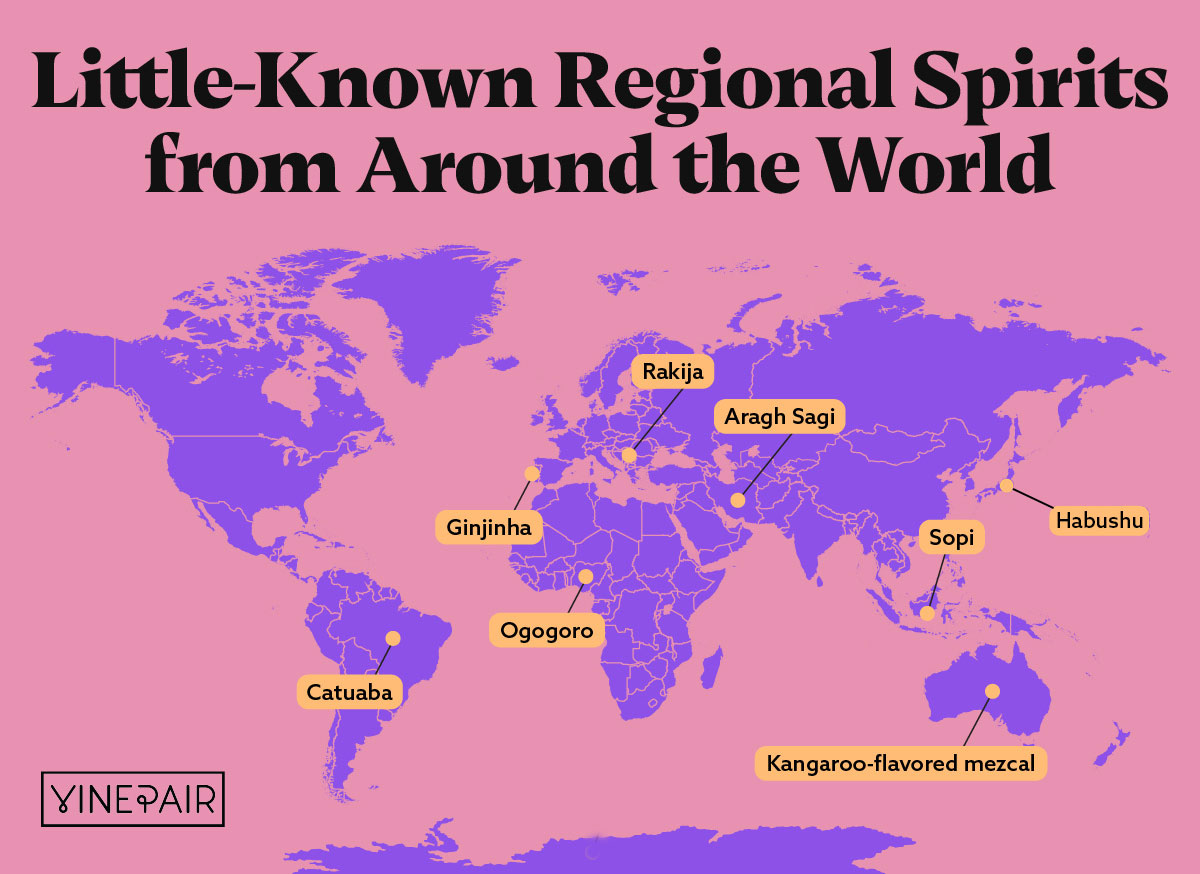

What these examples have in common, however, is their presence in the mainstream. On the other hand, some areas offer native tipples that have flown under the radar, and these liqueurs give drinkers the chance to get a glimpse of another place and culture from a lesser-known angle. They may be hard to find, but next time you encounter one of these regional quaffs, give it a try and see where it takes you.

Catuaba from Brazil

Catuaba — a dark aperitif widely popular in Brazil — is akin to sweet vermouth in ingredients, look, flavor, and method of consumption. Known for its aphrodisiac effects, Catuaba is a red wine-based beverage infused with flavors from native Brazilian plants. The name comes from the catuaba tree, whose leaves macerate in sweet red wine to flavor the liquor. Additions like guaraná, a plant high in caffeine, and marapuama, another tree with aphrodisiac qualities, seep in the beverage before bottling. Other ingredients vary, but most expressions include fermented apple or sugarcane juice. Catuaba can be consumed in cocktails or straight, and it’s particularly popular at Carnaval parties, where younger drinkers reach for it because of its low price.

Ginjinha from Portugal

Ginjinha is a sweet, cherry-flavored liqueur popular across Portugal but ubiquitous in Lisbon. Ginja berries (dark, sour cherries) seep in plain aguardente, a neutral alcohol, and sugar is added for sweetness. Lisbon is teeming with tiny bars serving straight shots of Ginjinha for locals and tourists. The berries remain in the bottle, so bartenders ask drinkers if they want the highly bitter cherry in their glass. Elderly residents set up small stands outside their homes on Lisbon’s steep and windy streets for passersby to buy a taste. Some stands and bars offer chocolate shot glasses for imbibers to eat after drinking the liqueur.

Rakija from Serbia

Rakija is a high-ABV brandy native to the Balkan peninsula. It’s most commonly made from plums, though many variations are produced with other fruits like bananas. Consuming a shot of Rakija — also spelled Rakia — in the morning has been a key ritual in Serbian culture for hundreds of years. It’s the national drink of multiple Balkan countries, and the countries that serve it have a set of unofficial rules to follow when drinking it: Make eye contact during the toast and sip slowly.

Aragh Sagi from Iran

Aragh Sagi is a Persian raisin liqueur with deep roots in Iranian culture. Aragh Sagi — which translates to “dog alcohol” — was popular in the country prior to the 1979 revolution that led to the official ban on alcohol. Since then, it has stayed alive as families developed a clandestine tradition of fermenting and distilling raisins to make their own version. Raisins are extremely abundant in Iran, so when residents were devoid of other alcoholic beverages, using the readily available dried fruit helped them create the underground custom.

Sopi from Indonesia

Primarily made in the island province of East Nusa Tenngara, Indonesia, sopi is a distilled, palm-based liquor. Indigenous communities enjoy it during many traditional gatherings and rituals. The beverage begins as sap from native lontar palm trees, which, once tapped, ferments naturally from ambient yeast in the air. The spontaneous fermentation means sopi typically has a low ABV, though the levels can vary drastically, and some makers distill the fermented sap further for a boozier flavor.

Ogogoro from West Africa

Ogogoro begins as a palm wine that gets distilled into a spirit. The beverage is popular throughout West Africa, and goes under the Ogogoro name in Nigeria, though its label will vary depending on where it is produced. The beverage, sometimes likened to gin, is consumed at bars, restaurants, and social gatherings. It also holds spiritual meaning: At weddings, the fathers of brides offer Ogogoro to the married couple as a blessing.

Habushu from Japan

In English-speaking communities, Habushu is referred to as “snake liquor.” That’s because a venomous, coiled habu pit viper snake sits at the bottom of each glass jug it’s packaged in. The spirit begins with a rice liquor called awamori from Okinawa, the island where Habushu originates. Some producers drown a snake directly in the alcohol, which kills the poisonous properties of its venom. Others kill the animal by freezing it before disemboweling it and placing it in the liquor. The snake isn’t there for flavor — the tradition originates from beliefs that snakes’ venom has medicinal and vitality-boosting qualities. Once the snake is in, honey and herbs join the assemblage for flavor.

Kangaroo-flavored mezcal from Australia

One of Australia’s native liquors takes a page from mezcal de pechuga, which is imbued with a savoriness that comes from a raw chicken or turkey that dangles over the liquid during distillation. Blacksnake, a distillery in Australia, does something quite similar for its pechuga — but with meat from a kangaroo. Nuts, fruit, spices, and — yes — kangaroo meat macerate in the agave-based liquor during the third distillation. The latter, its website says, imparts a nuance of game into the spirit.

*Image retrieved from Mazur Travel via stock.adobe.com