This month, VinePair is exploring how drinks pros are taking on old trends with modern innovations. In Old Skills, New Tricks, we examine contemporary approaches to classic cocktails and clever techniques behind the bar — plus convention-breaking practices in wine, beer, whiskey, and more.

Anyone with more than a passing interest in whiskey will know the old adage about time being a vital component of the spirit’s recipe. And time, as another well-worn saying goes, also equals money. Whether the spirit rests in oak for just a couple of years, or ultimately forms part of a 12-, 15-, or 18-year-old bottling, the financial returns in the whiskey industry are far from quick in their arrival.

For startup craft brands, this complicates matters. And so, new distilleries have two options for driving revenues in the interim: Put out aged spirits produced at third-party distilleries until their own juice is ready, or produce a non-aged clear spirit like gin, which can be bottled and sold almost immediately.

The latter is a tried-and-tested technique employed across every market enjoying a new crop of craft distillers. It’s no coincidence, for example, that as the number of Irish whiskey distilleries grew from four in 2010 to 32 in 2019, the period coincided with a boom in the number of Irish gins on the market. While not all of the newly minted facilities turned their hand to the botanical spirit, the U.K.-based online spirits retailer Master of Malt now lists more than 75 gins produced on the Emerald Isle, noting that Ireland has not been “immune” to the recent gin explosion.

While this is not a uniquely Irish phenomenon, neither is it only startup whiskey producers that are turning to gin. Indeed, some of the world’s best and most storied whiskey distilleries have added a gin to their portfolios, alongside aged whiskeys that have long graced liquor store shelves.

For these distilleries, the incentives for entering the gin-dustry extend beyond the lucrative popularity the spirit offers. Via the juniper-laced clear spirit, distillers can harness their experience while exercising a new level of creativity beyond the relative confines of whiskey. In turn, they can highlight a deeper sense of place, and experiment with new (and old) distillation devices — all with the beauty of time on their side.

Express Yourself

That distilling feels intrinsically more scientific than brewing or winemaking risks overlooking that those who work in the field view it equally as an art form. Craft is more than a marketing buzzword, distillers are quick to remind.

At least, that’s the way Lance Winters speaks about his profession. Hired by California’s St. George Spirits in 1996, the head distiller has long held an affinity for whiskey. He cites a bottle of Lagavulin as being the first product that opened his eyes to the complexity and depth distilled spirits could offer. Winters also famously landed his role after presenting St. George’s founder, Jörg Rupf, with a bottle of his homemade whiskey.

But Winters also recognizes the limitations within the category. And creative soul that he is, his love of whiskey was never going to stop him branching out into other styles.

“Whiskey is a great thing but it’s only one product,” he tells me. “It’s like standing in front of a canvas with a paintbrush and a palette of paint, and saying, ‘From here on out, I’m only going to paint a still life of flowers in a vase with (maybe) a dead pheasant next to it.’ There’s so much other shit to paint.”

In the quarter-century since Winters rocked up with his moonshine, he’s helped transform St. George from being a recognized eau-de-vie distillery, to a respected force within craft whiskey, absinthe, vodka, and gin — the last of which the brand first launched in 2010 and now produces three distinct expressions.

Once again, hearing Winters talk about his role is a reminder of that particular noun having multiple meanings. “There are aspects of who I am as a human being that I can’t express through whiskey, so expressing that through a gin makes a lot of sense,” he says.

As a distiller, Winters views whiskey as a product of performance art while gin is more compositional. To grossly simplify things, producing whiskey involves distilling beer, then sticking it in barrels and seeing where the combination of base spirit, oak, and time will lead. With gin, the process allows him to arrange all the desired components in his head, then tinker with the botanical bill IRL until he’s able to bring his art form to life.

Spirits With a Scent of Place

For St. George’s Dry Rye gin, he leans into botanicals that highlight and complement the base grain’s peppery character. Meanwhile, he seeks to showcase the beauty of California via the brand’s Terroir gin, with Douglas Fir and bay laurel forming the major constituents of the botanical bill.

Some 5,000 miles away on the Scottish isle of Islay, Adam Hannett, head distiller at Bruichladdich, paints a remarkably similar picture. Launched as a standalone brand in 2009, the distillery’s gin, The Botanist, also captures a sense of place.

“With whisky, we can only do so much,” Hannett says. “But with gin we had this opportunity to distill Islay, and all its flavors and scents.”

The Botanist employs full time forager James Donaldson to roam the island throughout the year, and brave fairly rugged weather conditions to hand-pick just enough of the 22 botanicals that will share the Islay experience with the world. We’re not just talking about olfactory experiences, either.

One of those ingredients is bog myrtle, otherwise referred to as sweet gale. Hannett recalls how, as a kid, he would spend summers digging up peats for the winter fires. The young Ileach had to contend with small mosquito-like flies, known locally as midges and widely detested. “If you take bog myrtle, crush it, and rub the oils over you, it’s such a strong smell the midges don’t like it — but it’s a beautiful smell,” he says. “And so you grow up steeped in these things.” (Quite literally.)

On a larger scale, one could point to a similar approach in Japan as one of the reasons the country’s gins have struck a chord with international drinkers. In recent years, two of the nation’s best known names in whisky — Suntory and Nikka — released gins onto the global market that highlight emblematic Japanese ingredients. Suntory’s Roku includes six native botanicals, while Nikka opts for four types of Japanese citrus in its Coffey Gin.

Still Life — Beyond Vases of Flowers

Far from just being an homage to Japan, Nikka’s gin follows in the footsteps of two earlier whisky releases that honor the distillery’s historic “Coffey” stills, which were brought over to Japan in the 1960s. And far from simply being historical mascots, the stills lie at the heart of each spirit’s production and identity, Emiko Kaji, Nikka Whisky’s international business development manager, explains via email.

While not as efficient as modern column stills, the historic Coffey stills allow for continuous distillation with little loss of flavor. They also impart a silky, creamy mouthfeel to the spirit. Each batch of Nikka Coffey Gin contains a complex blend of five total distillates. Three of these are produced in slightly different ways using the brand’s 11 signature botanicals, while botanical-free corn and malt distillates make up the final two parts of the blend.

The production method is “just like making a subtle blended whisky, achieved through batch distillations and skillful blending,” Kaji explains. In this way, Nikka Coffey Gin showcases not only the distillery’s historical assets, but also its expertise in distillation and blending.

Interestingly, Winters and Hannett also point to unique and/or non-traditional stills (for gin production) as being an integral part in their stories.

At St. George, Winters grapples with an eau de vie still, which appears similar to column stills but allows much more control when shaping the final spirit. He describes the differences between the two as being like a whistle versus a clarinet: With a whistle — or column still — the player can blow harder or softer but the same tone will always come through. But with a clarinet, he says, it’s possible to reposition valves to emit different tones.

The Lomond still used to create The Botanist has become something of a legend. Nicknamed Ugly Betty, Bruichladdich’s team salvaged the equipment from a distillery that was to be demolished near Glasgow in 2003. This came two years after Bruichladdich’s modern founders gave a new lease on life to their own distillery, which had sat dormant since 1994. With cash in short supply, they bartered for equipment using barrels of whisky, and salvaged the old copper still, which engineer Duncan MacGillivray would later customize to make it ideal for making unique gin.

“There was this real will to keep with experimental distillation,” Hannett says. “As a whisky distillery, we were different because we didn’t just make one type, we made unpeated, peated, triple-distilled, and quadruple-distilled. We were differentiating and exploring; by creating The Botanist, it was another thing to explore.”

In the Speyside region of the Scottish Highlands, the Balmenach distillery is just three years shy of entering its third century of whisky production. Master distiller Simon Buley accounts for more than two decades of those, and since 2009 he’s also produced the facility’s Caorunn gin.

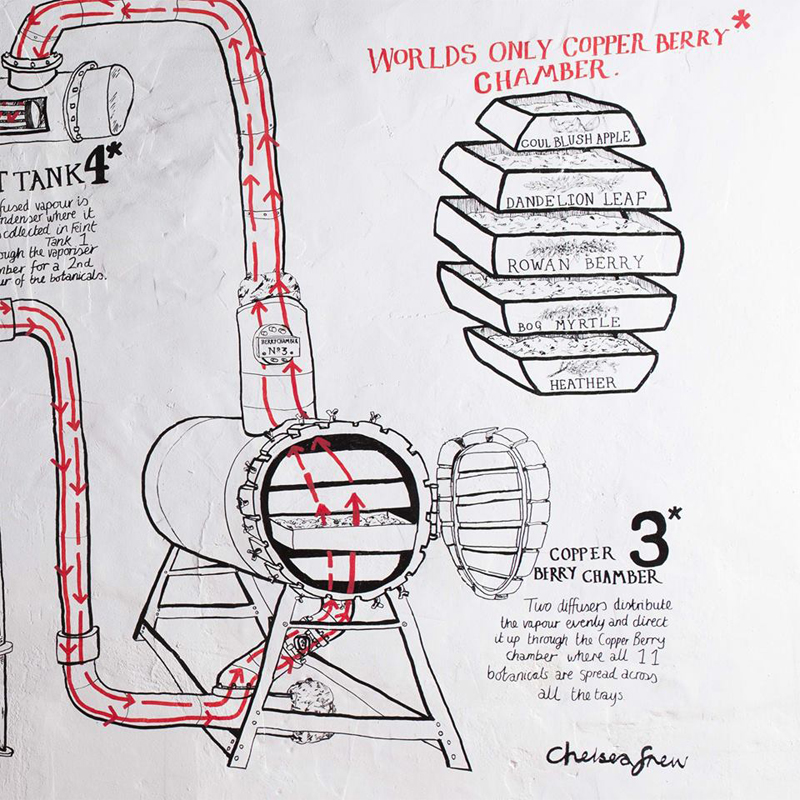

Carounn, too, makes use of traditional local ingredients in its mash bill, including rowan berries, heather, Coul Blush apples, dandelion, and bog myrtle. Buley oversees his own unique piece of distillation equipment: a 1920s Copper Berry Chamber originally made in the U.S. and designed to extract essential oils for perfumes.

But beyond artistic philosophy, terroir, and homages to production equipment, Buley offers another reason why many whisky distillers might be keen to distill gin — and a reminder that distillers and distilleries are unique entities with their own individual legacies.

When he rests his head at night, he knows there’s a good chance that someone, somewhere might be savoring a splash of Caorunn. “I’ve been making whiskey for 23 years,” he says. “As of yet, none of it’s in a bottle for anybody to enjoy.”