Corona has been a mainstay at stateside bars and beaches for decades. The Mexican lager’s clear bottle allows people to see exactly what they’re drinking: a deep-gold brew that may or may not have a couple lime wedges floating in it. Unless your mind is truly in the gutter, Corona’s appearance — or any beer’s, really — shouldn’t innately conjure up the image of chugging pee, but less mature drinkers have still joked about the piss-like hue. But in the ‘80s, a number of whispers snowballed into a nasty rumor that Corona contained actual urine — and that rumor traveled all the way to the top.

It all started in 1987 when Chicago-based beer wholesaler Barton Beers Ltd. began shipping Corona Extra that had been delivered to the Midwest back out to states in the Northeast, where Corona had yet to acquire the state permits necessary to sell its beer. The deal was shady at best, and the beer passed through many hands before reaching its final destination.

“The bottles, long Corona’s biggest selling point, looked like hell by the time they reached the bartops of Manhattan,” author and former beer distributor Philip Van Munching writes in his book “Beer Blast.” “Whether the transshipper had bought inferior product or was subjecting the packaging to incredible wear and tear on the trip eastward, the result was a belief among some drinkers that the brewery was not the most sanitary place.” That general idea, though baseless, hastened the spread of the then-emerging rumor that Corona contained urine.

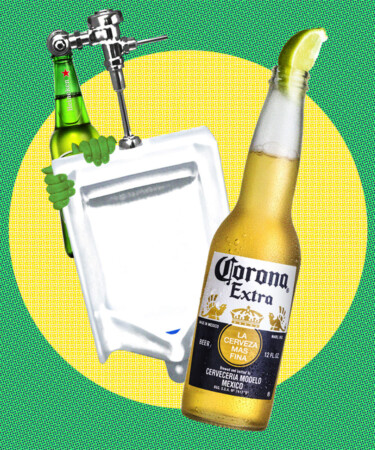

In a July 1987 issue of the L.A. Times, Barton was quoted claiming that one of its Corona distributors in Southern California received 35 separate inquiries about the rumor in a single day. At the same time, word started floating around that CBS News program “60 Minutes” had aired video footage of a sewage ditch feeding directly into Corona’s brewery, even though no such clip ever existed. Van Munching even recalls that a bar around the corner from him had “free Corona refills” signs plastered on the inside of all its bathroom urinals that summer. The damaging hoax also amplified racism toward Hispanic products and culture. The rumor had manifested in many forms, and it began hitting Corona and its U.S. suppliers like a freight train.

These baseless claims were a PR nightmare for Corona distributors like Barton and parent company Grupo Modelo, which had finally tapped into the American market less than a decade prior. By the late ‘80s, Corona was already molding its status as America’s easy-drinking beach beer of choice. The momentum was strong, but when sales suddenly went stagnant — and momentarily tanked in a few U.S. regions — the brand knew it was time for crisis management. Corona hit the news circuit heavily, issuing press releases and securing spots on numerous talk shows for executives to clear the air. The company also spent roughly $500,000 (which equates to a little over $1.3 million in 2023) to broadcast a PSA regarding the hoax.

In an attempt to finally put the rumor to rest, Barton Beers executive vice president and general manager Michael J. Mazzoni did a bit of sleuthing to find out who started spreading the blasphemy. It’s still unclear how exactly he did it, but Mazzoni managed to trace the rumor back to Luce & Sons, a fellow beer wholesaler based in Reno, Nev., that didn’t carry Corona — but did carry Heineken, a competitor the Mexican lager was slowly catching up to.

It’s worth noting that in 1986, Corona sales made up less than half a percent of the total U.S. beer market, so the brand and its suppliers (including Barton) rightfully felt that they were being picked on. “We are one of the little guys,” Mazzoni said in a press release. “And we are dismayed and disappointed that competitors would use dirty tactics to discredit our product.”

Barton Beers took immediate legal action against Luce & Sons, slamming the wholesaler with a $3 million lawsuit. While the initial lawsuit was dropped, Luce & Sons did agree to pay an out-of-court settlement and publicly announce that Corona is “free of any contamination.”

The rumor had legs at that point, so it would take a bit of time before the dust settled. But eventually, the joke got old, and it did little to derail Corona’s sales trajectory in the long run. By 1999, the Mexican lager had surpassed its competitors and had become the best-selling imported beer in the United States — a title that it’s held on and off ever since.