With the rising tides of corporate takeovers in the 1970s, Coca-Coca looked to expand beyond soft drinks. Wine consumption was still relatively low in America at the time, but steady growth beginning the decade prior convinced the company’s senior executives that the wine industry could be a potential target — should the right company come along.

Meanwhile, New York’s Taylor Wine Company was in need of assistance. In its 90-year history, Taylor had grown to the sixth-largest company in the wine business. Yet, a growing inventory and out-of-balance accounts receivables were proving to be an increasing headache. Those factors could have perturbed potential investors, but with a well-established reputation and excellent distribution network, Taylor offered the perfect mark for any ambitious conglomerate looking to enter the business. A perfect fit for both parties, the companies officially merged in January 1977.

During six swift years of Coca-Cola ownership, the Taylor Wine Company experienced a period of boom quite unlike anything seen before in America’s wine industry. With Coca-Cola’s shrewd marketing expertise and eagerness to innovate, Taylor quickly grew to become the second-largest wine brand in the country.

The good times were short-lived. Accustomed to the high margins and fast pace of the soft drinks industry, Coca-Cola’s executives lost patience with the wine industry’s comparatively low profits and soon wanted out. By 1995, following a series of ownership changes and a decade of bad management, the Taylor name was all but erased from American winemaking. A quarter-century on, the one-time wine industry giant remains all but forgotten.

Taylor Wine Company

For the first 80 years of its existence, the Taylor Wine Company operated as a family-run business. Founded in 1880 in New York’s Finger Lakes region, the company moved from its initial home on the Bully Hill above Keuka Lake to the village of Hammondsport in 1919. Unlike many wineries of the time, Taylor not only survived Prohibition but thrived, selling wine-inspired alcohol-free grape juices. The family returned to its winemaking roots after Prohibition’s repeal, producing wines using native American vitis labrusca varieties. But within decades, a combination of sibling infighting and the need for financial injection led the Taylor Wine Company to go public in 1961.

By the time Coca-Cola sought to enter the wine industry, Taylor remained an attractive proposition. The company had an established reputation among wine drinkers, built up over its lengthy history. Its efficient and extensive distribution network made it perfect for any company looking to hit the ground running, even with little experience in the alcohol industry.

While Coca-Cola strove for success, the Taylor Wine Company as it stood was never the intended vehicle to bring it. After the 1977 merger, Coke incorporated Taylor into Wine Spectrum, a new subsidiary division. Believing that the future of the wine industry lay not in New York but California, Coca-Cola execs hatched a plan to create a new brand.

Combining the familiar Taylor name with the resources of the Golden State, the first bottles of Taylor California Cellars would hit the market in 1978 following a few more choice acquisitions: Sterling Vineyards, a renowned but struggling Napa Valley winery; and Monterey Vineyards of Gonzales, Calif.

“We bought Sterling and Monterey for legitimacy — so that we were a real California wine company,” says Andy Harvill, a one-time on-premise brand manager at Wine Spectrum and (now-retired) longtime Coca-Cola employee.

The Judgment of California

Beyond credentials, Monterey Vineyards came with a serious asset that would provide the rocket fuel to propel the new Taylor brand to immediate success.

Richard “Dick” Peterson had some 20 years of winemaking experience by the time Coca-Cola executives came knocking at Monterey’s Gonzales facility. During 10 years spent at Gallo, he’d mastered large-scale wine production and gained an in-depth understanding of consumer preferences. Such experience made him ideally placed to execute Coca-Cola’s plan for its new Taylor wine brand.

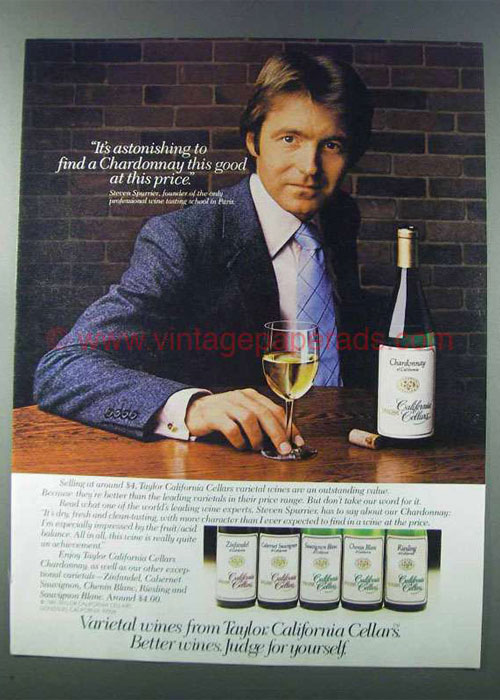

Coca-Cola’s idea was straightforward, if not simple. Peterson was to blend four table wines that would be introduced to the world at a California blind tasting event, pitting them against the leading market competitors. The company expected — demanded — nothing less than victory.

Peterson assured them he could deliver provided two conditions were met. He asked only that he be given the wines he would be competing against ahead of time and that the arranged tasting would include multiple judges. If it were just one judge, personal preference would play too much of a role, he figured. But with 10, 20, or 30 tasters, Peterson was certain quality would prevail.

His theory was proven correct. Tasted alongside wines from Paul Masson, Inglenook, Charles Krug, and Almadén, Taylor California Cellars’ rosé, “Chablis,” and “Rhine” (German-style white) wines clinched top spot in their respective fields. Meanwhile, its “Burgundy” red tied for first place with Charles Krug.

The first phase of Coca-Cola’s plan had gone off without a hitch and the second phase would soon prove just as successful.

An on-hand camera crew and attending members of the press captured the results of the tasting. They were not there by chance. Coca-Cola filmed the tasting with the aim of using the footage as early advertising material for its new brand. They were so convinced by the quality of Peterson’s wines that they took the additional gamble to invite the media along and maybe catch some free press.

“They got what they wanted and it was all on camera,” Peterson says. “Companies usually have to pay for advertising to educate consumers, but the tasting became news on its own.”

Coca-Cola continued its strategy with future marketing efforts. A string of TV commercials and full-page newspaper ads saw high-profile French chefs and wine professionals explaining why they opted for Taylor California Cellars over its competitors. Brands like Almadén and Inglenook were not only called out by name, their bottles featured alongside Taylor’s. Coca-Cola later trademarked the tagline: “Better Wines…Judge for Yourself.”

Though shocking at the time, it’s not surprising Coca-Cola took such a bold approach. Taylor’s debut California tasting followed hot on the heels of the historic 1976 Judgement of Paris tasting, which shot the Napa Valley region to fame and gained international coverage. Even before that, the very same tactic had previously been used against Coca-Cola by its biggest competitor, Pepsi.

But this wasn’t the soft drinks industry and Taylors’ competitors were not impressed. Nor were members of the broader industry.

“I won’t carry that stuff in my store just because of those ads,” Andy Bassin, the owner of a Washington, D.C., wine retailer told The Washington Post. “I think they’re misleading and deceptive.”

Peterson received personal cease-and-desist letters from the rival wineries — not that the ads were his idea — and Coca-Cola faced lawsuits. Peter Mondavi, CEO of the Charles Krug winery, convinced federal regulators to step in. The case went all the way to court.

No doubt aided by Coca-Cola’s financial and legal muscle, Taylor California Cellars won on First Amendment grounds. Better yet, the high-profile campaigns had their desired effect.

“Sales just exploded,” Peterson says. “We sold 500,000 cases in the first six months and then 1.2 million cases over the next year.” Sales hit 3.4 million cases in year three, 5.6 million in year four, and an astonishing 8.2 million in year five.

Taylor’s successes continued beyond the spreadsheet. Not content with disrupting the established order of American table wines, Coca-Cola soon experimented with forward-thinking packaging, inspired by its soft drinks business.

“We introduced bag-in-box packaging for Coca-Cola fountain syrups in the early ’80s, so I asked [why we couldn’t do the same] with wine,” Harvill says. Rather than selling to consumers, the product was marketed to trade, arriving in 18-liter bag-in-box packaging that was ideal for restaurants’ by-the-glass programs.

Coca-Cola also launched a line of 6.3-ounce canned Taylor wines on Delta Airlines — a company with which it shared strong Atlanta roots. The cans were particularly well liked by airlines because they were compact, lightweight, and had a pretty good shelf life, Harvill says. “Every inch of that beverage cart and every ounce of weight are very important.”

The Beginning of the End

Just like the laws of physics that govern aviation, Coca-Cola soon learned that, in the wine industry, what goes up must eventually come down.

By year six, growth started slowing. More familiar with double-digit margins, Coca-Cola’s executives were less than impressed with the 4 to 6 percent profits Taylor California Cellars was posting. The company had also recently invested in a $40 million large-scale production facility in Gonzales, on top of the millions already spent on advertising campaigns.

“When things started to slow down and the accountants realized we were not making much money, or maybe not making any money at all, that’s when things started to … turn sour,” Harvill says.

Harvill partly blames the slowdown on E. & J. Gallo finally taking notice of Taylor and waging war on the brand. Unlike the Coca-Cola-owned company, which relied on bulk wine and still used co-packers for much of its operation, Gallo was completely vertically integrated. It has a glass plant to make its own bottles and a cardboard plant for packaging. Completely privately owned, the company had no shareholders to answer to and could therefore drop its prices lower than anyone else and keep them that way for as long as it took the competitor to tap out.

“They controlled almost all of the distributors — because they were the big bulk moneymaker in the business — and they put a lot of pressure on those distributors to make life tough for us,” Harvill says. “I don’t know if they decided they wanted to put us out of business, but that’s what it looked like.”

By September 1983, enough was enough and Coca-Cola announced it was getting out of the wine business. A New York Times article covering the news revealed Joseph E. Seagram & Sons Inc. was to acquire the Wine Spectrum portfolio for $200 million. Commenting on what may have factored into Coke’s decision to sell, San Francisco-based investment banker Emanuel Goldman said, “Someday there will be a case study on how Gallo responded [to the Coke challenge].”

For his part, Peterson doesn’t fully agree with the Gallo narrative and says the sale came purely from Coca-Cola’s distaste for the wine industry’s inherently low margins. But he is unequivocal in his view that Seagram’s was responsible for Taylor’s subsequent, drawn-out downfall.

While Peterson remained as winemaker for a few more years at Taylor California Cellars, he says the writing was on the wall for the brand from the beginning. A string of poorly judged decisions killed Taylor’s reputation as fast as it had been made. Seagram’s shunned the brand’s excellent distribution network in favor of its own, meaning Taylor ultimately had to fight for supermarket shelf space with another Seagram’s wine brand, Paul Masson.

Given that Paul Masson was one of the wines Taylor had called out in its ad campaigns, distributor sales reps had no incentive to push the newly acquired line of wines — even though Taylor enjoyed a vastly superior reputation and better sales at the time.

Striking the nail in the coffin, Seagram’s hiked the price of Paul Masson (unjustly, in Peterson’s opinion) while simultaneously slashing the cost of Taylor California Cellars. “You cut the price, it destroys the wine,” he says. “That’s well known in the wine business.”

The Taylor brand changed hands again twice in the next decade, ending up at its current owner Canandaigua (now Constellation Brands) in 1993. Sales continued to slump over the course of those 10 years, there were no more innovative product launches, and marketing slogans turned from bold and brash to distinctly uninspiring, including Taylor’s “The Taste That’s Right At Home.”

Taylor’s Gonzales facility remains in operation to this day, but is used for other Constellation brands. It received another multimillion-dollar expansion in 2006, and California’s then Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger was supposed to attend a ribbon-cutting ceremony but had to pull out at the last minute because of a scheduling conflict.

As for Taylor wines, Constellation renewed the trademark in October 2017 and continues to put out a line of dessert wines under the brand umbrella. But in essence, the Taylor name has been dead in the water for the last quarter century.

It’s almost impossible to ignore the irony of this, given that it was the Taylor name that made the brand so attractive to Coca-Cola in the first place.

“We had the momentum to become the No. 1 table wine in America,” Harvill says. “We were that close.”