The rise of craft breweries in the United States is turning into an old story. Year after year for more than a decade, more and more breweries have popped up. Today, there are more than 5,300 breweries in the U.S. — a record that continues to grow. Growth doesn’t last forever, though, and a slowdown was inevitable. While craft beer production grew 13 percent in 2015 and 18 percent in 2014, in 2016, it grew by just 6 percent.

But that doesn’t mean that craft beer growth is a bubble, destined to crash and burn, according to Bart Watson, the chief economist at the Brewers Association, who believes we should be taking a deeper look at the data. The national numbers are misleading, Watson says, and closer analysis reveals a slumbering giant poised to shift America’s major craft beer meccas from the Northeast and Northwest. That giant is the South.

“There’s still growth out there,” Watson tells me over the phone. “There’s variations geographically, and the national numbers tell less of a picture than it used to. We saw 18 percent growth because everywhere was growing; now it’s more place by place.”

Take, for example, Alabama. From 2011 to 2016, Alabama was the fastest growing craft beer state by number of barrels of beer produced. According to numbers gathered by the Brewers Association and published in the latest edition of its magazine, The New Brewer, Alabama produced 6,380 percent more barrels of beer in 2016 than it did in 2011, bringing its production up from a nearly negligible amount to more than 60,000 barrels — which still leaves a lot of room for growth.

It’s not just Alabama, either. Florida was the second-fastest growing state for craft beer in the same time period, and North Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas, and West Virginia were all among the top 10 fastest-growing states.

“Some of it is catch up,” Watson says. “We’re seeing those states come online as great craft brewing states, and some of it’s regulatory changes as Southern states allow more market freedoms and direct sales.”

The South took longer to change Blue Laws left over from Prohibition that stymie the sale and production of alcohol. Brewers in Alabama, Kentucky, and Georgia saw immediate benefits after state legislators loosened regulations, CraftBeer writes. Letting small and independent brewers sell alcohol at the brewery for consumption both at home and on-site opened the market up. Mississippi and Georgia were the last two states to allow direct sales from small breweries.

Direct sales from craft breweries can have a large impact on turning a craft brewery into a profitable business. The volume of beer sold in brewpubs increased 15 percent by volume in 2016, according to the Brewers Association. An anecdotal example of the power of selling house-brewed beer can be found at the Geaghan’s Pub and Craft Brewery in Bangor, Maine. Andrew Geaghan, the co-owner of the brewpub, told the Brewers Association that total beer sales increased 30 percent in the first year Geaghan’s transitioned from pub to brewpub.

In addition to the potential for brewery taproom growth, there’s also room for regional distribution growth in the South, Watson says. There’s simply less competition, and there’s an opportunity for some small breweries to become larger regional distributors across the entire Southeast. That’s not possible in more crowded areas like Washington or Oregon, where brewery territories have already been carved out and there’s little room for new guys that want to grow into regional powerhouses.

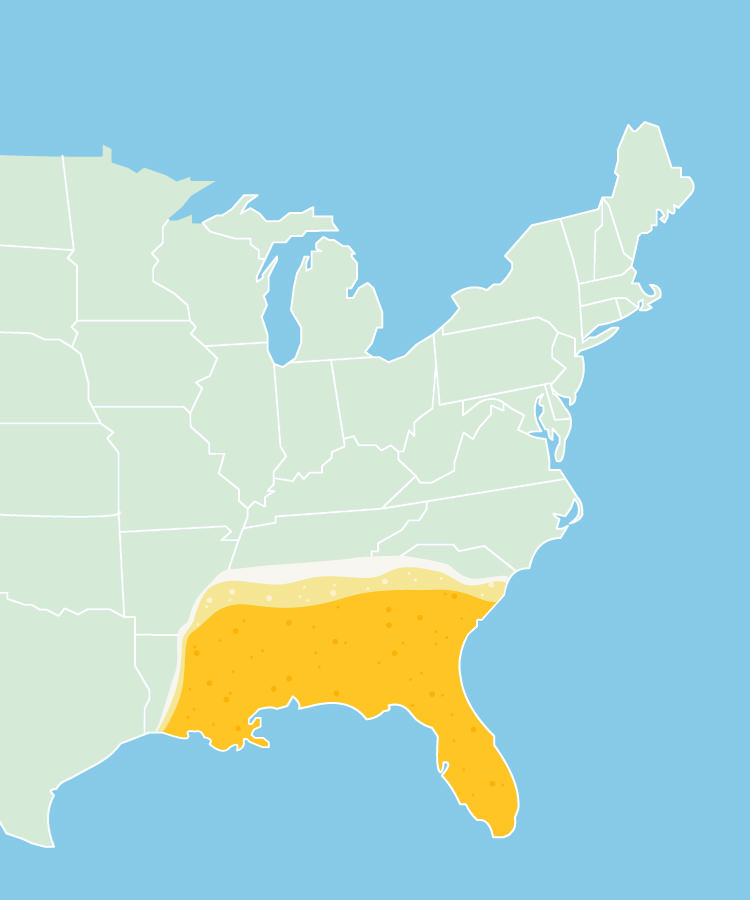

The map for growth can be seen most clearly when looking at the number of breweries per capita in each state. Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Kentucky, Texas, and West Virginia are among states with the 10 least breweries per capita. It’s easier to grow when there are more people who lack a nearby craft brewery.

The meteoric rise of craft beer won’t last forever. When Southern states catch up to other states in breweries per capita as well as in barrel production, growth will start to level off. It’s harder to put up jaw-dropping growth numbers when starting from a higher base. But the growth probably won’t come crashing down.

“I don’t know if people will ever stop saying it’s a craft beer bubble,” Watson says. But just because people say something doesn’t mean it’s true. “Just look at other high-end markets,” Watson continues. “Specialty coffee houses reached a peak, but it didn’t collapse. People didn’t go back to drinking Folgers from the supermarket. It just leveled off.”

Don’t expect to see the leveling off happening in the South anytime soon, though. The slumbering giant is just starting to stretch out. I lived in Alabama for four years, from 2011 to 2015. I saw what Southern craft beer growth looks like first-hand. There was little more than big beer from the grocery store when I first moved to Auburn, Alabama, but by the time I left there was a brewery and multiple craft beer stores, including one that sold beer on tap in gallon milk jug “growlers.” The four local bars had also started to leave at least one tap open for an independent brewery. The data from the Brewers Association about Southern states in general just confirm what I was seeing at the local level while in college at Auburn University. The space and demand for breweries is there; all it takes is someone moving in.