Steven Grasse has mastered the art of navigating the boundaries of the booze world. The FDA’s list of acceptable additives “tells you every single ingredient you’re allowed to use in a spirit,” Grasse says. “If it’s not on the list, you can’t use it. Unless… you can make a historical precedent for why you need to use it.”

That’s when he brought up beaver testicles.

“We found that Swedish immigrants have used beaver balls as flavoring for years,” Grasse says. “They can make a spirit taste very delicious, in fact. We’re releasing it very soon, but we’re still trying to settle on a name.”

Grasse is no crackpot. In fact, more so than perhaps any person ever, he knows exactly what it takes to make an alcohol brand take off.

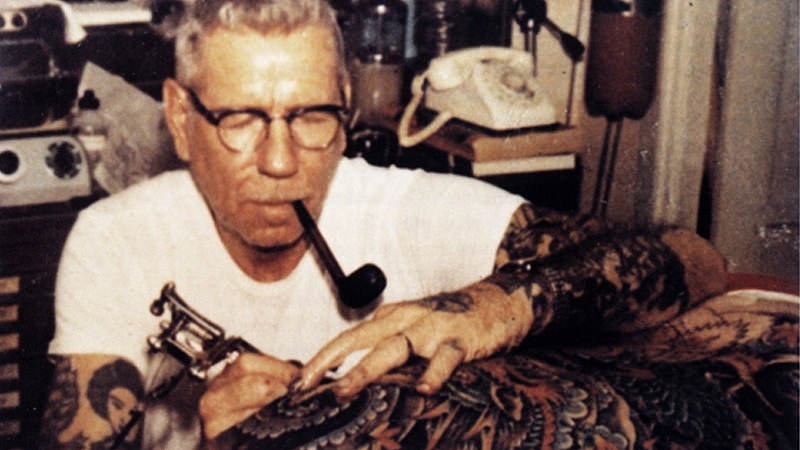

As founder of Quaker City Mercantile, Grasse has created such cult labels as Hendrick’s Gin and Sailor Jerry, a spinoff of a tattoo-inspired clothing line. Nearly 20 years after their launch, both remain huge forces in the spirits world, selling millions of cases. The former is generally credited as the originator of the current wave of oddball botanical craft gins; the latter is currently the second-best-selling spiced rum in the entire world.

“I used to want to be in the movies. The problem with movies is, you do all this work, and they disappear in two to three weeks,” Grasse says. “What’s amazing with spirits, if you do it right, the brand will sell for hundreds of years. Nothing has better brand loyalty — aside from cigarettes — than spirits.”

What makes some spirits go viral is curious. Why do certain alcohols become a sensation, while others languish on retail shelves for years before eventually disappearing for good? It can’t just be about taste. There are too many great spirits continually left unpurchased, and too much garbage selling billions of bottles.

“There’s, what? Six thousand craft breweries, 2000 craft distilleries [in America],” Grasse says. “But I like to say two things: Craft distilling is another word for amateur. And craft distilleries are like assholes, everyone’s got one, and what comes out of them tastes like shit.”

Even if the 2008 sale of Sailor Jerry to William Grant & Sons gave Grasse “fuck you” money, when talking to him you can imagine he was saying “fuck you” even when he had nothing. Perhaps that’s one of the keys to his alcoholic king-making.

With the newfound cash from his previous viral successes, Grasse launched Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, a line of intentionally esoteric spirits in plain-Jane bottles. One is Durt, a parsnip-infused vodka. Those went viral too — to a smaller degree — and again he sold them off to William Grant & Sons.

In the summer of 2015 he finally opened his own distillery, Tamworth Distilling, in the remote White Mountains of Tamworth, New Hampshire.

“I wanted to make a Jack Daniel’s, but even more beautiful,” he says, likening it to the famous whiskey giant that pretty much owns the sleepy town of Lynchburg, Tennessee. “It’s in the most idyllic place possible.”

He brags that Tamworth has two full-time historians and a biochemist on staff, working in a sprawling science research laboratory. There, his team is coming up with the next wave of crazy products he thinks can go viral.

In addition to “normal” products like straight rye, gin, and vodka, Tamworth also produces such oddities as Von Humboldt’s Tamarind Cordial, Turmeric Cordial, Blue Lion Chicorée Liqueur, and a spirit flavored with locally-foraged black trumpet mushrooms. “Our business model is to blow the world away with crazy shit,” Grasse tells me.

But. You can’t expect the whole world to be drinking turmeric liqueur any time soon, can you?

He does. Grasse feels that if you want your product to break out of the craft-distilling “ghetto” (his word) and become a worldwide sensation, four things need to be in place.

- A great liquid that has a reason for being. (“Sailor Jerry was 92 proof,” he says. “That’s 12 proof more than Bacardi for a buck more.”)

- A great story.

- A great package. (“I like to make things look ugly on purpose.”)

- Time.

That last one is important. Taking the time to let a spirit catch on is vital because, Grasse says, there’s no such thing as an overnight sensation in the booze world.

Take Pappy Van Winkle, arguably the most viral spirit there’s ever been. “Pappy” was the owner of the Stitzel-Weller Distillery in the 1940s, where he produced intriguing wheated bourbons. Fast-forward to 1992, and Pappy’s grandson started buying decades-old Stitzel-Weller stock and bottling it himself. This old bourbon had never hit the market, but it didn’t matter. Priced at $80, it mostly sat on shelves until the mid-2000s.

Then bourbon started getting hot again. Around 2012 or so, desire for Pappy Van Winkle finally hit a fever pitch, with people lining up outside stores, entering lotteries, and giving away their first born to land a bottle. It finally went viral, more a rare status symbol than something you drank.

Another slow build success story comes to us from Texas. In the mid-1990s, Bert “Tito” Beveridge started distilling vodka on some cobbled-together Dr. Pepper kegs, eventually finding a loophole in Texas laws to open the state’s first craft distillery. By then he was distilling corn and water from a local aquifer. After several years, in 2001, he finally got a minor break, when Tito’s vodka won double gold at the San Francisco World Spirits Competition.

Sales of this supposedly “handcrafted” spirit slowly started growing after that. Even if it’s made from the same industrially-produced grain neutral spirit just about every other vodka company uses, it’s now the best-selling spirit in America (“First one in wins,” explains Grasse).

Even Fireball, which Grasse slams as “a quick fad,” took forever to finally tip into public consciousness. It was originally one part of a line of Canadian schnapps created by Seagram in the 1980s. Sazerac purchased the brand in 1989 and started marketing it as Dr. McGillicuddy’s Fireball Whisky. In 2007 it was rebranded Fireball Cinnamon Whisky, but, even as recently as 2011, it only generated around $2 million per year.

In 2012, Fireball had an unexpected surge of popularity, becoming the cheap shot du jour among young drinkers. By 2013 it was one of the 10 best-selling liquor brands in the country; nearly 30 years after its introduction, Fireball had finally gone viral.

“You need to tinker and try things,” Grasse tells me. “I tried everything for Sailor Jerry. If it worked, I did more of it. If it didn’t I quit doing it.”

Sailor Jerry didn’t sell well initially. Grasse was thinking about folding up shop and purely focusing on the clothing line when, all of a sudden, it started selling well in Madison, Wisconsin, for still-unknown reasons. So Grasse doubled down in that market and the surrounding areas. Its success soon spread through the Rust Belt, then the Dakotas, then upstate New York, and then “every place that was shitty” Grasse jokes.

“But if I’d spent $20 million upfront [on advertising], it would have been like betting it all on black,” he says.

Grasse also thinks one of the reasons he’s had such success with booze virality is because he’s generally been a one-man show. “What works in my universe is I have absolute authority,” he says. “I can pivot quickly.” On the other hand, he thinks large conglomerates are apt to screw up the grassroots-building of particular brands because they aren’t as nimble.

“We built Sailor Jerry for your average dumb fuck,” he tells me. “You know, guy who buys a bottle and parties at home. It was never for mixologists. It’s made in the Caribbean and shipped up to New Jersey in giant vats. We admit that. But when William Grant bought the brand they wasted lots of time trying to sell it to high-end mixologists. I said, ‘Uh uh, ain’t gonna work.’”

Indeed, after lagging sales for several years, William Grant & Sons finally returned to Grasse’s populist marketing ideas, linking the rum to the legendary tattoo artist, Norman “Sailor Jerry” Collins, for whom it had initially been named.

Meanwhile, Grasse notes that Hendrick’s went viral in the exact opposite way: by specifically targeting fancy mixologists. Eventually, the rose- and cucumber-flavored gin became ubiquitous at top-flight bars. Now it’s at every halfway decent bar in the world.

That model is what Grasse is currently trying to accomplish with Tamworth’s stranger products.

“Turmeric [liqueur] is not going to ever be your base spirit. It’s a [cocktail] modifier. You don’t build a modifier hoping to sell a ton of it,” Grasse explains. He uses strange modifiers as ways to dialogue with mixologists at top bars.

He had noticed many mixologists didn’t like the fact that turmeric stained everything when they worked with it themselves and, thus, greatly preferred something already bottled. Grasse feels if you can get them on your side via these oddball products, the bartenders will help your more mainstream spirits become a sensation.

“Then again, sometimes you do strike gold with modifiers,” he admits, “like in the case of St-Germain.”

Similar to Grasse, Robert J. Cooper, the youthful founder of his own spirits company, had noticed many London bartenders had started using elderflower syrup — a common English ingredient—in their cocktails. That prompted Cooper to release his own elderflower liqueur in 2007. The cocktail revolution was kicking into full gear and, in a bit of a right-place-right-time situation, bartenders were eager to utilize St-Germain in their drinks.

This unlikely hit went so viral it affectionately took the nickname “bartender’s ketchup,” splashed into nearly every drink of the era. The New York Times’s Robert Simonson called St-Germain one of the most significant mixology ingredients of the decade. By 2012 it had been sold to Bacardi for a large, undisclosed sum. Cooper pursued other unique products — a revived take on Crème Yvette, a canned Old-Fashioned — until his untimely death in 2016, but none ever sold as well as St-Germain.

“Ultimately, making more liquid is the best PR strategy you can have,” Grasse tells me. He doesn’t believe Hendrick’s or Sailor Jerry (or Tito’s, for that matter) would find success as single-brand companies if they’d launched today. “I’m gonna keep people talking [about Tamworth] by continually introducing new things to them,” he says.

Which brings us back to the beavers. “I may not sell a lot of my beaver balls liquor, but you’re going to write about it, right?” Grasse asks, “and people will read about it. And I’ll sell a lot more gins and whiskeys because of that!”

Epilogue: The One Time Grasse Didn’t Go Viral (in His Words)

“The worst thing we ever launched was called Spodee. We were doing well and we had some people with money ask us to come up with something. When there’s different partners involved, though, it can turn into a real shit show. At the time we had restrictions on doing spirits with anyone else [besides William Grant & Sons]. So we came up with a wine product.

“‘Wine and shine,’ we said. It was essentially port in a milk bottle, with chocolate sauce thrown in. Here’s the problem: We didn’t have enough control of the process. And the liquid kinda sucked. We also couldn’t get the closure right. When the bottles shipped they leaked all over the place. It was a fucking train wreck.

“Then we did Spodee White — basically a pineapple-tasting white wine port at 24 percent [ABV]. Almost like a pineapple vermouth. If we had not put that in the milk bottle we could have pitched it as a kind of tiki vermouth. And, we would have probably hit right as the tiki boom was coming.

“Hindsight is 20/20, though. I still thinks there’s a fun idea there that could have worked if we’d been smarter about things.”