“If you wish to enhance your enjoyment of wines, please send your check for $15 for a year’s subscription…”

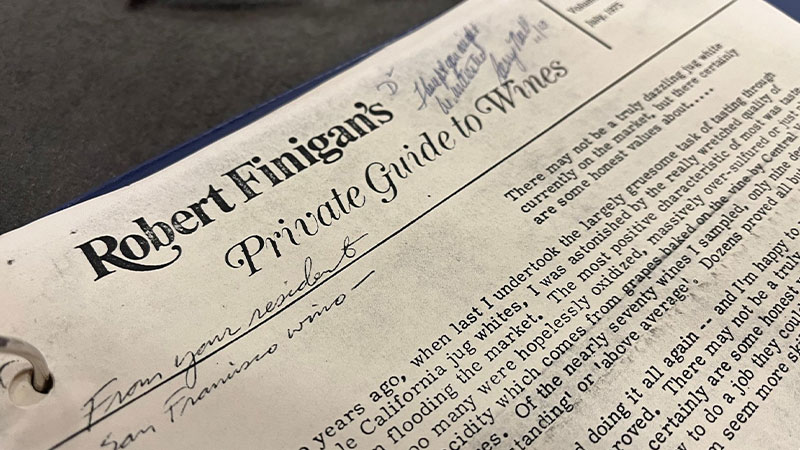

The year was 1975, and — as it had done for three years prior — the message appeared at the bottom of the second page of “Robert Finigan’s Private Guide to Wines.” The newsletters arrived as standard 11-by-8-inch booklets, folded into thirds, and placed into envelopes to be distributed to an exclusively West Coast audience. By the time the publication went national, in October of ‘77, the price had swelled to $20 — $108 in modern-day value — and $36 by 1982. Issues went out monthly from 1972 to 1990, with 12 completing a volume.

Although not necessarily the first newsletter of its kind (that title goes to Robert Balzer’s guide, circa 1970), predecessors lacked the solid readership and market influence that Finigan’s, often shortened to the “Private Guide,” achieved. His success marked the proof of a basically untested concept. But Finigan’s name would ultimately be all but forgotten to history after the emergence of a cocksure competitor, whose radical scoring system not only influenced how Americans bought wine, but how producers made it worldwide.

Finigan’s “Mission”

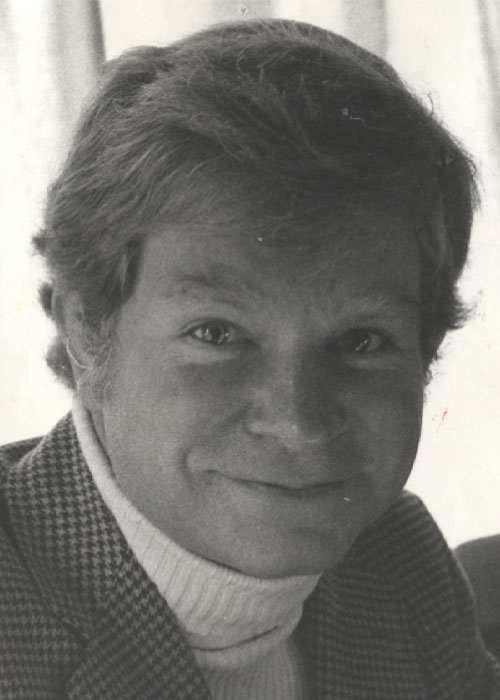

“He was a trailblazer,” says Marimar Torres, the owner of California’s Miramar Vineyards who was also married to Finigan for four years in the 1970s, and remained friendly with him after the divorce. “But nobody knows about him these days. It makes me really sad.”

Dinners shared with roommates at Harvard, where he spent most of the 60’s studying, introduced Finigan to wine. At the end of the decade, he moved to San Francisco to take a job with an international shipping company. He adored the lively and diverse spirit of the city’s dining scene.

For work, Finigan often left the country. One trip took him to Paris and, knowing that he would be there, a wine merchant friend asked if he’d reroute through Bordeaux to taste the 1969 vintage from barrel and report on its form. Already a confident wine taster, he agreed to the “mission.” In his 2006 memoir, “Corks & Forks: Thirty Years of Wine and Food,” Finigan noted, “I was both excited and flattered since I hadn’t yet embarked on my career in wine criticism.” He ended up steering his friend away from the ’69s.

Ultimately, Finigan could not suppress his desire to write and advise on wine. A popular San Francisco publication, “Jack Shelton’s Private Guide to Restaurants,” was for sale and he rallied a troop of investors to secure it. In his memoir, he explained his reasoning: “I thought if Mr. Shelton is deftly guiding people through a mass of restaurants, why shouldn’t someone be doing the same thing with the proliferation of imported and California wines?” In 1972, the first issue of “Robert Finigan’s Private Guide to Wines” premiered.

Rating Without Numbers

Torres notes the system Finigan used in wine reviews. Typically, bottles were broken into the following tiers: Outstanding, Above Average, Average, and Below Average. Adding this dimension to his newsletter was a fresh idea. “Nobody had done that before,” she says. Each bottle inclusion also featured the name of its importer and the prices retailers were selling it for. At the end, Finigan included a description of the wine.

For example, in his December 1978 edition, he scored the Domaine Courcel “Rugiens” Pommard 1976 as “Outstanding.” To modern-day readers of wine reviews, Finigan’s style might seem tempered and intellectual, without the sense of immediacy or the dramatic flavor descriptors tacked onto current tasting notes, especially for a wine judged to be at the top of its field.

“He belonged to a group of men who essentially started the craft of wine writing in the United States.”

“Mme. Courcel’s property has yielded an unusually rich Pommard full of fruit and tannin to match, hard to drink with anything approaching pleasure now, but one certain to reward the patient who give it three to five years of proper aging,” Finingan wrote. “The intensity of this wine, moderately priced as it is, should make the vendors of far more pretentiously valued bottles hang their heads.”

Finigan lent most of his words to Bordeaux and Burgundies, but also to wines from lesser-known French regions like Alsace and the Loire. Occasionally, he’d reflect on wines from Spain, Italy, and Germany. Products outside of Europe were considered, from Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. In fact, he was a strong voice for emerging producers of Napa Zinfandel and Cabernet Sauvignon. Even inexpensive California jug wines found themselves under the scrutiny of Finigan’s palate. All products were considered in their particular context.

Writing During the ’70s Wine Boom

Between 1969 and 1979, wine consumption exploded from 236 million gallons to 444 million, according to the Wine Institute. Before, prolific taste-makers like James Beard, MFK Fisher, and Julia Child regularly explained wine with engaging energy and romance but largely without tactile and educational stuffing. In their narratives, wine was just part of a meal — albeit an important one.

The most well-known American wine writers at the time, one being chateau owner and importer Alexis Lichine, released a limited number of serious books, like Lichine’s classic “Wines of France,” in the style of their more popular British counterparts. But such tomes lacked insight into strategic connoisseurship. Americans with fat pockets had a rapidly growing appetite for the beverage yet no precise authority to tell them how to best spend their money. By directly filling this void in the early ’70s, Finigan became an icon, along with contemporaries like Frank Prial and Alexis Bespaloff.

“[He] wore a suit to tastings or, at the very least, a sports jacket and tie,” says Karen MacNeil, author of the “Wine Bible.” Starting in the industry in the late ’70s, it was with this set of esteemed wine writers, including Finigan, Prial, and Bespaloff, that MacNeil cut her teeth. “He definitely thought of himself very highly,” she says. “He belonged to a group of men who essentially started the craft of wine writing in the United States.”

“Parker’s newsletter certainly wasn’t as well written. But his conviction that his judgments were unassailable was abundantly clear.”

In her biography of Robert Parker, “Emperor of Wine: The Rise of Robert M. Parker, Jr. and the Reign of American Taste,” Elin McCoy notes that the Private Guide enjoyed great success for the first decade of its existence. “At the end of 1981, [Finigan’s] California and National editions had subscribers in every state and thirty-three countries, including Kuwait,” she writes. Unfortunately for him, this was about to change.

“The Private Guide” Wasn’t Fit for the ’80s

Finigan’s approach, although very much his own, was rooted in the older British style, and to American consumers in the 1980s, that was hard to identify with. “It was not a type of wine writing that was inclusive. And it also wasn’t super exciting,” MacNeil says. It was “serious” and “longform.” To McCoy, and perhaps also to many readers at the time, Finigan’s newsletter and opinions seemed to be framed through a Harvard writing program. Meanwhile, a new self-appointed critic appeared on the scene, whose writing certainly didn’t lack snap. This, of course, was Robert Parker.

Based out of Baltimore, Parker launched “The Wine Advocate” while working as a lawyer. He was strongly influenced by the political activist Ralph Nader, who pushed for the protection of Americans from government or business exploitation. He’d shoot it straight. “Parker’s newsletter certainly wasn’t as well written,” McCoy says. “But his conviction that his judgments were unassailable was abundantly clear.”

By being so concise, Parker gave his readers the confidence to enter a club of experts and enthusiasts that Finigan had only been able to orient them toward — and his revolutionary 100-point scale proved the sledgehammer that broke down the door.

Unlike Finigan’s tiers of quality, Parker introduced a grading system. All wines started at 50 points, the base for simply being available, and would score anywhere between that and 100 — a value determined by his own criteria. “The 100-point scale was so easy for people to understand,” MacNeil says. “Parker was able to actually influence sales in a way that Finnegan never did.”

Financial problems at the Private Guide and Finigan’s flip-flopping reports on the 1982 Bordeaux vintage (first declaring that the hype around ’82s was hot air but finally admitting that there were some consumers who might enjoy them) were also detrimental blows. Although he continued to produce his newsletter until 1990, it was quickly eclipsed by The Wine Advocate and bled readership until it ended. Finigan kept up his career, published a handful of books, but did so with little consequence.

“I think he found himself surprised that he didn’t ever achieve the widespread recognition that Parker did,” MacNeil says. However, she notes that “all of us who are writing today have come out of that powerful group in the ’70s,” of which Finigan was a leader.

Finigan, who died in 2011 at 68, epitomized a crucial era in the development of wine appreciation in America, but he simply didn’t fit as an advisor to the generation that followed. In “Corks & Forks,” Finigan finishes a chapter on his friend Alexis Lichine with the line: “What a man. What a legend. What a legacy.” One gets the sense that he hoped for a life that would grant him this same sentiment. While his name isn’t recognized by today’s wine enthusiasts, there are still some who remember Finigan as a treasure.

“He was brilliant,” Torres says. “He was a marvelous person.”

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!