Around 10:30 a.m. on Saturday, Feb. 27, Jen Trimmer, a bartender at Platform Beer Co.’s Columbus, Ohio, taproom, arrived at the brand’s trendy post-industrial downtown location just like she had for all her other weekend shifts for the past year. But that day would be different. After months of mounting frustration over wages, working conditions, and what taproom workers viewed as Platform management’s deficient pandemic response, “we just reached a breaking point,” Trimmer told me in a phone interview this past week.

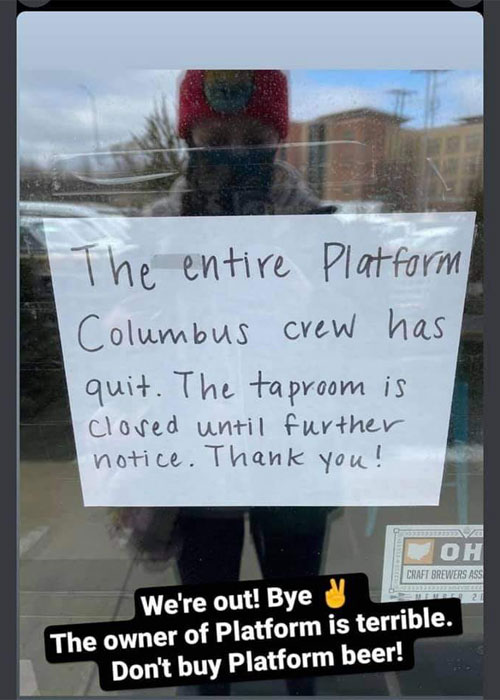

Along with two coworkers, Trimmer taped a sign on the taproom door. Then, they posted an open letter from all six Columbus employees addressed to Justin Carson (a Platform co-founder who, after selling the company to Anheuser-Busch InBev in 2019, remains active in the brewery’s day-to-day operations) in a company-wide Slack channel. In it were allegations of “performative” pandemic measures, unfair pay practices, and an upper management bent on expansion and growth. The workers said Covid-19 cases among staff went unreported, and that an “uncontrollable black mold” had taken up residence in the back cooler.

“We believe it is unethical and unrealistic to expect employees to continue taking on more hours and more responsibilities for the same low wages, all while spending copious amounts of money expanding the brand during a time of crisis when we are hardly getting by,” wrote the workers.

Apparently workers at Columbus’s @PlatformBeerco have walked out! pic.twitter.com/zgXO8qX8P2

— CHAS (@Chaswied) February 27, 2021

Within moments of their Slack post, the taproom phone began to ring. Trimmer and her compatriots figured it was the regional manager, but didn’t bother picking up. They wouldn’t be staying. As they headed out into the unseasonably mild Ohio day — the sort of Saturday that would normally guarantee brisk bar sales and a shot at decent tips — the door swung shut, and the workers’ handwritten sign came into full view.

“The entire Platform Columbus crew has quit. The taproom is closed until further notice. Thank you!”

Of owners and workers

Platform’s Columbus taproom stayed closed that day. A few hours after the walkout, a seventh employee, who had been promoted from bartender to assistant general manager the previous week, quit in solidarity. By Saturday night, with photos of the workers’ letter and sign ricocheting across social media, the company issued a statement on Facebook indirectly acknowledging the full-staff walkout, and promising to address it. “We take this action extremely seriously,” it read in part.

Craft brewers hoping to maintain good labor relations as the coronavirus pandemic enters its second year would do well to take it extremely seriously, too. After almost two decades of “we’re all family” exceptionalism and community-first progressivism, Covid-19 has laid bare the reality of the United States’ craft brewing industry to both its workers and (to some extent) the American drinking public. The reality is simply that it is an industry, and owners profit off their workers’ labor. Without workers — and this is the part that craft laborers have lately come alive to — there are no profits.

This fact was already starting to show through the industry’s threadbare us-versus-them rhetoric prior to the pandemic. In 2019, workers at San Francisco’s iconic Anchor Brewing launched a union drive with complaints that echoed those of workers in any number of less sexy business sectors (not to mention those of Platform’s taproom workers.) They wanted more money, more respect, and more of a say in the direction of their company, which had been acquired by Japanese macrobrewer Sapporo in 2017.

“People are tired of being fed the line that, ‘Oh, you know, if you do what you love, you never work a day in your life,’” one Anchor worker told me at the time. (Anchor’s drive would eventually succeed, making the iconic Potrero Hill brewery one of the industry’s most prominent organized shops.)

Collective action, the craft brewing way

Once the lockdowns arrived in earnest, it seemed the warts-and-all realities of the craft brewing industry became more apparent than ever, and employees have turned increasingly to collective action to solve the workplace problems that the bosses won’t.

Sometimes, this takes the form of union organizing. Unions have represented workers at American macrobreweries for decades; ABI’s 12 major U.S. plants, for example, are powered by the labor of some 4,400 Teamsters. (A spokesperson for the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Ted Gotsch, declined to comment on the situation at Platform, noting only that it does not represent the Columbus workers.) But for all the above reasons — plus a few others, like the industry’s fractured geography and typically small shop size — craft brewing has extremely low union density.

Prior to Anchor’s 2019 drive, there had been only a handful of craft brewery unionization efforts scattered throughout the past decade and a half, and none at such a high-profile firm. Still, 2020 featured at least two public drives at U.S. craft breweries: a hard-fought but failed effort at Surly Brewing Company’s Beer Hall in Minneapolis, and a successful push at Fair State Brewing Cooperative in the same city. One drive in 2019, two in 2020 — these are hardly definitive numbers, but they do indicate an uptick nonetheless. And if you throw in union drives in beer-adjacent craft industries like distilling and coffee, the increase gets harder to ignore.

But labor organizing is hard, slow work, and it offers no quick fix for the acute workplace bullshit — the anti-maskers, the wage theft, the handsy manager who plays favorites — to which brewery and taproom workers are subject on a regular basis. Even without the aegis of a formalized union, the pandemic has given rise to more spontaneous, direct worker action than I can recall in the craft brewing industry in a decade.

In January, workers at Kansas City’s Boulevard Brewing Company threatened to walk off the job unless brewery leaders were held to account for allegations of sexual harassment and assault that former employees had circulated online. Boulevard’s president — who also served as the president of Duvel Moortgat’s U.S. subsidiary, through which the Belgian mid-major had owned the smaller K.C. firm since 2013 — resigned in the wake of that incident, as did Boulevard’s vice president of marketing. “Today, we returned power to the people,” workers wrote in an open letter published to Reddit.

Returning power to the people was front of mind for Columbus Platform workers following the walkout. “I honestly do hope that this can be a start to a broader movement … that people in the industry that are dealing with this exact same thing make a stand,” said Cody Gell, the aforementioned seventh employee at Platform. “I would love to see the service industry in this city or even country as a whole become unionized.”

Platform and the limits of action without organization

Will the walk-off at Platform propel the craft brewing industry toward that future? Or, asked another way: Is this an isolated incident featuring a handful of frustrated workers, or an important point plotted on the up-and-right trajectory of labor organization in the craft brewing industry? It may wind up being both.

That the workers’ direct action momentarily disrupted the flow of Platform’s on-premise profits seems undeniable. After Trimmer & co. walked out, the taproom has remained closed; on Thursday, the brewery announced it would close all its locations until midway through next week.

Here's an update from us: We are temporarily closing today, March 4 through Tuesday, March 9 to give all our employees some well-deserved rest. This includes all our locations and beer delivery. We will be back open on Wednesday, March 10. pic.twitter.com/faKknmfTdm

— Platform Beer Co. (@PlatformBeerco) March 4, 2021

And the brand’s reputation may lose some luster among F&B workers and regular drinkers alike who have been pummeling Platform’s social media accounts with pro-labor sentiments since Saturday. “Seeing everyone else come forward in the comments on social [media shows] that this isn’t uncommon, [it] is a massive problem,” said Gell.

Like her colleague, Trimmer hopes that their collective statement will force Platform’s hand, or ABI’s above it. “We wanted to make sure we [stood] in solidarity with each other and quit together in a way that would make Justin Carson, and Platform as a whole, listen,” said Trimmer.

The walkout certainly appears to have temporarily put the company on tilt tactically. Besides the Facebook statement and the updated closure announcement, Platform has been mostly mum. A spokesperson, Haley Mills, answered my inquiry with a brief statement (included in full below), but declined to answer specific questions about the workers’ allegations or make Carson available for an interview. David McKenzie, head of corporate affairs for ABI’s craft business unit, the Brewers Collective, referred me to the same statement Mills issued, but would not comment further.

Whether all of this will add up to real, lasting change at the firm, however, remains to be seen. Worker accounts and available sales data indicate Platform has maintained a strong financial position throughout the pandemic. According to the letter, managers had repeatedly crowed about “shattering our goals,” galling the Columbus bartenders who “work seven or eight hours to walk away with $12 in tips.” Trimmer told me that business at the Columbus taproom had been “booming” through spring and summer 2020, but had no on-premise sales figures to share.

Still, a review of Platform’s off-premise sales (the beer for which is produced and packaged at Platform’s Cleveland plant) suggests those goal-shattering claims weren’t just boasts. Nielsen scan data provided to VinePair by Bump Williams Consulting shows that Platform’s retail sales across supermarkets, convenience and liquor stores in 2020 totaled over $5.1 million — a 74 percent increase over the brand’s 2019 figures. And for the most recent 12-week period tracked across those channels, sales were up $461,000 (66.3 percent) compared to the same period last year. (Sales of Platform’s seltzer totaled another $191,000 on their own.)

“Maybe we’ll look back on this and be like, ‘We should have made those demands, we should have bargained before we left,’” said Trimmer, who emphasized that she was still learning about labor rights and protections. “Maybe hindsight is 20/20 that way.”

Of course it’s possible that the resignation en masse at Platform triggers top-down change, or that other workers at the company, inspired by their Columbus colleagues, pick up organizing where they left off. And maybe the company will even find a way to bring the walkers-off back into the fold. According to Trimmer and Gell, Platform’s Carson, with an HR rep, called all seven ex-employees individually on Monday. Wary of divide and conquer, the workers countered with a letter requesting a virtual meeting, which has gone unmet. Barring such a reconciliation, though, any future worker wins at Platform will be vicarious ones — a tough pill to swallow after taking such a brave stand.

Such are the limits of direct action without a structure of solidarity to underpin sustained pressure. In organizing terms, Platform’s workers already did the hard part: They convinced an entire shop to stand together with the common goal of improving their workplace. Trimmer said that the workers had toyed with the idea of including demands in the letter and trying to bargain with the company, but by then, after a year of pandemic stress, they’d hit their limit. “I think we were so personally done with the company,” she said. “It felt like the best, or the only, way to get them to listen was to have a mass walkout.”

To paraphrase the old labor saw, the breweries that face collective worker action are the ones that deserve it. It speaks volumes about the situation at Platform that seven workers decided, in the middle of the pandemic, that they were better off without these jobs than with them. But if craft brewing industry employees are to enjoy the fruits of their collective action, and to deliver brewhouse and taproom labor unto the service industry’s “broader movement” like Gell hopes, they’ll have to find a way to build worker power and pressure management without sacrificing themselves in the process. Put simply, they’ll have to organize unions. Will they?

Platform Beer Co.’s emailed statement to VinePair: “We are continuing our meetings with all employees from all locations to encourage an open dialogue. We met with many of our team members on Monday and Tuesday, and we’ll continue these discussions through the end of this week. Platform is committed to learning more and moving forward in a positive way.” — Justin Carson & Paul Benner, Co-Founders, Platform Beer Co.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!