Like time, consumer outrage flies on the internet. Earlier this month a line of incredibly ill-conceived novelty wines tied to “The Handmaid’s Tale” inspired such immediate digital fury that the distributor, Lot18, canceled the wines one day after they were announced.

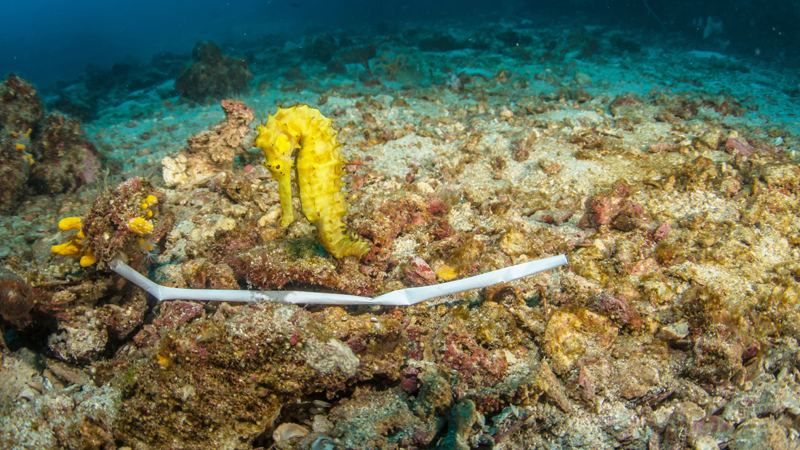

Now we’ve turned our collective grimace toward plastic straws. Three years after a video of a sea turtle with a straw lodged in its nostril went viral, resulting in some 31 million YouTube views, plastic straws have gone from everyday amenity to single-use scarlet letter.

The internet is roiling. In June, The Atlantic published a historical analysis of straws and capitalism, “Disposable America.” Bloomberg provided a counter-take, “Plastic Straws Aren’t the Problem,” highlighting their relatively small ecological footprint (.03 percent of 8 million metric tons of plastic waste annually).

Bitch Media offered a counter-counter-take, saying straw bans reek of ableism because some disabled people rely on bendable plastics. The Washington Post and CNN then also explored this angle.

The digital controversy is generating real-time results. Plastic straw bans are proliferating in ecologically minded bars, restaurants, airlines, and hotel chains. Entire municipal districts, including the city of Seattle, have announced embargoes. Demand for sustainable alternatives is reportedly now outpacing supply in some circles.

Plastic straws are going haywire because, unlike overhauling waste management or recycling legislation, they’re accessible. Straws are tangible in the most literal sense: We hold them in our hands.

According to one debatable figure, Americans use 500 million plastic straws a day. I confess that I sipped iced coffee via a plastic straw this morning. (Said straw was labeled “Eco-Products: 100% compostable,” but more on that later.)

Institutional change is daunting. Banning plastic straws seems like something we can actually do, not just something we can fight about on the internet. Whether or not eliminating them is all that impactful is beside the point.

Nick Kokonos, bar manager of The Grocery in Charleston, S.C., is one of many hospitality professionals currently operating plastic straw-free businesses. The Grocery participated in a citywide “Strawless Summer” promotion in 2017 and never looked back.

“It makes sense for us,” Kokonos says. “Our goal is to reduce the amount of waste we are producing.” The Grocery also composts food waste and repurposes used paper into coasters and menus.

The bar no longer “automatically” serves drinks with straws, Kokonos says, but it does provide compostable paper straws on request.

Turns out, very few people ask for them. Kokonos estimates The Grocery has used about three boxes, or 3,000 paper straws total, since introducing the eco-friendly option more than a year ago. Back when The Grocery put plastic straws in every drink, it went through nearly two boxes a month, or 24,000 plastic straws in a year.

Granted, paper or reusable metal straws are more expensive than plastic ones. A “party pack” of 500 bendable plastic straws costs $7.35 on Amazon. A pack of 200 paper straws is $9.49. Meanwhile, a set of six reusable metal straws is $9.99, as is a box of 50 compostable straws.

“The cost to us will be four times higher,” Joe’s Coffee owner Jonathan Rubinstein told Bloomberg of its decision to switch to compostable straws in its 18 locations.

As with most sustainability measures, however, the long-term ideological shift can pay dividends. Kate Icopini, general manager of St. Jack, a cafe in Portland, Ore., recently told Eater her restaurant has saved approximately $800 in the six months since it eliminated straws.

Instead of ordering its usual plastic straws, St. Jack “purchased about $60 of metal straws from Amazon,” Icopini says, and offers them to customers on request. The restaurant also provides bended metal straws to accommodate diners with physical disabilities.

Manhattan’s Breads Bakery, where I purchased my iced coffee this morning, only stocks plant-based, recyclable straws. By neurotically close analysis I can say the eco-straws feel a bit stiffer and firmer than their single-use plastic brethren, but the differences are negligible.

The Polynesian, a newly opened NYC tiki bar, also uses compostable straws. Chicago’s Revival Food Hall and DK Restaurant Group are plastic straw-free. The Lettuce Entertain You restaurant group, comprised of 60-plus brands including tiki bar Three Dots and a Dash, is in the process of eliminating plastic straws, as is Intelligentsia Coffee.

Skeptics argue the ecological impact of plastic straws is minimal. That’s not really the point, though. “More people are becoming concerned about their individual impact on the earth and are interested in taking action to do something,” Joseph Boroski, bar director of The 18th Room in NYC, writes in an email. The 18th Room, like The Grocery, is sustainability minded. It repurposes citrus rinds into shrubs, and dried banana peels into garnishes.

Just as seeing an endangered turtle made consumers start thinking about where their straws go once they’re done stirring — “People are going to have issue with anything that has a cute face,” Kokonos says — the plastic straw ban could serve as a catalyst for consumers to consider larger waste issues.

The hospitality industry generates what NPR calls “a staggering amount” of waste. American restaurants alone surpass 571,000 tons of food waste per year, not counting “the amount of other resources they use,” writes Maanvi Singh in a 2017 piece, “Warriors Against Waste.”

One of those causes could be making recycling more accessible to everyone, not just those in America’s notably “green” cities like San Francisco and Seattle. “The problem is waste collection and the lack of recycling,” Caroline Wiggins, CEO of the U.K. company Plastico, told CNN (though it seems fair to say she has a horse in this race).

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. generates 30 million metric tons of plastic waste annually. Even if straws account for “.001 percent of that, it’s worth it,” Kokomos says.

Connie Baker, head distiller at Marble Distillery Co., a zero-waste operation in Carbondale, Colo., calls the plastic straw ban “a great first (baby) step.

“The fact that this ban seems to be getting a lot of attention, and perhaps becoming infamous, will naturally lead to additional initiatives the industry can adopt,” Baker writes in an email.

Statistically this is true. “Research has proven that public awareness campaigns — when backed by science— guide overall behavior toward more sustainable consumption,” writes Quartz. Boroski compares the momentum around plastic straws to the rise of reusable shopping bags, and Bloomberg compares it to the dolphin-free tuna campaign of the 1990s.

Humans may be predisposed to resist change, but we are also social animals. If we start thinking everyone else is recycling their cardboard, ditching plastic bags, and buying sustainably-fished tuna, we will slowly but surely start to come around to these behaviors. We don’t necessarily need to understand the science, either. We just want to know it’s out there.

“We know change takes time, but times are changing,” Baker says.