Nightlife is always changing. Clubs and bars open and close. In New York, Club Cumming just came. Word is that Continental is going.

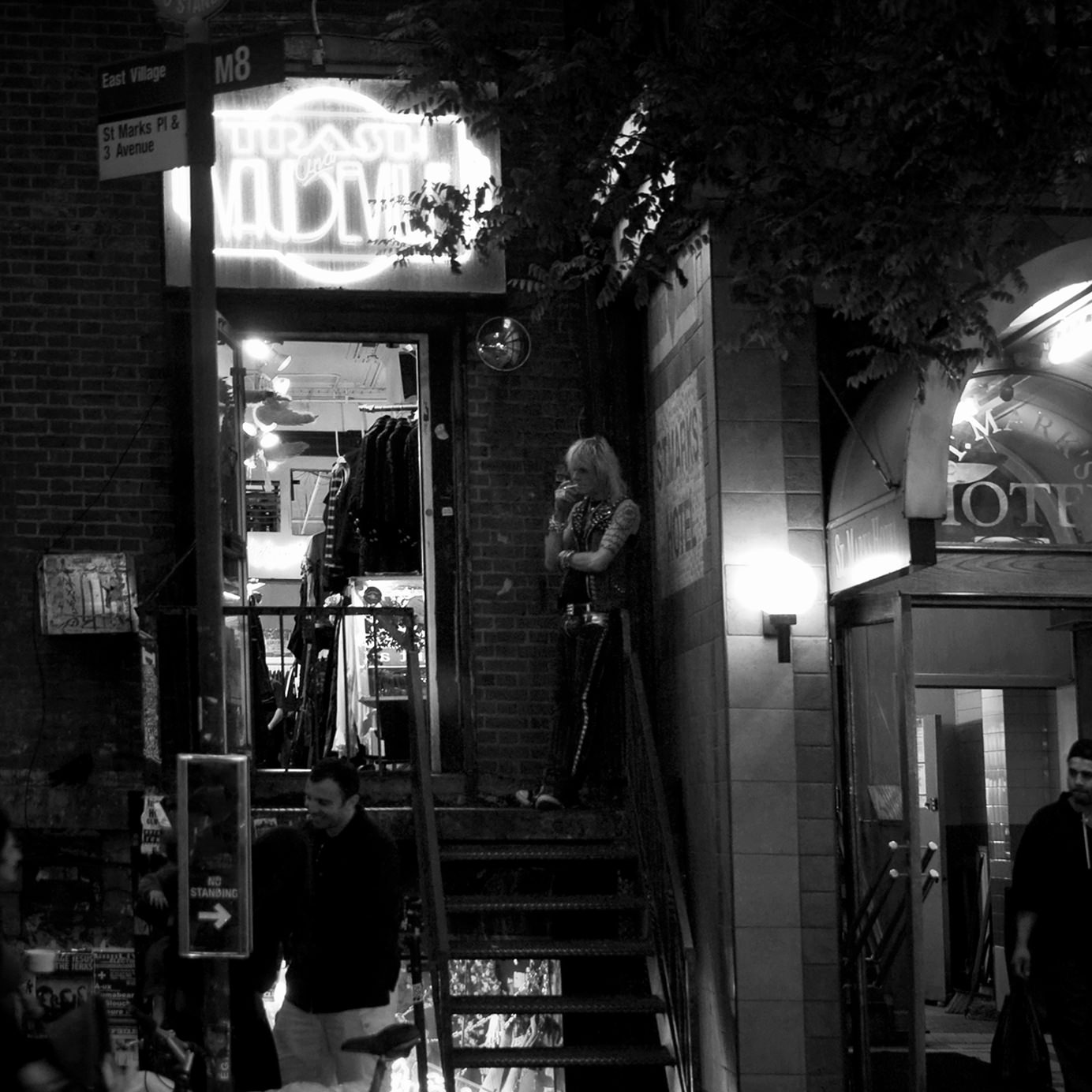

Continental is a bar right off St. Marks on Third Avenue in NYC’s East Village. If you’ve seen it, you know it: It has a big signing proclaiming “5 Shots For $10.” It’s an offer too good to be true, sure, but it will soon be replaced with another, all-too-recognizable sign for some bank or supermarket chain that can afford the rents, evicting Continental and its old-school neighbors.

This corner of St. Mark’s was once a creative hub. Continental started out as a rock venue, played by The Ramones, Iggy Pop, Guns N’ Roses, Patti Smith and Lenny Kaye, and Debbie Harry. They were succeeded by Blues Traveler, the Wallflowers, Joan Osborne, and the Spin Doctors, a veritable chronology of late-20th-century music.

In today’s East Village, rock venues are as rare as “I’m With Her” buttons at a Trump rally. Around the corner from Continental, a coffee chain sells caffeine where the historic St. Marks Bookshop once peddled enlightenment. Our city’s rich heritage is dying from a thousand pinpricks. What happened?

The Continental Divide

Trigger Smith, the owner and operator of Continental, is a survivor. His is a lesson to be learned by operators everywhere.

Back in 1991, “you couldn’t walk two blocks in the East Village without running into musicians and artists who played or hung out at my club and hung out in the neighborhood,” Smith recalls. Celebrities like Steve Van Zant, Ronnie Spector, Lenny Kravitz, Scott Weiland, Cheap Trick, Liv Tyler, and many more hung out there. Yet with that hoopla, the place just wasn’t making money.

Smith was often at the door trying to make ends meet. The hours, paying the bills and the constant hustle took its toll. “It put me in a bad mood for 15 years,” he says. He needed to change.

“I had some debt in year 15 and it was getting worse,” Smith says, “So I took a chance and changed the concept. And it did help pay off the debt, so it was the right move.” The concept was laid out in bold letters across that banner, promising five shots for an incomprehensibly low $10 on one of the highest-traffic corners in the area.

Some people laughed. Others thought it cheapened the rich culture of St. Mark and were indignant. The crowds swarmed in and the business survived.

“The five-shot deal isn’t a money maker, obviously,” Smith says, “But it does bring people in and hopefully they’ll buy a beer or two” Unfortunately, Smith recalls, many didn’t. “And they look at you with contempt when we don’t give them tap water with their five shots.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/BVDohBijGXw/?tagged=continentalbarnyc

Smith’s Hail Mary move bought his venue some time, but now Continental is drifting toward the horizon. Its historic East Village intersection is being developed into a seven-story structure with two floors of retail and offices above. McDonalds, Continental’s longtime neighbor, sits empty like a tomb, awaiting the takeover. (We all knew change was coming when McDonalds closed.)

Smith won’t survive this time. With any luck, come August, he’ll move onto No. 7 of his nine cool-cat lives and begin again.

When Rock Hits a Wall

“Several years ago there was a very strong scene for live music in Manhattan and Brooklyn, especially for bands that use electronics and synthesizers in a live setting,” Zachary Allan Starkey, musician and songwriter of the band ZGRT, says. He recalls playing venues like Pianos, Lit, Fontana’s, The Cake Shop, and Home Sweet Home/Nothing Changes in Manhattan’s East Village and Lower East Side. Exciting, multi-genre music scenes were built around these venues.

By 2017, most have closed or are focused on DJ or club nights. Other than Bowery Electric, which tends to bring in older (and awesome) artists, there is hardly any music scene in New York’s East Village or Lower East Side. “It’s difficult to get newer audiences that are now mostly based in Brooklyn to go to a show at Bowery Electric in Manhattan, which is a shame,” Starkey says.

Finding a good live music scene anywhere in New York gets harder by the day. Williamsburg’s is gone; the death of Cameo Gallery was the last gasp. There is a small DIY live music scene in Bushwick; Bossa Nova Civic Club sometimes hosts lo-fi live sets among its DJ nights. Silent Barn and Market House still put on live shows, as do Trans-Pecos and Footlight in Queens. C’mon Everybody is a great venue, and the Gateway on Broadway has some live music.

The fact is, as 2017 draws to a close, New York’s rock scene has hit a wall.

Now DJ-based club nights dominate nightlife culture. For an owner/operator, it’s easier to make money with a DJ. The venue simply pays the DJ a fee, regardless of how many people show up and pay to get in. There is very little production cost.

For live music, most venues pay the sound person, and sometimes even the bartenders and bouncer, out of ticket sales. “This is why more venues are interested in club nights than live music nights,” Starkey says, “And as a musician this makes me sad and frustrated.“

Stages take up room. Soundboards and light boards take up room. Dressing rooms take up room. Technicians cost money. Then there’s the load-in and load-out, and the advertising, and the bar stopping dead when the band is playing. Square-foot revenue streams are important, especially when you’re operating in a corporate real estate arms race, like NYC.

It’s easier to just put a table in the corner for a DJ. The only remaining question is, where will we hang the next “5 Shots For $10” banner?