Recently, in one of the outdoor cabins that comprise the Covid-era “winter village” outside the Japanese restaurant Rule of Thirds in Brooklyn, co-owner George Padilla opened a bottle and poured it into an ochoko, the little ceramic sake cup I had chosen for myself. Then, he poured for himself. We were partaking in a ritual that is seasonal in Japan, the drinking of unpasteurized sake, called namazake.

In March, when the cherry trees are erupting in pink buds, people gather in parks with bento boxes of vegetables cut into the shapes of cherry blossoms, rice sprinkled with dried salmon the color of the seasonal blooms, and rosy-hued mochi wrapped in marinated cherry leaves. Along with the food, they savor these first releases from sake producers’ winter brewing. Namazakes, in this way, announce springtime, and they do it with gusto.

Bold flavor, mouth-coating texture, and, often, booming alcohol — “namazakes kind of shout at you, which is great,” says Padilla. “They just blow away the subtlety of other sakes.”

That’s because, when you open a bottle of namazake, it’s the roar of a crowd you’re letting out. Unlike most sakes, which are pasteurized, usually twice, to render them stable for shipping and storing, namazakes are alive with microorganisms. All those critters bring liveliness to the brew.

Springtime namas tend to be ginjo sakes, brewed from rice that is polished to at least 60 percent of its original size. They’re full of fruity, flowery flavors like melon, banana, and honeysuckle. Many of them are genshu, or undiluted, so they’re more potent than pasteurized sakes. The best ones balance sweetness with acidity; they finish clean and brisk. Though you might find them poured in U.S. sushi bars this time of year, they’re better suited to meaty, fatty picnic foods like prosciutto, cold pizza, and fried chicken.

As Sake Discoveries’ sake sommelier Chizuko Niikawa Helton says, “Springtime namazake is like Beaujolais Nouveau.” It’s meant to be drunk young, stored cold, and finished quickly, as the microorganisms inside it gallop through unpredictable changes over the course of a few days.

Yet, it wasn’t a seasonal nama that Padilla and I were enjoying. We were sipping the sake that he calls his “eye opener” — the first bottle that showed him an entirely different dimension of unpasteurized sake. Called Fragrant Jewel, it came from the 124-year-old Kidoizumi Brewery in Chiba, on Tokyo Bay. It had been produced using a proprietary version of a traditional brewing technique called yamahai, which involves moistening and heating the yeast starter for sake, then waiting for lactic acid to form. Today, most breweries simply add commercial lactic acid. But Kidoizumi uses a particularly hot version of yamahai, which results in a starter rich in the lactic and amino acids that bring intense umami notes and a robustness to the sake.

Chocolaty and mushroomy, Fragrant Jewel is part of a small but growing category of namas meant for aging. Many of them are imported into the States by Yoram Ofer, who is a bit of a cult figure in Japan. In the dark, serene confines of his Kyoto bar, Yoramu, the Israeli ex-pat pours funky, earthy namazakes that he ages himself — some at room temperature.

“I like sakes with flavor,” Ofer told me. “Deep, complex, balanced, interesting, innovative — that is the sake I like.” Though he doesn’t favor any particular brewing style, the type of nama that Ofer prefers is often achieved through traditional methods. Besides yamahai, that might mean the even older technique, kimoto, in which the yeast starter is beaten with wooden pools to bring on the lactic acid. It could mean polishing the rice to much less than ginjo percentages to leave its earthiness intact, or foregoing the typical charcoal filtration. All of these methods boost acidity and umami.

One of a handful of bar owners who age their own namas (Asakura, a short walk from Yoramu, is another), Ofer has influenced breweries like Kidoizumi to hold back namazakes before releasing them. Often announcing themselves with “kimoto,” “yamahai,” or a high rice percentage on the label, these bottles might come to market with several years of age on them, and if you buy a few and put them away, it’s fascinating to see how they evolve over time — peaking and ebbing like fine wine.

They bear little resemblance to springtime’s ginjo namazake. Yet, both styles have charms worth exploring. You can do that at a bar like Rule of Thirds, where Padilla features 20 or so namazakes at any one time. Or you can order them through online shops like Namazake Paul. Proprietor Paul Willenberg used to be a sommelier, but working at Portland omakase restaurant Nodoguro, he became a namazake disciple when he found that “the forward flavors really made everybody’s eyes just pop when they tried it,” he says. “It was unlike anything they had had before.”

After a year of lockdown monotony, what more could you want from a sip than something entirely new?

Five Namazakes to Try

Fukucho ‘Moon on the Water’ Junmai Ginjo Namazake

Bottled right off the press by Miho Imada, one of Japan’s few female tojis, this bright, juicy, springtime nama has a Margarita-like appeal. Think: Makrut lime and agave syrup. Luscious texturally, it opens with a touch of effervescence and finishes with a milky acidity. “It’s ginjo turned up to 11,” says Willenberg. Pair it with barbecued ribs. $38/720ml.

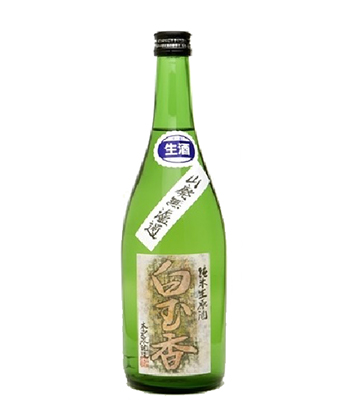

Hakugyokko ‘Fragrant Jewel’ Junmai Yamahai Muroka Nama Genshu

Warm-fermented to encourage its umami-driven ageability, this rich namazake boasts a Raisinet aroma and an earthy, toffee flavor akin to candy cap mushrooms. The sherry-like tones are balanced, though, by melon notes and a palate-cleansing finish. Charcuterie and aged cheeses are worthy accompaniments, though it’s also terrific with a bowl of coffee ice cream. $35/720ml; $75/1.8L.

Nagaragawa Sparkling Nigori Sake

What a surprise this cloudy, unpasteurized sake is! Whereas most nigoris are syrupy sweet, this one has a seltzer-like crispness. Produced to the strains of classical music to promote vibrant tank fermentation, then re-fermented in the bottle, it offers a spirited bubble, yogurty nose, and fruity overtones — all undergirded by a Cel-Ray-esque savoriness. Bone-dry on the finish, it cuts through the fat of roasted almonds, prosciutto, or blue cheese with honey. $11.99/300ml, plus shipping

Kikusui Funaguchi Ginjo Nama Genshu Aged Red

This little red can is designed to be grabbed from a vending machine and paired with a train station bento box. But it’s also great for a cookout, particularly if you’re grilling steak. A weighty body and golden hue bespeak its year of aging, as does its bread pudding flavor. Think: sourdough, mocha, nuts, whiskey. Its packaging means “you can freeze it and make a slushy,” says Niikawa Helton. Just be careful: At 19 percent ABV, it sneaks up on you. $9.99/200ml.

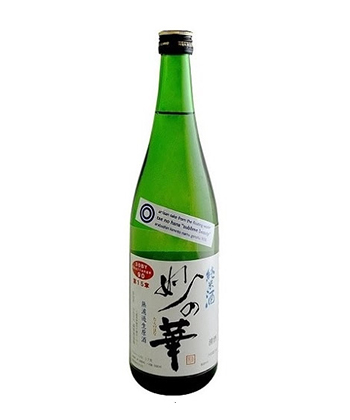

Tae no Hana “Sublime Beauty” Arabashiri Kimoto Junmai Muroka Nama Genshu

Fourth-generation female brewer Rumiko Moriki polishes the organic rice for this nama to only 90 percent to leave much of the grain’s earthy proteins intact, and her kimoto yeast starter is rich in amino acids. The result is a creamy mouthfeel and tropical charisma. Laffy Taffy aroma yields to a brûléed pineapple taste with herbaceous undertones and a drying, acidic finish. Unlike many namas, its flavor only seems to intensify and clarify after several days opened. $33/720ml; $65/1.8L, plus shipping