The year was 2005. I was 26 years old, living with two roommates in Hell’s Kitchen. Woefully underemployed as an aspiring screenwriter (spoiler alert: it never worked out), I had a taste for the craft beer that was finally emerging in New York City, and the impending cocktail revolution and bourbon renaissance, too, but I mostly liked to stretch my drinking dollars as far as possible. It wasn’t always easy to figure out how.

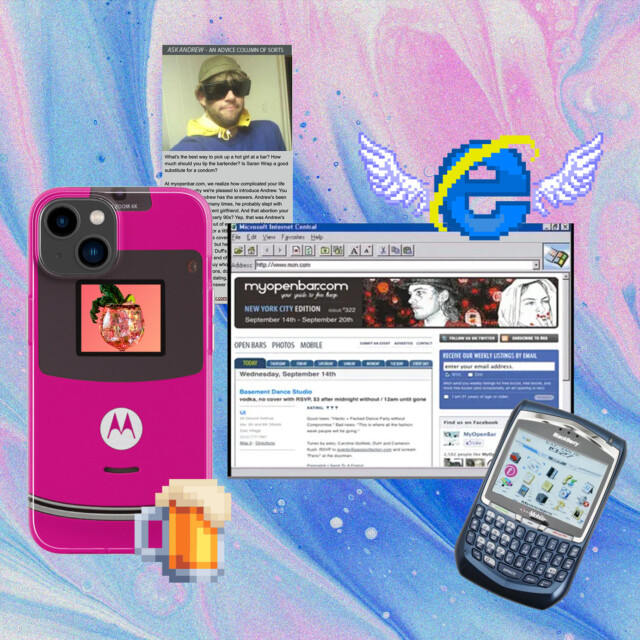

Remember, this was an era right at the brink of social media. Texting was still done via the T9 technology on flip phones. To research bars and restaurants we would literally thumb through guidebooks or print magazines. Recommendations for where to get sloshed for cheap most often came through word of mouth or people on the street passing out fliers.

That was until there arrived a website and accompanying email list that literally told screw-ups like me where we could drink for cheap or even free each and every evening:

An email from August 2005 I’m somehow still able to retrieve lists some events for that week:

“The Trash Bar

Williamsburg

The Deal: 9-10pm. Open well drinks bar with $5 cover, free tater-tots with any drink order.”

“LaGuardia Grill

West Village

The Deal: Free Wine! All F*cking Day! Always!”

“Still

Flatiron/Gramercy/Union Square

The Deal: 6-8:30pm. $10 all you can drink, includes Bud and Bud Light Drafts, all well drinks, cosmos, appletinis, as well as 1/2 priced appetizers.”

“Bar 4

Park Slope/Prospect Hts

The Deal: 6pm-3:30am. $15 for unlimited PBRs and Yeunglings (sic).”

Unlimited mixed drinks. Cheap Cosmos. Free (f*cking!) wine. Nine-and-a-half hours of open bar drinking.

It seemed too good to be true.

But, for anybody living in New York during the mid-aughts, MyOpenBar.com was a boozy lifeline.

The Impetus to Get Smashed

Seva Granik and Rob Hitt were struggling musicians living together in Williamsburg in the early aughts.

“He was Jewish and I was Jewish. And not to get into stereotyping here, but we were definitely looking to save some money, mainly because we didn’t have any,” recalls Granik, who was born in Uzbekistan. “Our rent was like $400 and still we found it difficult to make ends meet. But the impetus to go out and get smashed every night was very high on the to-do list.”

With Williamsburg still in the throes of development and gentrification, that mainly meant looking for hotspots in downtown Manhattan. The two men somehow figured out that, on most nights, various beer, liquor, and wine brands would use hour-long open bars as a sort of marketing ploy.

“Strangely enough, though, those were kind of empty and not super popular,” Granik says. “But that was exciting to us.”

Granik and Hitt started hitting these free happy hours early in the evening; soon enough, they had a crew of friends joining them. At the time, Granik had a Blogger account where he would recount his previous evening’s misadventures to a small group of readers. Eventually, that morphed into him posting about the free events he planned to attend that coming evening.

“It got super popular just through word of mouth throughout our little community of musicians and artists and just kids — lots of girls, some gays back then,” Granik says. Because of his background as a musician, he was already well connected to the denizens of nightlife, bartenders, bar owners, promoters, and the like, who knew of the events and daily drink deals that might excite New York’s growing 20-something class. “Then, at some point, I just recall making a tiny bit more effort to do the research.”

“Back in the day it was MySpace and My everything. So we were My Open Bar.”

His readership was expanding rapidly and Hitt suggested they formalize it. Granik had experience in web design from a false start of a career building intranets for financial institutions in a pre-9/11 New York. Hitt was already skilled at marketing and promotion from managing his own little record label he had founded in 2003, I Surrender Records.

They added Jason Fried, a math whiz and Berklee College-trained musician, who improved the website and then became its CTO. Granik’s ex-girlfriend Becky Smeyne was the final piece of the puzzle as content editor, helping craft the website’s snarky writing that was emblematic of the era.

“At that point we were like, OK, well, we need a name. Back in the day it was MySpace and My everything,” Granik says. “So we were My Open Bar.”

The Least Common Denominator Bar-goer

In half a year, MyOpenBar.com gained 3,000 subscribers to its weekly e-blast that listed around a dozen places offering free (or exceedingly cheap) drink deals. Within a year, the subscriber count reached 18,000 and listings were happening daily.

Almost instantly the site began to receive press. The New York Times called it “a kind of Zagat guide for freeloaders” while the New Yorker said that any promoted event was packed with people solely there for free beer, which was often Red Stripe.

“Overnight these beer, liquor, and wine brands wanted to talk with us because, back then, I’m sure you recall this newly anointed demographic: hipsters,” Granik says. “The Brooklyn hipster was all the rage. Marketing, promo, magazines, brands, and products were chasing after them like crazy because they thought that was like the second coming of Christ.”

Granik, long embedded in the hipster scene, knew it was all bulls*it, but he was happy to swim the “mad river of money flowing toward New York.” He received cases of free product: Reyka Vodka, Svedka Vodka, Red Stripe, Bass Ale. He and Fried began entertaining alcohol brands in the city and flying out to places like Anheuser-Busch’s brewery in St. Louis to try and start partnerships and bring in more loot for their company.

Still, Granik tried to keep the events cool and as non-corporate as possible. He told The Times he was “exploiting corporate greed for the collective good.”

Eventually, however, the Murray Hill bros, the NYU kids, and other decidedly non-hipster types like, well, me started invading events. Granik didn’t exactly care, but he began to rate upcoming open bars on a sliding scale of quality (one to five wine glasses), praising events that actually had a cultural or artistic purpose and might attract cool people as opposed to those that were just “appealing to the least-common-denominator bar-goer” who simply wanted to get wasted for free. (The founders always insisted that people, at least, tip a buck or two per freebie.)

Soon, bars and restaurants started reaching out to My Open Bar, clamoring to get their events listed on the site. If it was a good deal Granik would list it, though that didn’t necessarily mean he endorsed it. From the get-go, Granik and Smeyne had editorialized on the listings. But as highly corporate events became more ubiquitous — as the fans open bars began attracting became more deployable — the snark quotient upped even higher.

“Who goes to the East Village anymore?” read their comment on one listing. “Two hours of free top-shelf vodka on a Wednesday night draw a thin line betwixt an asset and a liability (sic),” read another. Then there was one for the Happy Ending club on the Lower East Side: “Being inside you makes me feel like a 40-year-old hooking up with a spring break coed in South Padre.”

In December 2007, a little over two years into My Open Bar, and two months after the Dow Jones hit an all-time high, significant turbulence in financial markets meant the world was about to change in many ways.

A Viable Business

“The recession has definitely increased growth. We’ve seen it for at least the last four to five months,” Fried told the Daily News in 2008. (He also told the tabloid he would drink anything for free save Sparks, a saccharine sweet alcoholic energy drink that pre-dated Four Loko.)

If the Great Depression had, unfortunately, happened during the tail end of Prohibition, those who were down on their luck could still find plenty of opportunities to illicitly and cheaply imbibe. By contrast, there was no problem finding legal places to drink during this so-called Great Recession; many people just lacked the money to do so.

“The bad economy is doing nothing but helping us,” Granik told The New York Times in 2009. “We’re probably the only company we know of that’s doing very well because of the downturn.”

By January 2009, My Open Bar had 30,000 subscribers in New York City and 19,000 more among five offshoot cities (Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Miami, and Honolulu). The company had 30 employees on the payroll and a “fancy-ass office” (according to Granik) in the same landmarked Union Square building that Andy Warhol used for his Factory in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The site had also attracted free-spending sponsors like American Apparel, had partnered with Blackberry, was throwing subscriber-only concerts with local bands like Apes and Androids, and holding events at big-name festivals like South by Southwest.

That month, The New York Times again covered the website, reporting on an event at the Slipper Room, a Lower East Side club with red velvet-lined walls that was serving free Drambuie, a honey-and-herbal-flavored blended Scotch, all night long. “There’s no amount of free liquor that would help me acquire a taste for Drambuie,” remarked one attendee who was, nevertheless, drinking it up. In fact, the event had attracted a line snaking around the block. “Normally I could not afford this fine liqueur,” another attendee said as she took a sip of a Drambuie fizz.

Though the website was now in its fourth year, and the world now in the full grips of recession, it was attracting more bar listings, more brand promotions, and more readers and subscribers than ever before. Alcohol, it seems, is recession proof, as we are so often told.

Granik was beginning to butt heads with his partners, though. After four years of doing My Open Bar, he was still most interested in keeping things DIY and punk rock; they were interested in actually making money at a time when so many other New Yorkers were struggling to do so.

“They were like, ‘This is a viable business. What are you guys doing?’” says Granik, who notes that My Open Bar was pulling in around $1 million per year at the height of the site’s popularity.

Granik was losing interest, however; now in his early 30s, now tired of drinking every single night, and now ready to move onto other ventures. (Today he’s a noted lighting projectionist and events producer, and has been an adjunct professor at NYU; Hitt would go on to launch the viral Bodega Cats empire, still plays in a rock band, and works as a web developer.)

The internet was going through a tidal change and so was New York City nightlife. The smartphone era had arrived with the iPhone in 2007. Facebook and Twitter had become dominant forces and there were now countless ways to quickly promote bars and brands online. New York, meanwhile, was about to enter a new phase of more cultured drinking with an explosion of craft beer bars and breweries, natural wine spots, and iconoclastic cocktail dens like Death and Co. and PDT, both of which had just arrived on the scene.

Competition arose in the free drinks space as well. There was now BoozeParty.net, which offered a similar summary of where to drink for free or cheap every day. DrinkDeal.com listed happy hours by day and time, while the HappyHoured smartphone app did it via geo-location. MurphGuide offered a stripped-down summary of where to drink cheaply, or freely, every day, and PulseJFK tweeted out drink deals on the daily.

Eventually, though, everyone realized open bars weren’t exactly a great business plan for any one involved. Filling a bar or club with freeloaders didn’t bring in revenue. Giving away all this free product caught up with the brands, too, which were now just as affected by the recession. Suddenly the cash began to dry up for all involved.

Say Granik: “That’s when brands realized that they were just chasing a demographic that a) didn’t have any money and b) didn’t have any pull.”

As for me, by then, I had just started my career as a booze journalist — and the free drinks have never stopped flowing.