Some stories don’t need to be embellished. These are the tales whose raw truth is fascinating on its own merit — mainly because what really happened doesn’t seem plausible. In the wine world, nothing fits this bill quite like the account of how the United States came to the rescue of French vineyards in the late 19th century. It’s a story that sounds far-fetched on the surface, particularly from the perspective of the modern wine drinker. After all, the U.S. didn’t have a world-renowned wine scene in the 19th century — certainly not one on the level of France.

Considering that it took the Judgment of Paris in 1976 to shift France’s (and the world’s) attitude toward American wine, the fact that U.S. vines could have saved the French industry is nothing short of ironic.The story gets even more bizarre when you dig into it and find out that rootstocks from Missouri and Texas are involved, and both states have a role in stretching reality into a tall tale.

If you know enough about the story to do a Google search on “Missouri rootstock and French wines,” you’ll get a wealth of stories that solely concentrate on Missouri’s angle without a hint of a Texas reference. If you replace “Missouri” with “Texas,” the opposite occurs, with articles making vague references to “some states” failing in their attempts. Unless you dig into the story, it’s entirely possible to entertain the notion that Missouri “saved” French wine without ever knowing that Texas was involved — and vice versa. The states have gotten so good at solely telling their side of the story without acknowledging the other state’s handiwork, it nearly feels like there’s some sort of weird regional rivalry going on. Unfortunately, these incomplete accounts have given rise to their own mythos that ends up obscuring what really happened. “The way Missouri and Texas tell the story isn’t necessarily fiction,” explains Nathan Held, director of strategy for Stone Hill Winery in Hermann, Mo. “But it does contain lots of half-truths.”

Understanding this story in full — not to mention why Missouri and Texas don’t really bring up each other when the story’s told — requires quite a bit of context. And it all starts with a nasty little bug called phylloxera.

The Bug That Attacked France

Phylloxera is an aphid-like insect that feasts on certain types of roots and leaves. They didn’t show up in France until around the mid-19th century, when they more than likely arrived from the United States. This alone adds a weird layer to the story — the U.S. was the most probable cause of a problem it would eventually help resolve. However, some circles believe America’s role in the origin story was inadvertent at best. “Some theorize the French brought the American vines into their country,” says Held. “In this case, the vines were most likely transplanted as ornamental grapevines for the French elites.”

When the pests did arrive, they wreaked havoc on a massive scale, wiping out between 40 and 50 percent of French vines in an unsavory phenomenon now known as the Great French Wine Blight. Nobody knew the cause of the mass destruction as it unfolded, a mystery propelled by phylloxera’s near-microscopic size and its penchant for sucking the vines’ sap at their roots. All that was initially tangible was the spread of withering vines and destroyed vineyards year after year. The bugs were pinpointed as the root of the issue by French botanist Jules Emile Planchon in 1868, and their discovery was enough to whip American scientists into a frenzied research effort. “Everyone was freaking out about needing to go to the mat for France and finding a way to help them out,” says Jessica Dupuy, author of “The Wines of Southwest U.S.A.” “They slowly started to realize that the U.S. had phylloxera but didn’t have the phylloxera problem, and figuring out why would help them figure out a solution.”

Because the state of technology at the time prohibited efficient communication between scientists, the process to find a solution somewhat resembled a race. One of the scientists involved in this pursuit was Missouri’s state entomologist Charles Valentine Riley, who observed that phylloxera in Missouri didn’t attack vines at their roots. That led Riley to theorize that Missouri rootstocks — the base and root part of the vines — could be grafted onto French vines and thwart the phylloxera’s rampage. Equipped with this theory, Riley reached out to Planchon directly, and the two collaborated on an effort to stop the insect onslaught. The theory proved to be correct. By 1873, the project to defend French vines from phylloxera was in full swing, aided by grafts cultivated by Missouri viticulturalists.

Where Missouri Ends and Texas Begins

This is usually where the Missouri narrative stops, occasionally with a self-congratulatory pat on the back. This also gives the story a dramatically altered ending, which is something that even some in the Missouri wine scene find problematic. “People need to put the ‘Missouri saved French wine’ narrative to rest for the story to be told correctly,” explains Jon Held, president of Stone Hill Winery. “Some folks believe the way it’s told is great, and they look at me cross-eyed when I tell them it’s not right. However, the truth is so much better because it helps you better understand the science of the whole story.”

But this truth and its science dramatically soften Missouri’s stance as the tale’s conquering hero. While Riley’s efforts were instrumental in getting the process started, his strategy didn’t pan out as intended. After initially thriving, the Missouri rootstocks started to die off, as they couldn’t handle France’s chalky, alkaline soils in the long run. As their effectiveness began to decline, there was concern among French wineries that this fix would end up being a temporary boost, and that France would soon be under the swarm of phylloxera yet again.

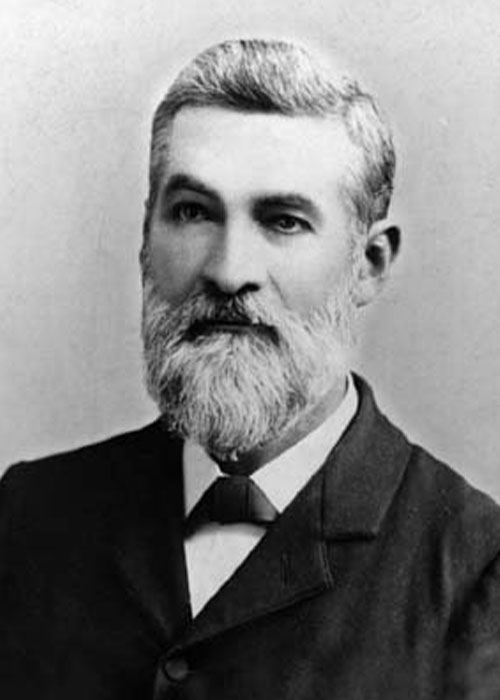

Enter a horticulturist named Thomas Volney Munson. While not a native Texan — he originally hailed from Illinois — he’s colloquially known as the Grape Man of Texas due to his extensive work with Texas grapes. In the 1880s, a decade after Riley’s work in Missouri, Munson determined Texas rootstocks could also neutralize phylloxera’s powers. Better yet, this species of vine could handle the nature of French soil when grafted to vines.

Eventually, French wineries added Texas rootstocks to their suffering vines, the phylloxera problem waned, and varietals like Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, and Merlot were spared from long-term devastation. Munson’s efforts have since earned him plenty of justified praise from Lone Star State wine lovers and historians in the know — although some do feel his role gets a bit inflated. “Munson wasn’t some genius that came out of nowhere to proclaim, ‘I’m going to save France!’” Dupuy says. “He already knew where to get things started.”

A Story of Self-Promotion

There is no odd interstate rivalry between Missouri and Texas wine. The mutual silence between each other’s involvement is purely practical and pragmatic. Missouri’s narrative lops off the unfortunate ending to its efforts. The Texas version boosts Munson’s heroic gravitas. In both cases, John Held says, “The story is primarily used by wine programs as PR. Each state really just uses it to try and promote their own scene.”

Still, some feel the two states effectively splitting the full tale into two accounts built on incomplete truths does more harm than good: “If Missouri and Texas would tell the story in full, it would make it easier to tell,” says Nathan Held. “They’d still be able to lay claim to it, and it would probably gain a lot more traction and reach a broader audience, which would be a great thing. People don’t realize how important Midwestern vines once were.”

This importance isn’t completely obscured. According to Nathan Held, France honors the story through a pair of statues. However, these statues also inadvertently separate the narrative: One of the statues honors Riley, while the other statue honors the Americans who helped resolve the issue, including Munson. Vive la différence.