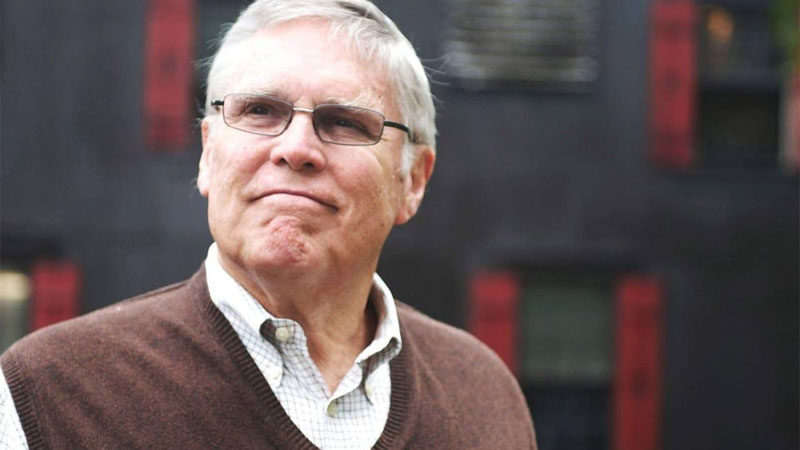

The summer he learned to drive, long before he became president of Maker’s Mark and godfather of the bourbon business, Bill Samuels Jr. became something of the first employee of Harland Sanders, a man now known to the fried-chicken-eating world as The Colonel.

“June 1, I had just got my driver’s license,” Samuels later recounted. “And whoaaa, I was excited.”

When he drove home that day, he encountered Sanders, a family friend and gin rummy partner to Samuels Sr. The Colonel had stopped in for the night while scouting the towns of central Kentucky for new business partners. Sanders asked young Samuels what his plans for the summer were.

The short answer was work. In the Samuels’ household, the end of the school year and the beginning of summer meant that he would soon be mowing lawns and painting fences in the heat.

That day, however, Sanders made him an offer that would grant him reprieve from those mundane, allegedly character-building chores. Samuels could drive him around, The Colonel said, and be his assistant as he traveled the length and width of Appalachia.

Earlier that year, Sanders had shut down his locally beloved fried chicken cafe in Corbin, Ky. The route of the new Interstate Highway System bypassed his kitchen, reducing his life’s work into a property on a neglected road sold for a loss at auction.

Rather than retire, Sanders took his famous fried chicken recipe and hit the road looking for family restaurants that might add his chicken to their menus. Samuels accepted The Colonel’s offer and, though Sanders never actually paid him a dollar, for a short while the young spring chicken was put under his master’s wing. Samuels learned the dark art of salesmanship and small talk from one of its most legendary practitioners.

What Samuels saw riding shotgun with Sanders would not only amount to lessons in strategic schmoozing of the old-boy variety, it offered total immersion into the timeless and wholly irrational tradition of specialized craft.

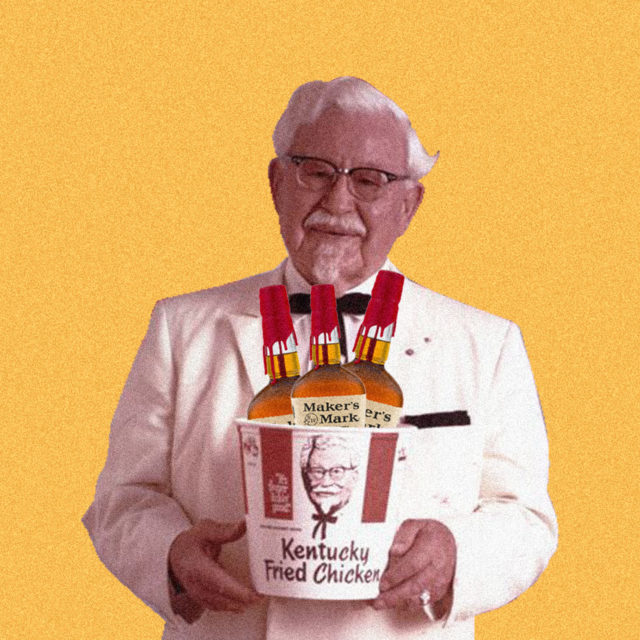

Several decades later, an old photograph of Harland Sanders grinning in a white suit in front of a Kentucky Fried Chicken is one among dozens of antiques and artifacts inside the handsome, mahogany conference room at the Maker’s Mark distillery in Loretto, Ky.

Without even trying, these assorted heirlooms delineate an intimate league of Kentucky craftsmen. Their work created national icons — horses into thoroughbreds, maple and ash into Louisville Sluggers, fried chicken into KFC, and whiskey into Kentucky bourbon.

“My grandfather’s best friend was Jim Beam,” Samuels tells me. “Pappy [Van Winkle] gave me my first drink as a 12-year-old.” He believes this community of “tinkerers” helped develop his father’s taste and vision.

“What is it about Kentucky?” he wondered aloud. “Now, I can’t speak with authority really outside of bourbon. I did have the good fortune of knowing a lot of these people, I lived next to ‘em, and I did know Colonel Sanders pretty well and loved him. Tinkering was a big piece of it, and you know you can always look back and connect dots. It’s hard as hell to look forward and connect ‘em. The common thread, looking back, is that they were all craftsmen, they were all focused on product. And if you ask ‘em about a marketing strategy, they would say, ‘Well, if we make shit that tastes good…’”

That was The Colonel’s guiding truth, Samuels explained. It had also been the philosophy behind Maker’s Mark.

“Dad had no commercial sense at all,” he went on. “It was all about what’s inside the bottle. Matter of fact, most of the fights that mom and dad had were over the fact that he was going to bankrupt ‘em because the stuff was just gonna stay in the barrel and hadn’t given much thought to commercializing it. So he was probably the purest non-entrepreneur to ever create an industry.”

The Samuels family can trace its Kentucky and booze-fiddling roots back centuries, but for Bill Jr., the expertise had really started with his father. “He went off to do one thing, which was make better whiskey than his ancestors did,” Samuels explained. “’Cause we came to Kentucky with my five-great-grandfather’s 60-gallon copper still from Pennsylvania. My four-great-grandfather mustered out of the Revolution … took his father’s still, came to Kentucky. That’s what we started with and that was 1784. And we made shitty whiskey for the next 170 years. Made a living at it!”

To this day, Samuels attributes the early successes of both Maker’s Mark and Kentucky Fried Chicken to the quixotic (and perhaps pathological) devotion to keeping the sanctity of their products intact. In his travels with Sanders, he would repeatedly see The Colonel’s supernatural wrath upon any cook or mom-and-pop operator who dared to screw with his recipe.

After one monumental scolding, young Samuels confronted Sanders about his temper. “Matter of fact, I fussed at him,” Samuels said. “Can you imagine this 16-year-old, fussin’ at the guy who, in five years, was gonna be the most famous living person in the world? I told him, ‘I thought that was a little over the top.’”

The Colonel got outraged, Samuels recalled. “He said, ‘It wasn’t neither.’ And I said, ‘How come?’ He said, ‘Well, we won’t have to do it again.’”

“And the word got out: Don’t fuck with The Colonel’s process. … ‘Cause he was a true maniac for doing it right. And I always respected that. I’d say that was the main learning from him for me.”

In the 1970s, Samuels took over Maker’s Mark and shepherded it through the unprecedented whiskey boom before retiring an industry legend in 2011. Prior to relinquishing charge, Samuels’ father had delivered him one imperative: Don’t screw up the whiskey.