The 1995 Keanu Reeves romantic drama “A Walk in the Clouds” wasn’t actually filmed in Haro, Spain, but it absolutely could have been. Leisurely ambling the city’s cobblestoned streets, in the rolling hills of the Ebro Valley, you half expect to turn a corner and bump into a production team wrapping up a day of filming.

Haro is located in La Rioja, where crimson-hued Tempranillos flow easy and reign supreme. It’s about a three-hour bus ride from the sprawling metropolis of Madrid, but it looks as though time stopped somewhere in the 16th century. Narrow, sun-blanched streets wind through the city center, and medieval churches sit nobly on shimmering green hilltops.

In this place, tradition is prized over modernity. The old ways of doing things are championed above the new.

“Our winemaking process has [always] tried to respect nature and to manipulate grapes and wines in the cellar as little as possible,” says Maria López de Heredia, fourth generation winemaker at R. López de Heredia Viña Tondonia winery, the oldest family-owned bodega in Haro.

Maria and her sister, Mercedez, run the day-to-day operation of the vineyard. The López de Heredia family has been producing Tempranillos since the 19th century, using the same viticulture and viniculture methods. The winery has only ever sourced grapes from its own vineyards, and works in harmony with nature, wasting as little as possible and reusing materials whenever practical.

“Being at peace with our surroundings is a part of our family character. In order to love nature, you have to observe it and understand it. And when you understand it you learn to follow and respect it,” Maria says.

For this family-run business, sustainability isn’t a trend, it’s a way of life. López de Heredia’s philosophy employs a simple, old-school mantra: Waste not, want not.

The idea of working symbiotically with one’s environment — and being less wasteful as a result — isn’t on its face revolutionary. In various fields, environmentally friendly practices like upcycling are in vogue. In the wine world, biodynamic and organic farming is increasingly popular. Reuters recently reported that, although organic wine is still a relatively niche category, consumer demand is growing. Demand is set to increase to 1 billion bottles by 2022, in stark contrast to the 676 million bottles sold in 2017.

In Haro, decades-old bodegas have started returning to the old ways of doing things, à la López de Heredia. It is often more labor- intensive, but gentler on the land, too.

“Sustainability is not an option, it is a way of feeling, doing, and thinking indispensably in quality projects,” says Valvanera Valero, the director of marketing and communications at Bodegas Gómez Cruzado, a winery just down the road from López de Heredia. “[Sustainability] is an unwavering commitment for any [wine producer] that wants to influence his or her sector and win the preference of the consumer.”

It’s easy to see how producers can throw around words like “organic” or “sustainability” as nothing more than a marketing ploy. But Haro wine producers are embracing environmentally sound practices as a means to ensure the quality of their wines as well as the economic longevity of their bodegas. Gómez Cruzado, for example, put measures in place to ensure a reduction of the use of sulfur while paying close attention to its energy and water waste.

R. López de Heredia Viña Tondonia, however, stands in a class alone when it comes to figuring out how to use every bit of energy and material that goes into its winemaking process.

The process begins in the fermentation pavilion, which has 72 impressively large fermentation tanks, some of which are as old as the vineyard itself.

After dancing around with what Maria calls “indigenous yeast” in oak vats for a bit, winemakers separate the juice from the grape skins by a simple filtration process used by Don Rafael, Maria’s winemaker father. Don Rafael tightly bundles the grapevines and holds them in front of the spout emptying out wine. Later these same vines are repurposed as fuel by the winery to grill meats and vegetables.

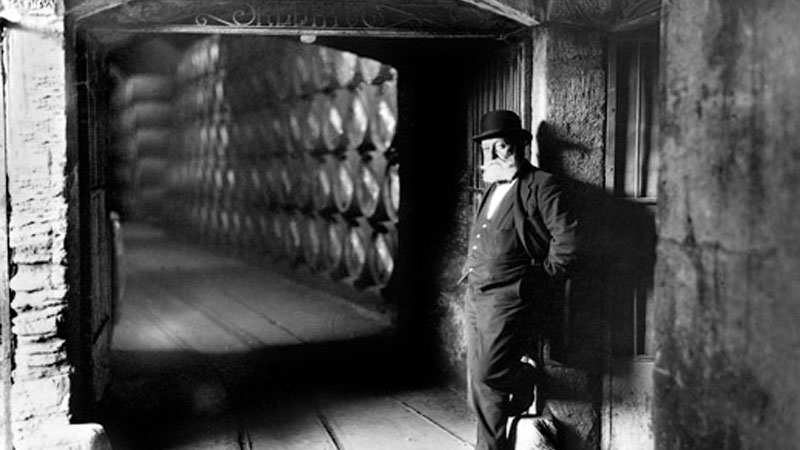

After filtration, the wines head downstairs to the cellar and into over 14,000 handmade American oak barrels. Getting to the cellar requires a walk down impossibly dark and perilously steep stairs about 50 feet below ground. This dimly lit space is heavy with the scent of musty wine-seeping wood, and naturally cool due to its proximity to the Ebro river flowing nearby.

The excavation of the wine cellar, a feat that started in 1904 and spanned several generations, yielded tons of quarried stone that was later used to build the family estate. It sits atop the underground cellar and next to the tasting rooms to this day.

Here, bottles from as far back as 1885 rest on their sides, covered in naturally occurring mold. It helps attract and maintain humidity, and creates climate-controlled conditions for the wines aging in both barrels and bottles. The mold blankets the damp walls, floors, and ceilings — and also attract spiders, as evidenced by the lacy webs strung overhead. This too has a purpose: The mold protects the bottles and the spiders protect the mold. Ecological balance in action.

On the other side of this room is the cooperage, which has been in operation as long as the winery. In this oppressively hot room, a literal nightmare for those afraid of bugs, spiders, and pests of all sorts, generationally trained wood experts align planks of Appalachian oak to create barrels. The barrels are used to age the wine for three to 10 years, depending on the grape, vineyard, and vintage.

Barrels that can no longer be used for wine are broken down and either used as wood to help char the insides of new barrels, or repurposed into furniture such as chairs, tables, and the planters that decorate the visitors entrance and small cafe on site.

“We believe that being environmental sustainable or organic should be the rule, and not the exception. We do everything that anyone can do but, again, I believe that what makes us a bit different is that we have done them for 142 years, whether it’s trendy or not,” Maria says.

“Craft,” like “sustainability,” can seem like a marketing buzzword. But there’s something to be said for taking pride in your work. At R. López de Heredia Viña Tondonia, it’s evident in every thoughtful step of the process.