“Krista is one of the most genuine and dynamic people I’ve ever met, and that translates directly into her winemaking,” Marissa Ross, writer and wine editor of Bon Appetit, says.

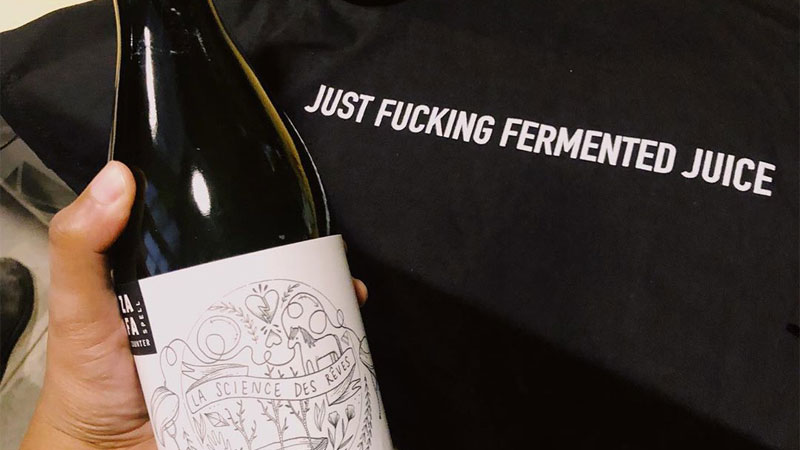

Krista Scruggs launched ZAFA Wines in 2017. Since then, she has been releasing genre-busting natural wines in Vermont (and a few from a side project in Texas), and taken the natural wine world by storm. All for making “just f*cking fermented juice,” as Scruggs calls it.

“She is intentional, daring, and confident in her vision, while having the humility to allow the fruit and the wines to express themselves,” Ross adds.

Many winemakers talk about honoring fruit, but Scruggs’ fearless approach is unprecedented in modern wine. Rather than create vintages of a core lineup year after year, Scruggs produces entirely different wines every season, based on what fruit is behaving which ways in the field and winery. She provides context and an almost biographical narrative for her wines, sharing the story of why each wine exists; and, furthermore, why it will never exist quite the same way again.

In 2017, she made seven wines: Jungle Fever, Anchors Aweigh, Against All Odds, No Love Lost, bam·boo·zle, Maximilane, and Naive Melody. Only one of them, Jungle Fever, is returning under the same name next year. “I want it to be part of my ethos as a winemaker that I’m not trying to recreate anything,” Scruggs says.

Her personal biography is reflected in her releases, and she believes any fermented fruit juice, be it grape or apple, constitutes wine. In 2017, for instance, her range included “Naïve Melody,” a still cider. Scruggs originally intended to make it in the Champagne method. She had just finished her work with Deirdre Heekin and Caleb Barber of La Garagista — her first Vermont winemaking job and mentorship — and was driving her unfinished projects to her new space with Shacksbury.

As she drove down the hill, the cider “woke up” in the heat wave, starting a secondary fermentation, she says. Upon arrival, she tasted it, and “it had grown up.” Malolactic fermentation had started, and she liked where it was going. So, she thought, “I’ll f*cking bottle it.”

“If I hadn’t had to move it, it would be a different wine,” she says. “I think it’s beautiful that the wine helps tell that story. I was undergoing a change as it was.”

Colin Davis is the co-founder of Shacksbury and one of Krista’s partners at Co Cellars, an urban winery in Burlington. “It’s an interesting way to think about production, especially for natural winemakers,” Davis says. “So much of the process is hands-off that trying to hit the same target every single year is ….”

“… Is kind of contradictory,” Scruggs chimes in. “As long as ZAFA’s consistent in making something quality, that I want to drink and that other people want to drink every year, each label doesn’t really matter to me,” she says. “My job as a winemaker is to honor the fruit of that year in the vineyard, and in the cellar to usher in and honor what is going on. Terroir is all those variables. My job is to make decisions that honor it each step of the way.”

Co Cellars in Burlington is an important part of the ZAFA vision. “This is the first and only urban winery in Vermont, and people can come in and see the process at any time,” Scruggs says. “I think the more educated the consumer is, the more they’ll be demanding good wine.”

Being a vigneron — a grower of grapes, as well as a winemaker — is important to Scruggs. The opportunity to own and work her own land is the reason why she came to Vermont in the first place. She was born in California, worked on the corporate side of wine, did a harvest in France, then made a plan.

“I knew who Deirdre Heekin was and knew that she was an example of a true vigneron,” she says. “I heard she’d be at Ordinaire, my local wine bar [in Oakland, Calif.], so I went and met her and asked to do a harvest with her. Four months later, I was flying out to Vermont to harvest with her, and got a job offer soon after. It was the easiest decision of my life.”

Things moved more quickly than either of them anticipated. “Deirdre knew what my end goal was, and we had a five-year plan,” Scruggs says. “We had no idea that it would happen in two. Everything that I wanted has truly come to fruition, no pun intended.”

Vermont may not strike most as a wine destination, but for those looking to follow the vigneron path, it’s a natural fit. “There are few examples of vignerons in this country, and only a few places where you can make that a reality, because of land ownership and access,” Scruggs says. “When I got to Vermont, I knew this was it. I knew this was the place that I could do what I wanted to do. I told people what I came here for, and they said, ‘O.K., this is how we can help you.’

“I think everyone in this community has a similar story — you say what you want, and people help you make that happen. It’s part of why we make such f*cking amazing cider and wine. We’re not competing with each other. We understand that for us to rise that we have to rise together. That’s not the case everywhere.”

Scruggs now has 40 acres of land in Vermont’s Champlain Islands, 10 of which she’ll be planting this year. She looks forward to what she sees as the challenge of being more established, saying, “How am I still going to be creative if I’m getting the same fruit every year?”

She will cultivate grapes and apples, yes, but also pear, persimmons, and pawpaws. She wants to make a pear cider called perry —she says the perry made by Vermont’s Windfall Orchards is the best in the country — and sparkling kombucha.

“I was doing the not-fun side of winemaking — the invoicing and the office stuff — the other day and it gave me a chance to reflect on the price point I’m setting for my ciders,” Scruggs says. “I had a moment of worry, and then thought, ‘Why am I rethinking this?’ I’m not going to downsell the work and risk and time that went into making this, just because it’s made from different fruit that is equally valuable and takes just as long to grow.”

Heekin says she’s excited to see Scruggs spreading her wings and “embracing more of the old ways of growing wine. There is a focus on both the craft and intention of farming and attention and respect for the fruit in the cellar, letting the fruit and then the wine tell a story of place. Not only is this reminiscent of the wine of our past, but it is the wine of the future.”

Climate change is currently altering the terroirs of wine regions worldwide. Additionally, a solitary acre in Napa can cost up to $500,000; that same area will run you less than $10,000 in Vermont. Those curious about the future of winemaking in America are wise to look to places like Vermont and Texas.

“Her point of view, in life and in winemaking, I believe, will prove to be one of the most influential in modern American winemaking,” Ross says.