The island nation of Barbados is renowned for more than just Rihanna — the country is also home to a thriving rum industry that dates back to the 17th century. While many are familiar with Bajan rums — Mount Gay and Malibu being some of the most popular — few are aware of the early geopolitical developments that caused Barbados to become one of the Caribbean’s most prominent producers of the spirit.

The industry’s origins lie not with the English colonists who claimed the island under their crown, but instead with a mass migration of Jewish refugees. Fleeing persecution from the Portuguese Inquisition, these newcomers arrived with a valuable skill set that would soon spur rum production to heights previously unseen.

The Great Journey From Iberia to Brazil to Barbados

Before detailing the Bajan rum boom, it’s necessary to highlight the driving force that brought these refugees to Barbados in the first place: the Alhambra Decree. This royal mandate, backed by Spain’s Ferdinand II and Isabella I in 1492, sought to eliminate any and all Jewish influence from the Iberian Peninsula. While many Jews chose to undergo conversion to Catholicism, a large portion fled across the sea to seek out a more tolerant place to call home. For many Sephardim, the northeast shores of South America became a haven to live and worship freely.

Life for Jewish immigrants in South America was largely uneventful for the next few decades, until the geopolitical tides came to a sudden shift in the early 1600s. The Netherlands, a major seafaring power bent on spreading its influence, captured the Brazilian state of Pernambuco from Portugal in 1630. Dutch influence spread across the region until the kingdom owned a sizable chunk of South America, now referred to as Dutch Brazil. Dutch Count Johan Maurits espoused religious tolerance throughout the region, allowing Jews to worship freely. Finally, it seemed that this frequently persecuted group had found a safe place to settle.

Enter Portugal: The kingdom’s navy returned to Brazil with a vengeance, intent on reclaiming the land it had once relinquished to the Dutch Empire. In 1652, the Portuguese began an onslaught against the city of Recife, leading to one of the largest mass migrations of Jewish immigrants from South America.

“Though Jews were in Barbados from 1628, the first large wave came after the Sephardic community of Recife, Brazil, was forced to leave … after the Portuguese reconquered the area and reintroduced the Inquisition,” says Karl Watson, a retired senior lecturer in the department of history at the University of the West Indies Cave Hill Campus in Bridgetown, Barbados. “By 1654, a mikvah and synagogue were built in Bridgetown.” Once again forced from the lands that they called home, the Sephardim began a new life on the shores of Barbados.

Barbados’s Sugar Industry Takes Off

Up until the 1640s, life in Barbados was largely a bleak affair. Tobacco and cotton were the island’s principal crops, though neither grew in abundance compared to other nearby regions. The colony held little relevance in the eyes of the European powers right up until the first wave of Jewish migrants arrived from Recife. Armed with the knowledge of sugar cane rearing, a skill picked up from generations of living in Brazil, the crop exploded onto the global scene.

“Together with the Dutch, the Sephardic Jews transferred the center of the New World sugar industry from northern Brazil to the Caribbean islands,” writes Richard B. Sheridan in his book, “Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623-1775.” “They brought knowledge of cane culture and processing, together with cane cuttings, seasoned slaves, mills, utensils, Holland and English wares, and African slaves. More than the Dutch, they were masters of sugar technology and taught the English the art of sugar making.” This sudden abundance of sugar cane led to an abundance of molasses — a byproduct that’s a key ingredient in the production of most rums.

Within 20 years of the mass migration from Recife, by the early 1660s, Barbados had become fabulously wealthy, spurring a greater quantity of trade than all other English colonies put together. Though the Sephardim kick-started this rampant economic growth, they had little to show for it. “From the outset, Barbados’s Jewish inhabitants settled in the colony’s towns, choosing to concentrate on commerce rather than on plantation agriculture,” writes Eli Faber in his book, “Jews, Slaves, and The Slave Trade: Setting The Record Straight.” “While some of Barbados’s Jews did own land outside the towns, concentration in the latter, hence in commerce, meant that the Jewish population was destined to own few of the island’s slaves.” While the Jewish community traded goods, rum being one of them, it was largely unable to reap the financial benefits of the sugar industry.

Barbados in the Modern Era

All good things must come to an end, and that included Barbados’s incredibly lucrative sugar trade. As surrounding islands and shores across the Caribbean began to cultivate their own cane, Barbados slowly fell to the wayside, unable to match the supply of its neighbors. Thankfully, the country had developed a deep affinity for rum over the centuries, spurring a consistent demand for the spirit even without a major surplus of molasses.

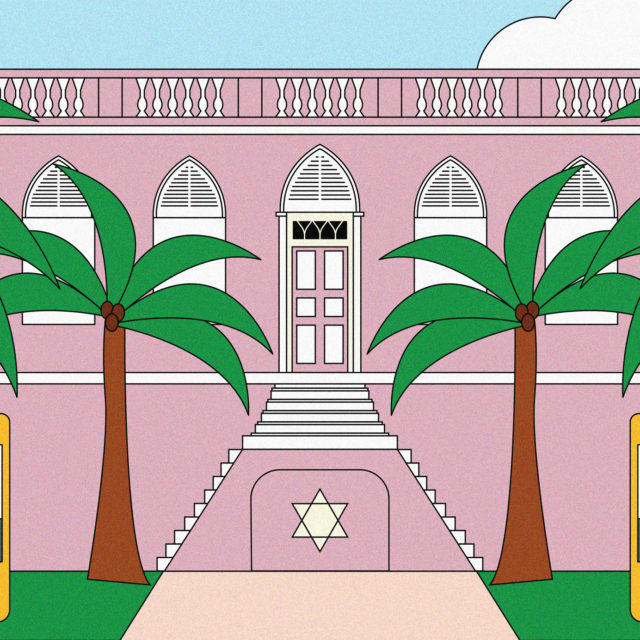

As with sugar production, the Jewish population began to dwindle as well. Today, Barbados is home to a small community of Jews, many of whom attend Nidhe Israel Synagogue, one of the oldest Jewish temples in the Western Hemisphere. Though they are small in number, there’s no denying the pivotal role that their ancestors played in the history of Barbados, as well as the rum industry as a whole. From the shores of the Caribbean to the isles of the Philippines, rum has established itself as one of the most favored spirits in the world — and we owe its success, in part, to a small sect of religious refugees fleeing persecution to begin life anew in a foreign land.