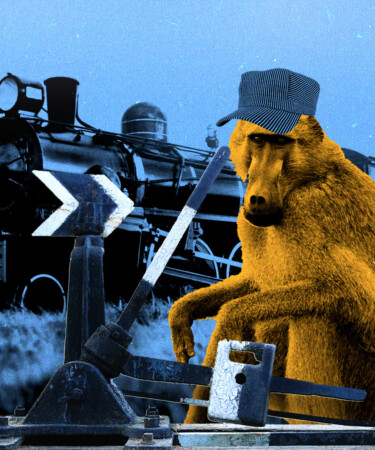

If you’ve ever seen the 1960s “Planet of the Apes” film — or any of the dozens of subsequent movies for that matter — you know how unnerving it can be to bear witness to primates behaving in a distinctly human fashion. Lucky for us, those films are entirely fiction. However, in South Africa in the late 1800s, a similar reality unfolded thanks to the Cape Town-Port Elizabeth Mainline Railways’ hiring of Jack the Baboon.

For nine years, the primate operated the railway’s switchboard, changing the tracks for incoming trains at the Uitenhage station, receiving 20 cents per day as payment in addition to half a bottle of beer per week. Perhaps most astonishing, in Jack’s near decade of work, he never made a single mistake.

Prior to Jack’s employment, the station’s switchboard was operated by James Wide, who was fondly nicknamed “Jumper” by his friends and colleagues thanks to his love of hopping from train line to train line, and car to car. In 1877, Jumper’s leaping resulted in a horrific accident. Rather than landing safely on the other side of the tracks during a jump, Wide slipped and fell beneath a moving train, remarkably retaining his life, but losing both of his legs in the aftermath.

Despite the fact that Jumper was miraculously still alive, learning how to live as a paraplegic was an incredibly difficult task. Though he had fashioned a set of peg legs to replace his missing limbs, his half-mile commute from his cottage to the train station was taxing, and his ability to do household chores diminished. One day, while walking around Cape Town, he came across Jack pushing an oxcart and purchased the baboon, immediately training the monkey to push his wheelchair.

Jack also took to helping Jumper out around the house they shared together, picking up household chores like taking out the trash and even sweeping the floors. Observing Jack’s quick nature and willingness to learn, Wide began training his companion to operate the signal box.

By watching his owner, Jack quickly picked up on the timing of the train’s alerting whistles as they approached the station and learned exactly which levers needed to be pulled to ensure the trains ended up on the proper tracks. For years, Jack worked with such efficiency and precision that no passengers would have had any idea it wasn’t a fellow human in charge of their fate. That was all until one day when a passenger allegedly looked out the window of their train car, noticing with what was likely extreme shock that it was in fact a monkey, not a man, sitting at the control board.

The story goes that both Jumper and Jack were promptly fired for this indiscretion, as Jumper made no attempt to conceal Jack’s work, proud of his pet and assistant. However, faced with few job prospects and the potential of losing his cottage — which was provided by the railway — Jumper returned to ask that Jack be put through a test to prove his ability to work competently.

Secret instructions were provided to each train operator passing through the station for the test so Jumper would have no opportunity to coach the baboon. Each train would toot its horn a set number of times, and the crew in the station watched on in amazement as he responded by pulling the correct levers each and every time in addition to double checking to ensure his trains were on the correct track. Shortly thereafter, both Jack and his master were invited to return to work, at which point Jack was granted an official employment number and his payment structure of 20 cents per day plus one half-bottle of beer per week.

Sometime in the late 1880s, railway superintendent George B. Howe declared that “Jack knows the signal whistle as well as I do, also every one of the levers.” Additionally, he reflected on Jack’s relationship with Jumper, stating that “It was very touching to see his fondness for his master. As I drew near, they were both sitting on the trolley, the baboon’s arms round his master’s neck, the other stroking Wide’s face.”

Following nearly a decade of loyalty and service for the Cape Town-Port Elizabeth Mainline Railways, Jack the Baboon tragically passed away in 1890 from tuberculosis. To this day, he remains beloved, with his skull on display at the Albany Museum in Grahamstown, South Africa.