Earlier this week, I posed a question on Twitter: What is the biggest threat facing the wine industry right now? Dozens of wine professionals weighed in. Macro challenges like climate change and the global recession led the charge. These were accompanied by a swift current of frustration surrounding the wine industry’s indifference toward consumers and its slowness to modernize (DTC, packaging formats, etc.). Peppered throughout were comments about the rise of wellness marketing and the “clean-washing” of consumers.

While the macro challenges are no doubt troubling, it’s these latter issues that have me most concerned about the future of wine. Industry analyst, consultant, and commentator Robert Joseph, of Meininger’s Wine Business International, said it best:

Apathy.

On the part of producers who believe (and are encouraged to believe by some media) they have a right to exist w/o changing. And on the part of consumers, most of whom don't really care very much what they're drinking, who made it, how and where.— wine thinker (@robertjoseph) August 4, 2020

That comment gets at the heart of my concern. Wine companies seem unwilling or uninterested in engaging with consumers on their terms, with messages they’re interested in hearing. And consumers — especially millennials — seem disinterested in the marketing messages that resonated with boomers and Gen Xers. So wine finds itself at an impasse.

Meanwhile, we have entered into an unprecedented period of innovation in the drinks industry, with breakneck product evolution propelling hard seltzer and RTD cocktail growth. Among millennials, health and convenience are driving purchasing decisions, and wine is losing market share. SVB Bank’s Rob McMillan called this a key challenge in his 2020 State of the U.S. Wine Industry forecast, stating, “There are solutions, but hoping millennials will adopt boomer values as they age — and, as a result, move away from spirits and gravitate to wine — just isn’t a sensible business strategy.”

You might think this would be a wake-up call for wine companies, that they would lean into the problem, looking to engage millennials where they’re at (reading product labels and online), with the messages they want to hear (nutrition and product information). Yet that’s not what’s happening.

So let me say it plainly: Millennials want to know what’s in the products they buy. That means ingredient labeling, nutritional facts, and product claims. It’s not a fad, and it’s not going away. If anything, the demand for this type of transparency is going to become louder. Yet wine companies are stonewalling, refusing to come clean about how they make their wines.

The wine industry’s opaqueness about its practices has done two things: It has turned many consumers off wine to other categories, like RTDs, that provide adequate product labeling. It also created an information void that dubious marketers exploited, demonizing commercial wine to promote their “clean wine.” This type of marketing relies on customer misinformation about how wine is made to sell its products, and it is snowballing.

How Did We Get Here?

By this point, most CPG categories have responded to rising consumer demands for transparency. Food, beverage, makeup, and household cleaners are among those that have added ingredients and disclosures to their labels and packaging. In fact, a clear majority (81 percent) of consumers say transparency is “important” or “extremely important” to them when shopping online and in-store, according to a report released in March, based on a survey of 1,000 online shoppers, most of them millennials, by the Food Marketing Institute (FMI) and Chicago-based Label Insight.

Some in the wine industry may argue that wine is special, and should be held to a different standard. But that’s not how consumers see it. It’s no longer good enough to put a region and a grape on the label — consumers expect more. In the Food Marketing Institute’s survey, respondents said the most important areas for labeling transparency were ingredients, certifications, and in-depth information about the nutrition of products, followed by product claim and allergen information.

Yet wine brands have not made it easy for consumers to find any of this information. Millennials search for information primarily through web and mobile platforms, but winery websites provide little useful information. There are plenty of vineyard vistas, tasting descriptors, and critics scores to be found, but not much about how the wines are made or what goes into them.

While wine lagged, hard seltzer and other RTDs picked up the slack. It’s no surprise that hard seltzer is the fastest-growing segment of the beverage alcohol industry, and that it’s taking share from wine, according to Nielsen. RTDs are already an $8 billion industry in the U.S., with volume that grew by almost 50 percent in 2019, due largely to the popularity of hard seltzers (led by brands such as White Claw and Truly), according to IWSR data.

Take Truly. The brand makes it easy to find product facts on its website and on cans. A can of grapefruit-flavored Truly lists that it has 100 calories, 5 percent ABV, 1 gram sugar, 2 grams carbs, and is gluten-free. The ingredients are filtered carbonated water, alcohol, natural flavors, cane sugar, citric acid, and sodium citrate.

For most consumers, that’s good enough on the labeling-transparency front. They want to know how many calories are in it, the sugar content, and the carb counts. Others, like vegan wine drinkers, are interested in knowing whether the wines use animal products like isinglass, gelatin, or egg whites. The wine spritzer Ramona gets this, disclosing the information in an easy-to-understand way.

Enter “Clean Wine” Marketers

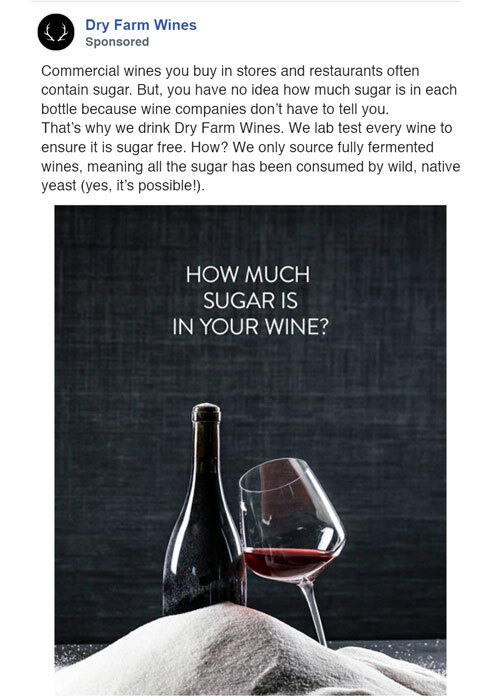

If natural wine opened the door, setting up a dichotomy between virtuous wines (organic, low-intervention) and dangerous wines (commercially made with pesticides and additives), “clean wine” drove a truck through it. Scout & Cellar, Dry Farm Wines, Good Clean Wine Co., and Winc’s Wonderful Wine Co., are among the many companies that have perfected the art of health-related, buzzword-heavy, word-salad marketing. (For a deep dive on the deceptive marketing tactics of “clean wine,” check out the VinePair Podcast episode “The Dirty Truth About Clean Wine.”) They all use the same techniques, preying on consumers’ lack of understanding about how wine is made, and pitting their “clean wines” against the “dirty wines” sold in restaurants and stores. Take a spin through Dry Farm Wine’s Facebook Ad Library for a master class on the topic.

According to this Dry Farm Wines ad: “Commercial wines you buy in stores and restaurants often contain sugar. But, you have no idea how much sugar is in each bottle because wine companies don’t have to tell you.” While wine professionals may scratch their heads, pointing out that most dry wines have little to no remaining sugar after fermentation, consumers are easily duped into thinking that “commercial wines” are loaded with sugar. (This ad is also ironic, considering that Dry Farm sources commercially available wines that — gasp — are sold in stores and restaurants.)

And ignore the fact that most dry wines would qualify as low-carb, low-sugar when Wonderful Wine Co. can rebrand that information as “paleo-friendly.” “On top of being low sugar and low carb, our wines are crafted using minimal intervention winemaking practices. It’s basically what a caveman would do — if that caveman had a degree in viticulture,” according to its website.

Frankly, I think that Cameron Diaz’s Avaline — a brand that has been under attack since it launched last month for its “clean wine” marketing messages — is among the least problematic in this segment. The brand is giving consumers what they want: transparency (or at least the illusion of it). On its website, Avaline lists the ingredients and processing aids that went into its wines, with simple explanations about why they were used: sulfites, bentonite, pea protein, cream of tartar, yeast, and yeast nutrients are all there. The wine label clearly states its health claims: “Made with organic grapes. Free from added sugar, artificial colors, concentrates.”

Yes, I get it that Avaline says its wines are “transparently produced,” and that statement sounds false to most in the wine community. But that’s because wine professionals define transparency differently than consumers. Transparency, to those in the industry, means a tech sheet filled with complicated information that would make a casual imbiber’s eyes glaze over. I know it may be hard to accept, but most consumers, as Joseph stated it, “don’t really care very much what they’re drinking, who made it, how and where.”

For wine companies, that means reconsidering brand marketing techniques. Pastoral landscapes and winemaker stories are not as persuasive to millennials as cold hard facts. Brands can take a page from Avaline by stating, in simple terms, what is in their wine, and explaining the ingredients and processing aids that were used. Permitted chemicals and additives (deemed safe by the TTB, by the way) like grape concentrate, yeast nutrients, tartaric acid, calcium carbonate, oak chips, isinglass, and others sound less scary when they’re explained.

This is a relatively simple concept, yet few wine companies are willing to do it. I commissioned an article in 2017 on labeling transparency. At the time, Wine Institute, a public policy organization representing more than 1,000 wineries and related businesses in California, said the issue was not a priority for the industry or for consumers.

I followed up this week to ask if that had changed. “We recognize that there is a growing interest among some for ingredient labeling and are exploring how this could work for wine,” spokesperson Nancy Light told me. “Wineries are permitted to voluntarily list ingredients but there are no standards about what must be listed.”

Yet, movement on this front has been glacially slow. In 2017, I could only find two wineries disclosing ingredients and processing information: Ridge Vineyards and Atlas Wine Co. Since then, I’ve added Long Island’s Shinn Estate Vineyards to the list, but these companies are far and away the outliers. They were ahead of their time, anticipating the “clean wine” reckoning that has indeed materialized. Their wine labels and websites are a template for the kind of fact-based, accurate labeling and disclosure information that is useful to consumers, providing a level of transparency that isn’t peppered with the nonsense claims of “clean wine.”

Had other wine companies followed suit, providing easy access to ingredients and nutritional facts along the way, helping to educate consumers about how wine is made, the industry wouldn’t be facing its current situation. Now, “clean wine” marketers have positioned the entirety of commercial winemaking as dangerous and suspect. My hope is that the wine industry takes this threat seriously, labeling its wines and disclosing its processes, before millennials turn off the category for good.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!