The sun was setting behind a group of wine professionals at a party on a Brooklyn rooftop when their conversation suddenly became animated. They had started comparing terroir, the somewhat intangible connection between wine and the place it was grown, to regional hip hop scenes. You can tell if an emcee is from Queens or Virginia Beach or Inglewood just by listening, they said, and the same idea applies to wine. Every song and bottle reflect their environments in physical and abstract ways.

It was the sort of discussion you could participate in even if you hadn’t worked a harvest in Burgundy or memorized a WSET textbook. And it’s the kind Jermaine Stone is eager to facilitate.

“Wine culture can get so academic that people feel like, in order to enjoy it, you have to enjoy academia,” Stone says in a phone call with VinePair. He was at the heart of that rooftop exchange, and finds he’s better able to bridge his two passions, wine and hip hop, by “bringing a human voice to it.”

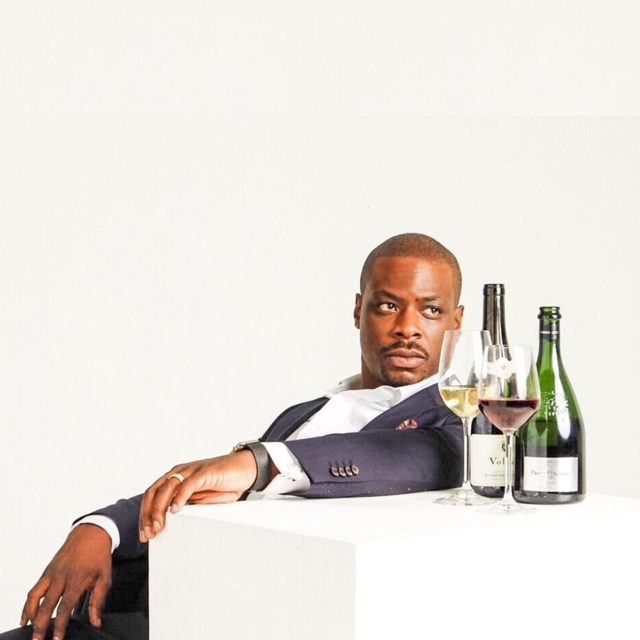

Stone, 34, is the president and CEO of Cru Luv Selections, a branding and marketing company “dedicated to blending all the best elements of wine and hip hop,” he says. Cru Luv hosts charity auctions and live events in conjunction with Stone’s podcast, “Wine & Hip Hop,” and consults with a variety of wine companies. Before all that, Stone, who is originally from the Bronx, was a rapper.

“Hip hop is the No.1-consumed form of music in the world,” Stone says. “Honestly, I feel like there will be a tidal wave in the next year or so with a bunch of hip hop wine products.”

In 2015, Spotify analyzed 20 billion tracks and found hip hop is the most listened-to genre worldwide, regardless of geography and language. According to Nielsen data, hip hop/R&B outpaced rock to become the most consumed musical genre in the United States in 2017. Of the 19 songs streamed more than 500 million times in 2017, 17 were by hip hop artists, USA Today reports.

“It has grabbed global attention and sparked emulation in countless different countries and among varied ethnicities,” the academic Michael Eric Dyson writes in his book, “Know What I Mean? Reflections on Hip Hop.”

Given the cultural and economic breadth and success of hip hop, it makes sense for brands to market products to the community. The sneaker company Puma, for example, asked longtime collaborator Jay-Z to serve as creative director when it launched its first basketball shoe in 20 years in September 2018. “Now, Jay-Z, who understands hip-hop and entertainment in the US, helps Puma basketball make decisions on everything from the tone of voice it uses, to how it works with athletes, to the events it holds,” writes Quartz’s Marc Bain.

The decision paid off. According to Puma CEO Bjørn Gulden, the company had its best quarter ever in early 2019, with sales in the Americas up nearly 20 percent.

In the wine industry, understanding the economic and cultural potential of hip hop has been a long time coming.

“Since 1996, Jay-Z has been making smart metaphors, smart correlations between wine tasting and cool street life,” Stone says, calling Jay-Z “the No. 1 hip hop wine connoisseur in the world.” His 1996 song, “Can’t Knock the Hustle,” includes the line, “I sip fine wines and spit vintage flows.” Jay-Z also mentions Petrus in the 2005 track, “Whatchu Want,” and Ace of Spades in 2006’s “Show Me What You Got.” Ace of Spades is a nickname for Armand de Brignac, the Champagne Jay-Z would go on to purchase in 2014.

In 2006, Jay-Z initiated a boycott of Cristal following remarks Frédéric Rouzaud, then-president of Cristal’s parent company, Champagne Louis Roederer, made in an interview with The Economist. “We can’t forbid people from buying it,” Rouzaud said of Cristal’s popularity in rap music and culture.

“Surely he meant to say, ‘Thank you,’ right?” Jay-Z commented in The New York Times at the time. “Anything but a ‘Thank you’ is racist.”

Jay-Z isn’t the only rapper referencing wine in their lyrics. Others include Nas (“I sip the Dom P. watching Gandhi til I’m changed,” “The World is Yours,” 1994); Notorious B.I.G. (“Back of the club sippin’ Moet is where you’ll find me,” “Big Poppa,” 1994); Lil Kim (“Still over in Brazil sipping Moscato,” “Lighters Up,” 2005); Kendrick Lamar (“When things get hard to swallow we need a bottle of Moscato,” “Moscato,” 2011); Fabolous (“Let’s just finish up this Riesling,” “Riesling and Rolling Papers,” 2011); and many others.

These mentions prove that hip hop artists and audiences are, for their part, engaging in wine culture. Why, then, aren’t more beverage companies making the connection?

“A lot of the people controlling these larger wine companies just simply don’t know hip hop culture enough to realize the actual market’s potential,” Stone says. “If these companies were paying attention they would see that the interest is there.”

The hip hop community has demonstrable wine buying power, too. In 2013, NPR’s Sam Sanders linked the “astronomical” Moscato sales growth to its prevalence in hip hop lyrics, citing songs by Waka Flocka Flame, Lil Kim, and Drake. From 2010 to 2011, Moscato sales generated $300 million, up more than 70 percent, according to Nielsen data.

A savvy marketer could view the success of Moscato as a harbinger of sales to come. They might analyze which wine varieties and labels are already popular among hip hop fans, and position related products accordingly. (“Let’s get a conversation going about Sauternes. Because guess what? A lot of people would love it,” Stone says.)

Stone recalls working in wine auctions in Hong Kong in 2008. “When they lifted the import tax on wine, every single company was marketing blue-chip Bordeaux to Asia — and they were doing it successfully,” he says. “There were a bunch of other expensive wines that weren’t doing as well, like big California Cabs, because that market hadn’t been developed yet. They were only familiar with the name-brand wines.” Throughout the last decade, as tastes have evolved in Hong Kong and mainland China, so have imports.

In marketing, and life, anyone new to a culture has to identify the line between enthusiastic adoption and pandering or profiteering. “So often, you have the black story being told by people who didn’t live it, and that tends to dilute it a lot,” Stone says.

“The first rap hit was Sugarhill Gang’s ‘Rapper’s Delight’ … but that’s not what rap really sounded like in the creation.” Other rappers, like Bronx innovator Grandmaster Caz, were culturally more relevant, but a New Jersey record label executive reportedly decided Sugarhill Gang’s disco remix would be easier to market to mainstream radio in 1980.

These days, new platforms bring music directly from artists to listeners, eliminating the need for radio approval. Similarly, American wine culture is shifting. Sommeliers, not critics, are the new tastemakers, Stone says, and people like Dustin Wilson and Andre Mack are creating more accessible and inclusive wine communities than the Robert Parkers of yesteryear.

Restaurants are evolving in tandem. “I go into restaurants and all I hear is old-school hip hop — real hip hop, with the curses,” Stone says, laughing. “That comes from our generation being raised on hip hop. People that are going out to restaurants are saying, ‘I’d like to hear Method Man with my entree.’” Imagine the wine pairing possibilities.