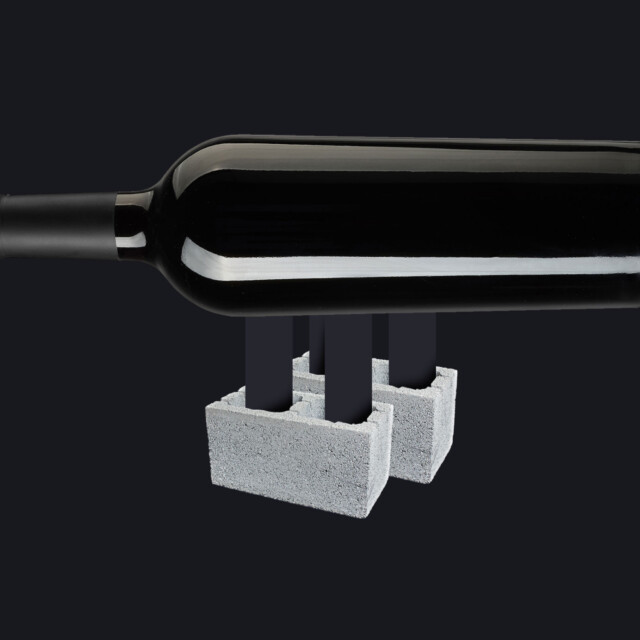

Spend enough time enjoying, collecting, or working with wine, and you’ve come across them. At first glance, they make perfect sense. They’re an impact statement; an impressively cocksure declaration in brawny, glossy glass.

The message? “I’m important. I’m serious. I’m powerful. You should pay more for me.”

Thick, heavy glass bottles certainly had their moment in the sun. In the ’90s and aughts, these Patrick Batemans of the packaging game literally threw their weight around to great effect — carving up the image of reasonable, normal glass wine bottles and accumulating prestige market share. Hedge fund collectors and the nouveau riche fawned over the transparently self-aggrandizing, liquid-centered cinder blocks of the trade. “Regular sized 750-milliliter bottles? That’s for losers,” they declared. “All hail the 750-milliliter heavies!”

But recently, if slowly, the wine world seems to have finally caught on to the magnificent absurdity of it all. And while there has been a gradual shift in attitude — and even some economically charged activism by some wine producers — there hasn’t yet been a universally revered figure within the hallowed inner sanctum of the old-school wine-reviewing elite who has unequivocally proclaimed: “No more! I’m out. I’m done.”

That is, until one of America’s most celebrated wine critics and authors finally slammed the door on overweight bottles — emphatically and permanently.

Prominent Reviewer Goes Scorched Earth on Heavy Bottles

On Jan. 15, Karen MacNeil — influential reviewer, writer, and author of touchstone opus “The Wine Bible” — announced that she and her popular digital newsletter WineSpeed would no longer write about wines packaged in heavy, thick glass.

There have been growing grumblings in the wine industry that this type of grandiose packaging was distinctly problematic — with the estimates of a bottle’s contribution to wine’s overall carbon footprint varying between 30 and 68 percent. And in fairness, several among the wine-literature intelligentsia have been calling out these tone-deaf, cringe-inducing bricks for years.

The highly esteemed U.K. wine journalist and co-author of “The World Atlas of Wine,” Jancis Robinson, has justifiably railed against what she terms “bodybuilder bottles” for almost two decades. She points out that bottle weights are now included in all her reviews — slinging shame at the overt heavies and praising those who virtuously embrace a more delicate packaging aesthetic. As a pioneer in the heavy-bottle haters club, Robinson has lent her undeniably influential voice to an ever-increasing coalition pushing progressively more forcefully for lighter, more ecologically friendly practices.

And yet, no one among the top echelon of wine writers had dared to completely throw down the gauntlet with an unyielding, binary, in-or-out stand.

“There are a lot of obscene bottles. The industry as a whole should start moving away from it, [but] the perception that weight is attached to quality, it’s still definitely a thing.”

MacNeil’s proclamation was met primarily with cheers and praise — as well as a predictably accusatory, light strafing regarding so-called “virtue signaling” from certain corners. As for her thought process to go ahead and cross the Rubicon? It seems to have been an opportune fusion of frustration meets platform.

“We do a lot of tastings. And yet again, the day before the announcement, there was this heavy bottle,” MacNeil says, referring to an obnoxiously overweight submission that had just arrived for review. “These bottles are both frustrating and really just wrong in a way. I believe that each of us has a responsibility to do something, and I thought, ‘This is something that I can do.’”

The contrarian argument against such an insistently bold move suggests that, essentially, she’s overstepping her station in the wine business ecosystem by banishing an entire tract of the marketing and packaging landscape.

But when asked, MacNeil is clear-eyed about her decision; undaunted by the criticism. “I think sometimes journalists may feel it’s not their role to suggest what a winery should or shouldn’t do,” she says. “But I only said what I’m doing. I’m not reviewing or writing about them anymore. And if certain wineries write me off, then so be it.”

Wineries, Retailers, and the Aching Backs of Their Employees

Reviewers and writers are far from the only layer in the wine business lasagna to start taking a principled stand — or at least strongly suggesting a change in wine-packaging strategy. Retail heavyweights, like Ryan Woodhouse at K&L Wine Merchants, are also having their say in the matter.

As the domestic buyer at California’s oft-referenced retail institution, he is frequently saddled with the worst of it. “There are a lot of obscene bottles,” Woodhouse says. “The industry as a whole should start moving away from it.” However, he’s quick to temper his stance with an admission that old habits die hard, and change can be slow. “The perception that weight is attached to quality, it’s still definitely a thing,” he adds.

The fact is that, for the moment, the majority of “prestige’” bottles from glitzy regions like Napa — and therefore producers most likely to employ beefy glass to emphasize a presumed “glamor factor” – are purchased by an established and older wine-drinking demographic which is comfortably accustomed to the “heavier-is-better” fallacy. And from Woodhouse’s informed perspective, barring some kind of regulatory intervention, it could be a bit of a process to divorce bottle weight from perceived quality among this particularly fixated flock. “It may be far slower adoption than we hope,” Woodhouse says. “It needs to be a systemic and generational shift.”

“When we realized that 80 percent of our customers were in favor [of lighter bottles], it was an easy decision to make.”

Curiously, though — from the winery perspective — shaving down bottle weights is likely cash in the bank. Any lost sales are almost certainly compensated by a massive cost of goods reduction.

“I had no idea we’d save that much money!” says Jason Hass, proprietor at Paso Robles standard-bearer Tablas Creek Vineyard. “It makes good economic sense.” By doing the right thing environmentally, the lauded producer ended up banking a cool $2.2 million in savings over the first 14 years of its lighter-glass expedition.

“Consumers are much more willing to experiment with different packaging than we give them credit for,” he adds. The generations are progressing on down the line, and those still clinging to the ego-bloated five-pound bottle trend are slowly but surely decreasing in economic importance. Tellingly, wineries ranging from supermarket standout Bogle, to boutique Napa upstart NeoTempo, are now rolling out innovative alternative 750-milliliter bottles utilizing lightweight aluminum and geometrically advantageous glass, respectively — contributing a pincer maneuver of alt-packaging legitimacy from opposing ends of the price and aesthetic spectrum.

And lastly, lest we forget, there are the weary lower backs of the average beverage industry employee to consider. The indispensable worker bees of the trade are often burdened with the unenviable task of hauling full cases filled with these malevolent masses one after the other — sometimes for hours on end. A pallet drop of 55-pound boxes frequently means a night spent on the heating pad. It’s a thankless task, and one that can often feel like a personal insult.

“I’m surprised that OSHA [Occupational Safety and Health Administration] hasn’t looked into this yet,” quips MacNeil — only half joking.

Industry-Wide Change for Wine Packaging?

In the end it’s likely good old-fashioned capitalism — and the inherent marketing benefits of ecologically responsible bottles — that may finally shatter the will of fat-bottled holdouts. Sure, that may be a mildly callous way to look at it. But if it gets the job done, well, why not?

Wine sales are losing ground at an alarming clip both in the U.S. and globally. The culprit is a generational sea change in drinking preferences and viable marketing strategy.

For a wine industry seemingly befuddled with how to entice younger drinkers away from beer, spirits, and RTD beverages, it’s a silver-trayed, white-gloved helping of easy win. “This is a really important way to make sure that we are listening to the concerns of younger wine drinkers,” Haas says. “When we realized that 80 percent of our customers were in favor [of lighter bottles], it was an easy decision to make.”

Finally, at its core, it’s self-evident that wine is an industry that is innately and inextricably intertwined with the state of the environment. So, why isn’t there more of a push like this for wineries to have their cake and eat it, too?

Sustainability is supposedly consumer catnip to the younger generations. Smart producers are already starting to pluck that ripe, low-hanging fruit. MacNeil agrees with the idea. “Millennials and Gen Z: What’s important to them for wine? Sustainability and environmental conscientiousness,” she says. It’s a no-brainer. A win-win. A generational marketing dragon all but slayed.

On a curious note, of many inquiries sent to several other major reviewers to discuss heavy glass and MacNeil’s announcement, most were either ignored or deflected. It’s anyone’s guess whether or not this suggests an underlying hesitation to wade into the subject — and potentially feel called-out by comparison, though that certainly wasn’t the spirit or intention of the inquiries. On the other hand, I’ll admit it’s equally plausible they simply didn’t have the time to discuss the matter. Reviewers are necessarily very busy people. I get it.

Regardless, from this wine writer’s humble perspective, I’ll wager that we’ll be hearing more from other reviewers on this subject — and its myriad adjacent concerns — quite soon.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!