In the mid-1970s the United States faced a recession, spawned by the 1973 oil crisis and stock market crash and skyrocketing unemployment rates. Suddenly, most Americans had less money to spend on consumer goods. But for a capitalistic society to function, people need to keep buying things, so companies had to figure out new ways of selling them.

Starting in 1977, no frills, generic brands began landing on shelves at supermarket chains like the Chicago-based Jewel, Iowa’s Aldi-Benner, and Canada’s Dominion and Loblaw, which literally offered a “No Name” line of goods. These were mostly the same items as before, but without the added costs of glossy packaging, variety, and advertising.

“‘No frills’ groceries are unbranded versions of commonly bought products,” wrote The New York Times, explaining the concept. The article cited such generic items popping up as paper towels, throwaway plastic utensils, mayonnaise, and canned vegetables “sold by most supermarket chains without advertising, in plain white packages with simple black lettering.” They cost anywhere from 30–50 percent less than branded items.

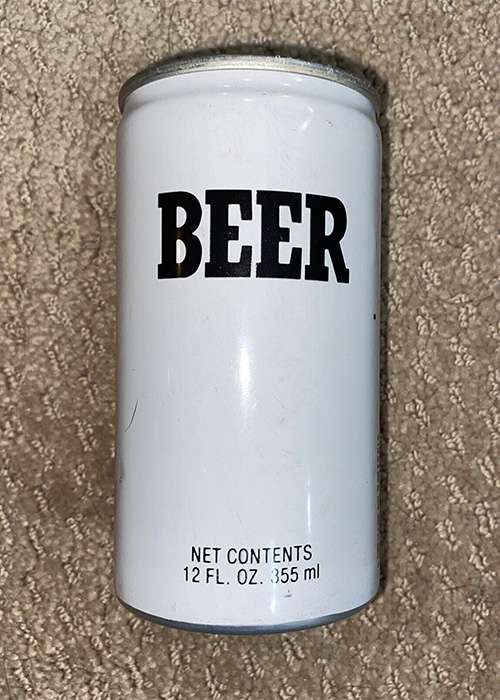

By 1979 there also arrived on shelves a 12-ounce can, completely white with no artwork and no information other than product weight, a UPC code, and, in big bold letters, one simple word: “BEER”

Profit Uber Alles

Many breweries were struggling in the 1970s and consolidation swept the industry with big brands acquiring smaller brands in droves.

“[His] big plan was to eliminate all marketing, fire hundreds of longtime employees, and slash expenses to the bare bone. Kalmanovitz went through Falstaff like Grant through Richmond. He took no prisoners.”

In the 1960s, St. Louis’s Falstaff Brewing was the third-largest brewery operation in America (behind only Anheuser-Busch and Jos. Schlitz Brewing Company), with seven plants nationwide. But by the mid-1970s, Falstaff, too, was cash-strapped, losing $3.5 million a year and embroiled in an antitrust case in the Supreme Court. In April 1975, Paul Kalmanovitz, owner of General Brewing Company, acquired Falstaff, which had slipped to sixth-largest brewery in the nation. In doing so, Falstaff joined a portfolio that already included Pabst, Stroh’s, and Olympia.

By many accounts, Kalmanovitz was a real piece of work — a curmudgeon who banned telephones at his company, refused to donate any of his inestimable wealth to charity (“[N]obody tells Kalmanovitz who gets the money. I decide,” he was reported as saying), and who for years tried to get a rival to the Statue of Liberty, called the Statue of Justice, installed in San Francisco Bay.

He was a man obsessed with “profit uber alles” (profit above all else), according to a judge who fined him $1.3 million in 1979 for breaching a contract. And Kalmanovitz continued to add to his coffers by specializing in leveraged buyouts, which he did with Falstaff.

“[His] big plan was to eliminate all marketing, fire hundreds of longtime employees, and slash expenses to the bare bone,” wrote drinks writer Bryan Dent in 2017. He immediately shut down the Falstaff plant in St. Louis and fired 175 employees in the corporate offices, took away their pensions, and sent them severance checks that bounced. “Kalmanovitz went through Falstaff like Grant through Richmond,” his business associate Lutz Issleib told Forbes at the time. “He took no prisoners.”

One of the Falstaff breweries that remained open, however, was a Fort Wayne, Ind., location, which pumped out 1.2 million barrels of beer annually. Kalmanovitz may have fired most of his employees and ravaged a beloved brand, but he still had the ability to brew beer, and in beer — especially cheap beer — he saw money.

Looking at all the generic products now filling supermarket shelves, Kalmanovitz had a plan.

A Cheaper Quaff

The mid-1970s were a golden age for beer marketing and advertising. Though they hadn’t engineered the concept, Miller revolutionized beer branding by leaning heavily into Miller Lite, which launched in 1973. Backed by the deep pockets of then-owner Philip Morris, the company spent some $90 million on advertising the product that decade, notably via its iconic “Tastes Great! Less Filling!” TV spots featuring retired athletes like Bob Uecker and Bubba Smith, and comedian Rodney Dangerfield.

But Kalmanovitz and Falstaff’s “BEER” didn’t have any of that. First released in the summer of 1979 at supermarkets like Piggly Wiggly and Valu King, the product had no ads, no commercials, no celebrity spokesmen, no distribution costs, and certainly no trendy packaging.

What it did have going for it was price: It sold for $1.19 a 6-pack, or less than a quarter a can. (Standard beer at the time was around $2.50–$3 a 6-pack.)

“There is a move afoot to obtain a cheaper quaff. [P]eople are actually casting aside such venerable institutions as Miller time and the Hamm’s bear in favor of an unnamed, unadvertised, unimpressive, unassuming beer called Beer.”

“Apart from being a cheap beer, not much else is known about the formulation of the beer,” claims beer historian David Healey. Stylistically, it was a pale lager, but other than that, many believed it was leftover beer General Brewing had sitting around, whether Falstaff, Ballantine, Lucky Lager, or perhaps something even less noteworthy. Healey, who has examined a 1980s recipe book from the Ft. Wayne Brewery found no particular specs or even mention of BEER, though he did find one for a generic light beer, which may have been BEER Lite, released at the same time.

“Rumors abound that generic beer was just something of whatever extra brew was left over and was even a blend of leftover beers sometimes,” he says. Nonetheless, it was an immediate hit in a nation lacking purchasing power — so much so that there were reportedly waiting lists at stores vying to get BEER stock.

“There is a move afoot to obtain a cheaper quaff,” wrote Tony Brown of the Argus Leader in 1980. “[P]eople are actually casting aside such venerable institutions as Miller time and the Hamm’s bear in favor of an unnamed, unadvertised, unimpressive, unassuming beer called Beer.”

Even Falstaff execs didn’t exactly understand the fervor. “If you can find someone to explain it, let me know,” said Jean Piatt from their Omaha sales office. “It gets you drunk just like the other stuff,” an anonymous college student retorted.

Other breweries and supermarket chains quickly took note.

Du Bois Brewery out of Pittsburgh — today more well known for its Iron City beer — offered a black-on-white BEER brand, sold at Schnucks stores. Grocery chain Ralph’s was the first supermarket to get into the generic beer game via a line of Falstaff generics with names like President’s Choice and “Cost Cutter” BEER, complete with scissors on the label. Iowa’s Pickett & Son had a generic beer. So did Minnesota’s August Schell Brewery.

Pearl Brewery out of Texas had a BEER labeled with a very era-specific space-age font, and would also release a generic can with an entire MAGA-esque screed on it, in part reading:

“WAKE UP AMERICA! Be a good American and buy American” followed by another 100 words or so urging drinkers to contact their congressman.

Falstaff’s success, meanwhile, had so galvanized Kalmanovitz that he used the other breweries under his helm — ones in Omaha, Milwaukee, and Vancouver, Wash. — to produce their own generics. By then, BEER and BEER Lite accounted for about one-third of his breweries’ production.

Lost Interest

By 1980, the economy was so bad that President Carter announced anti-inflation legislation and Falstaff agreed to not raise prices on its already cheap beer. By the end of 1982, such tight monetary policies finally allowed the U.S. to get out of its worst downturn since the Depression. Generic items were still selling well, however, peaking in 1982 and 1983 when they accounted for 2.4 percent of all grocery sales.

From that point on, though, as the economy greatly improved, generic sales steadily declined. As Michael Rourke, a grocery store executive, told The New York Times in 1986, “The consumer has lost interest.”

Kalmanovitz died the next year — his associates celebrated the death of their boss with shots of Jack Daniel’s; he lay to rest in a $6.5 million mausoleum — but Falstaff continued to release BEER and BEER Lite, the latter of which faced a lawsuit from Miller over the term “lite.” Falstaff ended up prevailing, with the court ruling that term could not be appropriated by one brewer.

General Brewing continued to close and sell its remaining breweries over the following years. Finally, in 1994, when its Fort Wayne brewery was shuttered for good, the last generic beers in existence were unceremoniously taken off shelves. The craft beer revolution was heating up by this point and drinkers wanted Pete’s Wicked Ale and Magic Hat No. 9 and Sam Adams Boston Lager.

They no longer wanted BEER.