It’s a chilly, drizzly November evening but on Platform 1 at London’s Victoria Station, spirits are high. No wonder: Ahead lies a four-hour ride around Kent on the swanky British Pullman train, taking in a five-course dinner prepared by Irish chef Anna Haugh, entertainment (including singing troupe The Spitfire Sisters), lavishly decorated historic railroad cars — and, perhaps most importantly of all, a bottle of Dom Perignon’s 2012 Vintage Champagne for every couple.

A fairly unique and, at more than $650 a ticket, expensive experience, the Belmond’s British Pullman service is typical in one aspect: It demonstrates the European passion for drinking on the move. From German Wegbier, open-container beer drunk on Berlin streets and en route to Bavarian biergarten, to cross-continent rail journeys, Europeans love to combine the necessity of travel with the pleasure of a good glass.

Now more than ever, that’s true. Beer sales onboard Deutsches Bahn trains doubled during the first six days of July’s European soccer championships; rail companies across Europe are adding bespoke beers to their catering offering; and “beer bike” tours, though they can be controversial, are popping up in cities from Bristol to Bratislava. This is a phenomenon that’s clearly going places.

A Good Lauf

On Berlin’s Adalbertstrasse, the Wegbier of choice appears to be Sternburg Export; in the streets around Munich’s central station Augustiner Hell dominates, with Tegernseer a distant second; and on Hamburg’s ever-seedy Reeperbahm, Astra is most popular with locals.

The brands vary but the tradition remains. In some European countries and cities, drinking in public is banned, such as Glasgow in Scotland, where open containers have been verboten since the late 1990s. But it’s a vital part of the culture in Germany, where 84 percent of beer is consumed packaged rather than on draft.

“There used to be a room full of beer to drink on the way home. There’s not much better than a walk with a beer on a sunny day.”

It’s something Germans learn at an early age. “Father’s Day in Bavaria is a bit different,” laughs Helen Busch, beer sommelier for the German Kraft brewpubs and bars in Vienna and London. “When I was younger, my father and his friends would fill up a pull-trolley with beer and ice [on that day], drinking it on the way to a brewery.”

Busch grew up in Erlangen in Franconia, the northern third of Bavaria, widely regarded as Germany’s brewing heartland. One of her first Wegbier experiences came at the age of 16, as part of another key drinking-on-the move tradition: Kastenlauf, or crate run. On the opening day of Erlangen’s Volksfest, Bergkirchweih, young adults traditionally carry a 20-bottle crate to the event, drinking as they go. A 40-minute walk can take up to five hours. “We didn’t actually go to the beer festival that day,” she says.

A beer while taking a stroll is even part of German workplace culture, according to Reece Hugill, British brewer and owner of Donzoko, who spent time working in a laboratory while studying in Munich. “There used to be a room full of beer to drink on the way home,” he says. “There’s not much better than a walk with a beer on a sunny day.”

Pedal Pints

The German passion for Wegbier doesn’t extend to all drinking on the go. Beer bikes — a human-propelled vehicle, seating up to 16 customers, who drink as they pedal — have been restricted in Germany for many years over concerns about rudeness and, most unforgivable in Deutschland, holding up traffic. Other countries have taken a similar approach, including the Netherlands, where the phenomenon first reared its head in the late 1990s.

Nonetheless, they are still popular, with Britain in particular currently a growing market — although even here concerns remain, perhaps because they’re associated with rowdy stag parties.

“Increasingly we find our passengers are most interested in wines from the vineyards we pass by on the train. It’s like normal life is suspended.”

Beer Travel UK operates beer bikes in Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Liverpool, London, and Newcastle. The Bristol scheme launched in February; it costs £370 (around $470) for an hour’s trip around the city center, and customers bring their own beer. Thanos Koufis, operations manager, told The Times he thought beer bikes’ bad reputation was “a bit unfair.” He said “it’s a way of bringing people together and socializing in a physical activity with friends.”

Train, No Strain

When Hugill was considering names for a Donzoko beer to be served on Lumo, a budget rail service between London and Scotland, one option stood out: Train Beer. In the U.K., “Train Beers” — carry-on beers bought in station stores — are hugely popular. “So why not call it Train Beer?” he says of the pale ale, which is served in 330-milliliter cans on the company’s eight daily services.

Britons enjoy taking their own beer (or RTDs, which are increasingly popular) on trains but, as Hugill points out, MittelEuropa is the place to go for a really classy experience. His passion for train beer was sparked by a journey between Venice and Vienna, when Austrian lager Stiegl was served on board in a glass. “I thought, ‘This is mint,’” he says. “It’s so much better than having to drive.”

(Beer served in a glass is common in this part of the world, from Germany to Czechia, where Pivovar Chroust brews exclusive beers for dining cars.)

Few people have as much experience of European train travel as Mark Smith, English creator of “The Man In Seat 61,” a comprehensive guide to rail travel around the world. Smith says a personal favorite is Erdinger Weissbier as served on German trains. “It’s always served in the proper tall glass,” he says.

Not all rail companies are so liberal, he adds. In Sweden, for example, you can drink alcohol but only if you buy and consume it in the dining car, while it’s banned entirely on Scotrail trains (but not those connecting to the rest of the U.K.) and the London Underground — although in the latter case, enforcement is not particularly stringent.

Smith says that while dining has gotten worse on European trains due to dining cars being removed, the quality of wine and beer has not suffered. “I think it’s as good as it’s ever been,” he says.

Fizzing Along

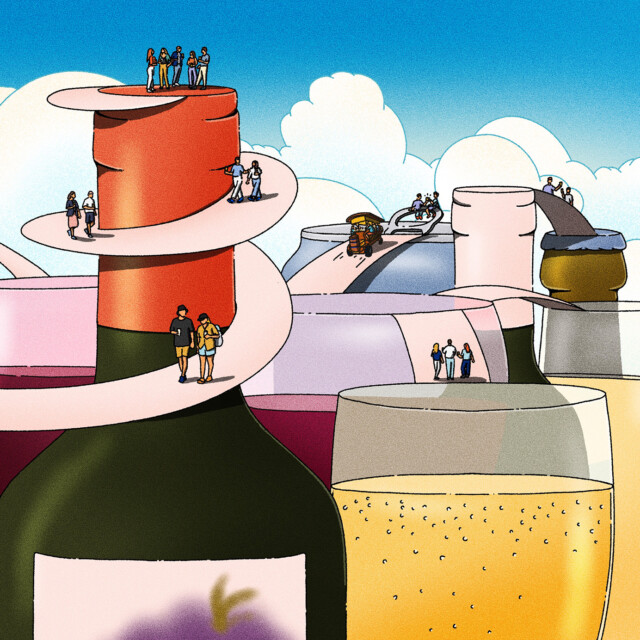

Sometimes, drinking on the go isn’t about getting anywhere, but the journey itself — as with the Belmond Pullman, where each passenger is greeted with a glass of sparkling wine as they arrive on board. The company runs a variety of journeys, from immersive murder mystery tours to afternoon tea, but perhaps the most intriguing are those that take in one of Kent’s growing number of vineyards, all within easy reach of London.

“Increasingly we find our passengers are most interested in wines from the vineyards we pass by on the train,” says Craig Moffat, general manager of British Pullman. There’s a special pleasure to enjoying a drink while you’re on the move, he says. “It’s like normal life is suspended.”

The same might be said of Wegbier — or even beer bikes, if the mood strikes you. It seems a particularly European approach to travel, a refusal to accept that even the most humdrum life moments shouldn’t be enjoyed. “You’re sitting there with your feet up, enjoying the countryside going past; why not have a glass of wine or a beer?” says Smith.

Why not indeed?