Beer, like our bodies, is mostly water. “Water is the most important ingredient in beer,” says Max Unverferth, one of the three brewers at the mobile beer outfit Nowhere in Particular.

In fact, it’s so important, the differences in the water in different locations will affect — sometimes deeply — the taste of the beer. And though it’s difficult to explain what exactly causes those differences in water, they will end up as differences in beer. “East Coast beers tend to be a little earthier, West Coast beers are danker, and Midwestern beers are juicier,” Unverferth says. “Much of that can also be traced to the ingredients and brewing methods as well, but you can’t overstate the importance of water in the overall taste of the beer.”

Sure, it might be sexier to talk wet versus dry-hopped, boil times, and the merits of Danko vs. Carolina heritage rye. But if you ignore H2O, the beer will be dead in the water.

Water is to beer as Kris Jenner is to the Kardashians. You know she’s there, behind the scenes, working her spooky, talon-nailed, spiky-haired jujitsu, and her powers can clearly be used for good – or evil. She must be obsessively watched and monitored, and frequently filtered to remove unpleasantness. Once filtered, she sometimes requires further manipulation. But under no circumstances can she be ignored, dismissed, or in any way downplayed. She will cut you.

Water is to beer as Kris Jenner is to the Kardashians. You know she’s there, behind the scenes… But under no circumstances can she be ignored.”

The typical beer is comprised of 90 to 95 percent water, so brewers worth their brewing salt spend a lot of time fretting and fussing over the stuff. This concern is of special importance for breweries like Nowhere in Particular (not to mention Evil Twin, Mikkeler, and the like) that travel from place to place, renting space here, collaborating there, all in the interest of making some good small-batch beer on a budget (and a mindset) that doesn’t allow for a permanent space.

Just this past year, they’ve brewed beers in Colorado, Detroit, and Ohio. San Francisco is next. “We do small batches in each place and it allows us to use different seasonal ingredients that are distinctive to each region,” Unverferth explains.

But the water is constantly an issue. “We would never even consider using water straight from the tap because it could introduce trace minerals or other elements that could react to our beers in an unexpected way,” he says. “We’re not in one place long enough to adjust for the regional quirks of its water.”

Apparently, simply sipping water and giving it the thumbs up or down doesn’t quite do the job, Unverferth, who studied chemistry in college, explains. “We break down the water and then build it up.”

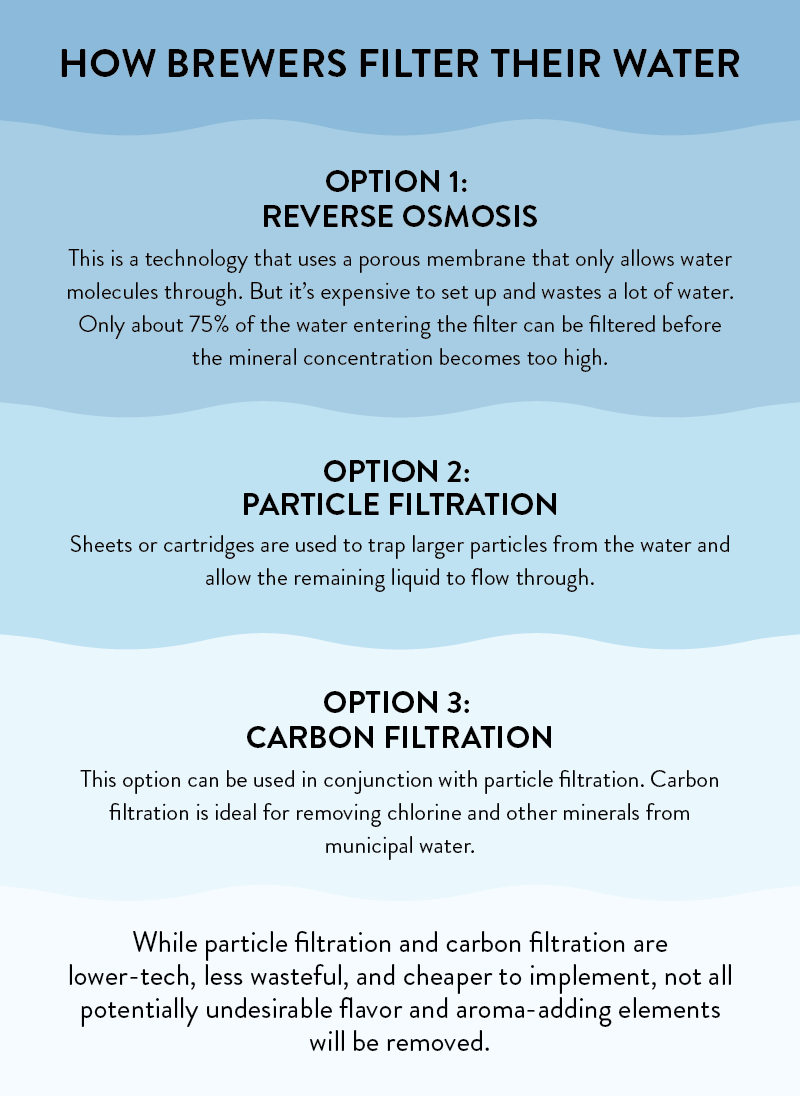

Nowhere in Particular uses reverse osmosis to purify its water, essentially removing ions, molecules, and larger particles from water. Through this high-pressure pump system, 95 to 99 percent of dissolved salts are removed. Once purified, Max and his cohorts – and most other serious breweries, small-batch or commercial — may add desired elements to the water before moving onto their recipe.

Water, and its filtration, is an integral part of brewing no matter which way you cut it, explains Richie Saunders, the head brewer of Shmaltz Brewing. For Saunders, it’s about filtering out the regional vicissitudes of the water in different places or, sometimes, adding it back in. “When we as brewers look at the traditional European water profiles, we are generally looking at mineral content, so we can mimic water to match profiles for beers and characteristics we are trying to duplicate in our beers produced in the U.S. of A,” Saunders says. Say you’re living in Dublin and want to make an IPA. You’re going to want to manipulate the water to make it ideal for the beer you’re brewing, rather than just relying on the water that Dublin has to offer. “Yeah, you are removing the ‘terroir’ element,” Saunders admits. “But when we filter water, we don’t think of taking away character — more as maximizing the outcome, because we are able to take the water down to a base and allow ourselves to build the water up to almost any mineral mix we are focusing on based on the flavor elements we are trying to develop.”

When approaching a specific beer style, hardness and alkalinity can be a factor. So can trace minerals. For example, pilsners, a signature beer of the Czech Republic, have been made historically with soft water, or water without a high concentration of ions. Alkaline water has higher concentrations of bicarbonates, which can have a surprising effect on grains during the boiling process. Acids are extracted from grains during the boil and the alkalinity of the water neutralizes them, which can depress flavors or tease out a wine-like characteristic in the final product. Water that contains high concentrations of calcium chloride tends to produce hoppier beers, because hops cling to calcium.

If itinerant brewers depend on purification methods to reverse engineer the perfect water, what do brewers in permanent spaces do? Shmaltz Brewing Co., which has straddled the temp-perm worlds of brewing by circumstance, not design, has a bird’s eye view of both ethos. The brewery was founded in 1996 by Jeremy Cowan on a semi-lark in San Francisco, when he made 100 cases of He’Brew beer and hand-delivered it throughout the Bay Area from the back of his grandmother’s Volvo. In 2003, Shmaltz moved into Mendocino Brewing Co.’s facility in Saratoga Springs, N.Y, and in 2013, the brewery opened up what it hopes is a permanent HQ in a 20,000-square-foot brewery in Clifton Park, N.Y.

The brews Shmaltz has created have always been relentlessly offbeat, with tongue-in-cheek names like She’Brew Double IPA, Hop Orgy, and Funky Jewbelation, but with serious beer geek chops. The brewery has won armloads of accolades, including multiple gold medals at the World Beer Championships.

But behind the freewheeling appearance is Saunders and his team of scientifically-minded brewers measuring, tinkering, perfecting. Saunders has earned a rep within the industry of being able to pull off methodical madness, and because of that, Saunders does a lot of contract brewing for other beer labels. And when they make beer for a crew that hails from the West Coast or overseas, chances are, subtle differences in water quality will evade filtration technology and seep through to the end product, unless additional precautions are taken.

“When brewers call on us to reproduce brands for them in our facility, there is an expectation that products made here will meet the same standards as those products produced at the home brewery or other contract production brewery,” Saunders says. But there are differences, and often those differences in flavor come down to water. “We can bring the same raw materials into our brewery as the contract utilizes at their home facility, but the quality of the water can be a game changer,” he explains. “There are often conversations regarding water quality and adjustments to water before we really get into talking about recipes from the perspective of what most people think of as brewing raw materials. Fortunately for us, it has been very easy to manipulate water constituents to provide exactly what we are looking for in water for a recipe.”

The brewing industry’s relationship with its life-giving elixir is as complex as a season-ending twist on Keeping up With the Kardashians. From the cultivation of the grains and hops grown for beer to the waste involved in filtering to the manufacturing of the bottle itself, one of the most recent studies available on the subject estimates that it takes about 300 liters of water to make one liter of beer. Another study, from WWF/SABMiller, found that it required anywhere from 60 to 180 liters of water to create one liter of beer. Either way, that’s a monster footprint.

And in times of climate change and drought – especially in beer-thirsty water-starved states like California – that is of particular concern to everyone. Responsible brewers do their best to conserve and cut corners where they can; Sierra Nevada cut its water usage by 25 percent in recent years, while others are digging wells and building wastewater treatment facilities. Others, like Bear Republic and Stone Brewing, are investing millions in “green” water-purification systems that allow them to recycle water.

Stone Brewing, in a bid to out-green even the most earnest California hippie, created actual toilet-to-can beer. The San Diego brewer unveiled five barrels of the aptly named Full Circle Pale Ale, made from recycled sewage water, in March. The mayor himself showed up to indulge in Stone’s first public sampling of the bidet beer, declaring it both “fantastic” and also “delicious.”

Even the current-events-averse mouth-breathers among us are aware of recent public water scandals. From lead in Flint, Michigan to toxic chemicals found in drinking water in 13 states, we all know that we don’t always know what’s lurking in our water.

But who knew that beer water, while it can be toilet water, can’t be from the tap?