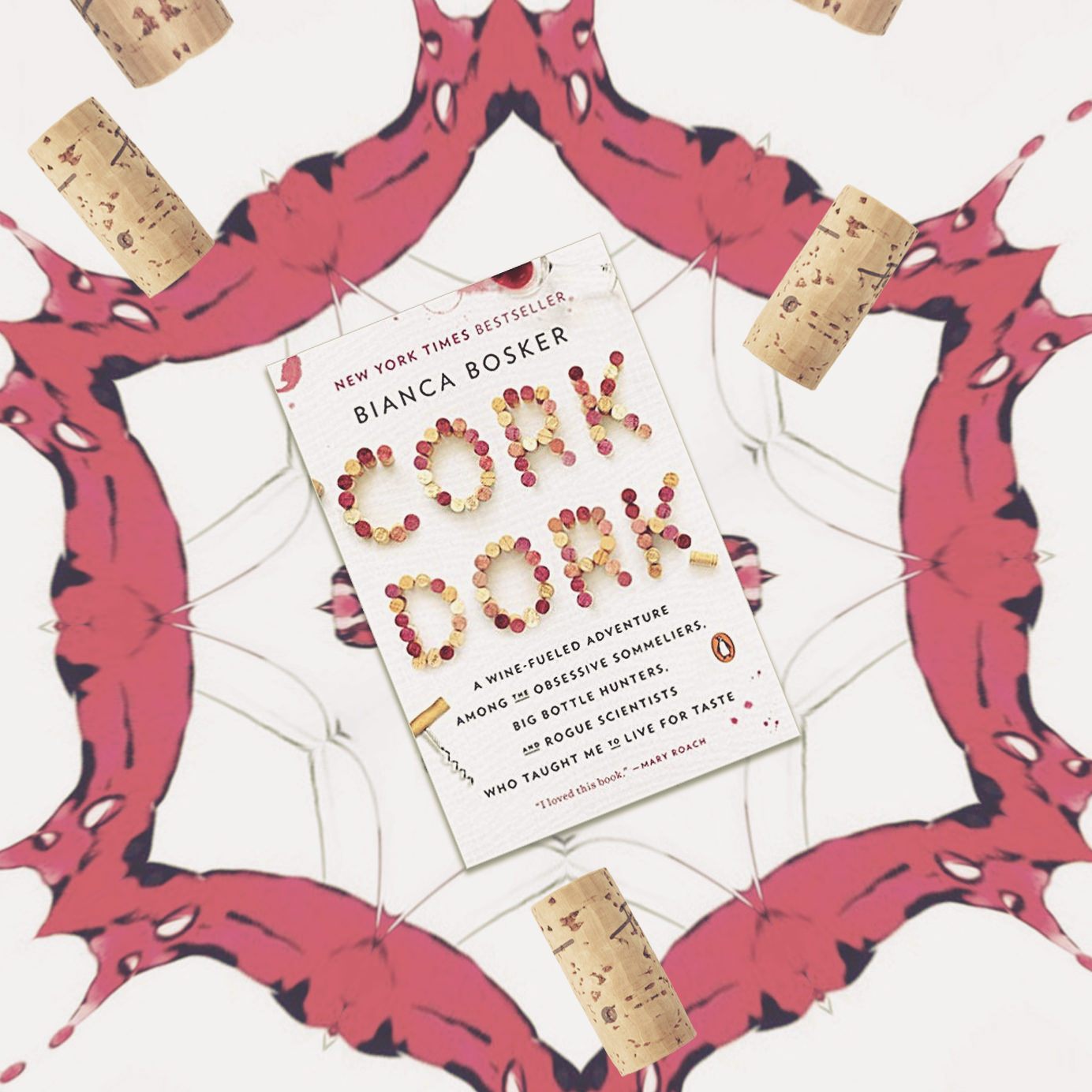

The wine world is up in arms over a new book. Bianca Bosker’s Cork Dork is a deep journalistic dive into the exclusive world of sommeliers, or “cork dorks,” as they call themselves. Already a New York Times bestseller, Cork Dork was hailed as “the Kitchen Confidential of wine” by wine writer Madeline Puckette. “Read this book, and you’ll never be intimidated by wine – or wine snobs – again,” Puckette wrote in a blurb.

But a backlash against the book appeared almost instantaneously, fueled by an op-ed Bosker wrote in the New York Times which bore the deliciously impetuous headline, “Ignore the Snobs, Drink the Cheap, Delicious Wine.”

In the op-ed, Bosker attacked one of the sacred cows of the wine industry – the idea that the fewer chemicals you add to your wine, the better. Bosker writes of one of the world’s largest wine companies, Treasury Wine Estates, which creates its mass-market wines by catering to the preferences of wine novices. Treasury manipulates its wines with chemicals until they’re perfectly suited to the tastes of the mass market, tastes excavated through focus group. It’s a practice deplored by many in the wine industry, but in her op-ed, Bosker argued that mass-produced, processed wines have their place in the wine ecosystem. “Connoisseurs consider processed wines the enological equivalent of processed foods, if not worse,” Bosker wrote. “But they are wrong. These maligned bottles have a place. The time has come to learn to love unnatural wines.”

The op-ed set off a host of passionate responses from industry insiders. “Bosker (and… Treasury, obviously) would prefer us drinking chemically infused alcohol juice than wines made by artisan growers,” wrote Marco Kovac in New Worlder. “Treasury and others of their ilk should run and grab this concept for a press release,” wrote Alice Feiring on her blog. “Its message? ‘So what if we load up wines with process and additives? We make wines of pleasure.’”

The brouhaha finally culminated in a series of tweets by Eric Asimov, the New York Times’s wine critic. “Big fan of @bbosker, but not buying the premise or the conclusion,” he tweeted. “I do think people who say they care about wine should be able to distinguish between processed and relatively unprocessed wines.”

Far from being put out by all of this, Bosker was pleased by it. In a recent interview, she called it “a really robust conversation.” “I’ve received so many supportive emails from distributors and thinkers and winemakers,” she said. “There are some people who disagree with me; I think that’s fine. I think it’s a very healthy and productive thing for the wine world to re-examine some of these inherited wisdoms.”

Some might consider those fighting words; not Bosker, who seemed to view the anger her op-ed ignited as confirmation. “One of the things that I found concerning about that reaction is that it speaks to this mindset of wine connoisseurs telling people what to taste,” she explained. “And one of the things that I hope to do with the book is to show people how to taste for themselves, because I think that is a much stronger foundation to create thoughtful drinkers than to say, ‘This is good wine, and this isn’t.’”

Is Bosker right? Was this backlash against her nothing more than a bunch of wine snobs disconcerted at having their snobbery exposed? It turns out, it’s not that simple. Despite the populism of the op-ed, Cork Dork’s focus on the most elite sommeliers and their rituals might just make wine more intimidating than ever.

*

I met Bosker at Terroir Tribeca, the site of a chapter in the book where she gets a job as a sommelier. In person, Bosker, who is just 30 years old, is beautiful, with big, soft brown eyes and a bluntly cut curtain of brown hair behind which she periodically recedes.

Bosker was raised in Portland, Oregon, by a professor of Russian language and literature and an E.R. physician. She was very nerdy growing up. “Could you tell?” she asked with a laugh. “I went to a very hippie private school,” she explained. “The biggest act of rebellion that one could do was not recycle. The biggest act of rebellion was being Republican.”

After high school, she went to Princeton, where she majored in East Asian Studies. There were a lot of 9 a.m. Chinese classes and a lot of flashcards with Chinese characters, foreshadowing the wine journey to be undertaken a decade later.

But there was very little kicking of hornets’ nests. “I was such a goodie two shoes, are you kidding?” she exclaimed. “I was not in any way a rebellious kid. It was always good grades, good SAT scores, and even in college, I never cut class.”

Bosker went on to serve as The Huffington Post’s executive tech editor until 2014, when she quit her job to find out “What’s the big deal about wine?” as she writes in the introduction to Cork Dork. To do so, she immersed herself in sommelier culture. But her goal soon morphed. A more “personal and profound concern quickly overshadowed my journalistic curiosity,” Bosker writes. “Merely writing about the sommeliers suddenly seemed inadequate. What I wanted, instead, was to become like them.”

Bosker proceeds to bring the flash-card discipline of her Chinese studies to wine, and in the final chapter, she presents us with her “A” grade — an fMRI scan shows that her brain has been altered. When drinking wine, her brain lights up like a sommelier’s, not a novice’s.

Cork Dork is an epic work of gonzo journalism, like if Joan Didion and Hunter S. Thompson had a baby who wanted to work in a restaurant. It’s a riveting read, full of science and service and gossip. From endless blind tastings to sommelier competitions to scientists’ labs to the front end of New York’s fine-dining restaurants, Bosker takes us from the armpit of the wine industry to the science behind it. It’s a dizzying tale, full of set pieces so vividly rendered you’ll feel like you’re being jostled by a wait staff trying to get around you, like you’re being dressed down by Paul Grieco, owner of Terroir Tribeca, livid that Bosker dared to contradict him in front of a guest.

Throughout, Cork Dork weaves science, data, and information into a narrative web so masterfully rendered that you feel like you’re reading gossip even when you’re reading about Plato’s contempt of smell. But contrary to Bosker’s claim, it doesn’t really question a lot of the wine world’s assumptions.

In fact, Cork Dork portrays learning about wine as a rather intimidating undertaking. Take, for example, two main characters who loom larger than all the others, neither of whom is in any way approachable. The first is Morgan Harris, a sommelier described to Bosker by other sommeliers as Rain Man, so intimidating do they find his encyclopedic knowledge of wine. In a chapter tellingly entitled “The Secret Society,” Bosker describes Harris as “borderline professorial, a tad hyperbolic, and extremely long-winded,” and treats us to entire pages of Harris’s breathless ruminations about wine.

The second character who helps shape Bosker’s view of wine is Paul Grieco, owner of Terroir Tribeca. Bosker calls him “Terroir’s mad genius creator,” and watches as he convinces guests at his wine bar to order a bottle of wine. “That is a wacked-out fucking journey!” He screams at them. “I’ll take you on that journey. You wanna go on a journey that’s a whacked-out fucking journey?”

While this approach is far from traditional, it’s hardly a re-examination of inherited wisdoms. If Bosker finds troubling the “mindset of wine connoisseurs telling people what to taste,” you could hardly find a better poster child for that approach than Paul Grieco, despite the casual wear and strange facial hair.

Harris himself worried about how he was portrayed in the book for a similar reason. “The person I am as a sommelier is not the person I am as Morgan Harris the wine lover,” he told me recently. As a wine lover, Harris knows he can be intimidating, which is why as sommelier, he takes great pains to tone a lot of that down, precisely to avoid alienating wine novices or intimidating them. Cork Dork focused too much on “Morgan the wine lover,” Harris told me. It’s a problematic portrayal of a sommelier, “because there’s too much me in it,” he explained.

Another sommelier I spoke to had a similar response. She felt that Cork Dork set her profession back, confirming people’s worst suspicions about sommeliers — that they’re snobs who are judging you and upselling you, whose primary goal is to get you to spend more money. “It just made my job a lot harder,” she said. Another sommelier told me he wouldn’t recommend the book to a wine novice. “It would scare you away,” he said. “It would make wine more confusing.”

Still, both of those sommeliers enjoyed the book — a lot. They admired Bosker’s writing, as well as the depth of her reporting, and the book’s scope. Another sommelier I asked about the book, Master Sommelier Brahm Callahan, admired Bosker’s ability to capture the life of a sommelier. “For someone who was trying to join, understand, excel, and summarize a world and set of senses that many of us spend our lives fine tuning, she was pretty dialed in,” he wrote in an email.

But capturing the life of a sommelier and capturing the beauty and joy of wine are not the same thing. For one person I spoke to, there’s actually a tension between the goal Bosker entered her project with — understanding what’s the big deal about wine — and the one she ultimately pursued — transforming herself into a sommelier. That person is Eric Asimov.

*

“In the last few years, we’ve kind of created a cult of the sommelier in this country,” Asimov told me recently over coffee. “I’m a huge proponent of sommeliers,” he went on. “I always recommend that people forget the apps — talk to the sommelier. But I resist the idea that the best way to get to know wine is to pattern yourself after a sommelier.”

Sommeliers have very specialized jobs to do, Asimov explained, whether it’s pairing wine and food, speed tasting, or identifying wines blind. “It’s not a model for enjoying and loving wine, in my opinion,” he said.

But it’s portrayed as such in Cork Dork. “One of the key elements of her book is learning how to taste wines blind, which to me is a parlor game, but is historically always misunderstood as a prerequisite for getting to know wine,” Asimov said. “For me, being able to identify a wine is a very different proposition from learning to love it and enjoy it.”

The whole notion of connoisseurship is a by-product of geographic locations that don’t make wine in the first place, Asimov argued. And when you focus on the way connoisseurs like sommeliers taste wine, what you end up doing is alienating regular consumers, because you convey that that’s the way you’re supposed to do it, and the way they are currently doing it is wrong. “That creates this sense of tension and anxiety that a lot of people I think experience,” explained Asimov.

Rather than mastering blind tasting and the arduous rituals of sommelier service, Asimov believes that teaching people to enjoy wine is about teaching them the role of wine. “It’s just a beverage,” he says. “It’s meant to give us all pleasure, and that is often sufficient, but then there’s so much more to it, so many more levels to it,” he explained. There’s the history, the people, the personalities. Good wine is an expression of culture, and it comes from a place. It has a past and it expresses the personality and character of a people and a region, especially in the Old World, Asimov explained. “These are the things that I find fascinating about wine and that are often lost in an effort to focus wholly on this collection of aromas and flavors that comes from a glass in a vacuum.”

Questioning blind tastings is a radical point of view, certainly a re-examination of some of the wine industry’s inherited wisdoms, despite Asimov’s elevated status. In his column and his book, How to Love Wine: A Memoir and a Manifesto, Asimov devoted his career to making wine more accessible and helping his readers embark on a journey of their own. In this context, Bosker’s journey in Cork Dork, which involved quitting her job and spending a year at 10 a.m. blind tastings with the highest-level sommeliers in the city, seems a lot less accessible as a starting point for novices wishing to learn about wine.

But Bosker disagreed with this analysis when I put it to her. “I think I say very explicitly in the book that you don’t have to quit your job and start drinking at 10 in the morning in order to get more out of wine,” she said. “To get pleasure out of wine, sometimes all you need to do is want a glass of wine. I think I say it very, very explicitly.”

“But for you, that wasn’t enough, right?” I pushed.

She explained that working as a sommelier in Terroir, she would sometimes get a table whose customers said, “Bring me anything, I can’t tell the difference.” And she’d bring them two or three wines and show them that yes, they could tell the difference. “I do see the book as my way of having the conversation that I would have as a sommelier maybe once, maybe twice a night, with tens or hundreds or, God willing, thousands of readers,” she said.

Bosker sees Cork Dork as empowering, offering her readers the very journey she herself undertook. “I had that experience and now I’m sharing it in the book,” she explained. Anyone can do it, she said, and the book shows you how. “There’s not a call out sidebar, like, Tip #47!” she said. “But I think it’s clear that there are things people can take away from it.” Like naming the smells of their shampoo, for example, or the smells on the sidewalks of New York. “Having reviewed the research, having gotten my own brain scanned, any of us can improve, any of us has what it takes to savor the stories we’re missing in a glass of wine, and here’s how to do it. I see it as very empowering to people,” she said.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BSoL9u_B66s/

But is chronicling an arduous journey to achieve a kind of knowledge the same as demystifying that knowledge for others? In another telling episode, Bosker asks Grieco what he looks for in a bottle.

“The wine must be yummy,” he tells her.

Bosker, quite understandably, asks for clarification: “Are there any particular… criteria that goes into yummy?”

“One sip leads to a second sip,” he says. “One glass leads to a second glass. One bottle leads to a second bottle.”

Grieco refuses to educate Bosker in what, according to him, makes a wine good. He chooses instead to keep that information to himself. It reminds Bosker of something Harris told her, after she asked him to explain what distinguished a $1,200 bottle of wine from one a twentieth of the price. “Like, God, America, SHUT UP. I don’t need to provide the answer to this question, because why don’t we have some goddamn mystery left in the world?” he demands. “It’s in your heart. It’s spiritual. It has nothing to do with quantification.”

And ultimately, Bosker comes to agree with this point of view. “Maybe that’s the thing about greatness,” she writes. “It defies formulaic expression.” There’s got to be mystery, she writes. “If greatness could be given by a formula, it would become trivial. But we know it when we taste it.”

Fair enough. But it would be a stretch to call this “showing people how to taste,” or empowering them. It’s quite the opposite, really; the idea that what makes a wine great must remain a mystery is literally an act of mystification.

Bosker doesn’t agree. To the contrary, she brought up more pedestrian tasting notes as an example of what she called the B.S. of the wine industry. She recalled an episode in the book where she spent months blind tasting with a group of sommeliers who claimed to be able to smell chervil in their wine. But those same somms couldn’t identify the smell of chervil when Bosker put some in a cup. Then there’s “minerality,” a word Bosker once told a patron at Terroir Tribeca never to say ever again.

“What I find very troublesome about that is, this is a language that we’re trying to use to make wine lovers out of people who are merely wine curious,” she explained. “And if we use these elaborate terms that have no real connection to reality, people will assume either they are broken or the wine is. I think it’s a really unhealthy starting point for a sustainable relationship with wine.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/BQlin_DhtZq/

Rather than talk about the chervil in a wine, or something as pedestrian as floral notes, Bosker subscribes to a more metaphoric take on tasting notes. Morgan Harris once told her that Nebbiolo was like “male ballet dancers.” “And I was like, I want to try that!” Bosker remembered. Another time, he called a Chardonnay “the face that launched a thousand ships.” “I have no idea whether that tastes like apple or pear or Meyer lemon, but I don’t give a fuck! I want to try whatever crazy wine it is!” Bosker remembers thinking. “If you’re trying to inspire someone to go on this journey with you, then I think it’s O.K to use these more evocative tasting notes,” she explained.

She had been excited when the sommelier who waited on us at Terroir asked me what kind of wine I was looking for. “Be vague, general,” he said. “Let’s talk about what kind of animals you like. Free associate.”

But at the end of the day, describing a wine as a male ballet dancer, or pairing a wine to a drinker’s favorite animal, is as alienating if not more alienating than saying it has aromas of Meyer lemons, or chervil. Like a parlor trick, it keeps the drinker in the dark, ultimately widening the gap between drinker and sommelier.

Bosker was trained by Grieco to serve as a sommelier in this fashion, and it’s how she operated on the floor of Terroir. When the sommelier brought me an admittedly delicious Barolo, Bosker called it a “black stallion of a wine.” “If Black Beauty was a wine, it would be that wine,” was how she said she would have sold it at Terroir.

Her description was a lot like Cork Dork – a gorgeous, deliciously rendered little journey for my mind to follow along with that, when all is said and done, remained entirely Bosker’s.

*

Despite its failure to demystify wine, it’s impossible to read Cork Dork without learning a whole lot about wine, and wanting to learn much, much more; it is therefore a huge accomplishment. Even people who criticized the book admitted to enjoying it. Asimov, too, found it entertaining, and appreciated the strength of the writing. But he also found it to be symptomatic of a larger, very conventional, very American point of view. “You need a diploma,” was how he summed it up. Or, perhaps, an fMRI scan showing you’ve officially turned your brain into that of a connoisseur.

When you read the book as a love song to the cult of the sommelier, rather than a demystification of wine, the New York Times op-ed makes more sense. If the way to truly appreciate wine is to become a sommelier, why shouldn’t the rest of us — who are not lucky enough to quit our jobs and blind-taste wines all day — just buy the cheap, manipulated stuff that’s generated purely for our terrible taste?

Of course, this is not what Bosker meant to say. Bosker believes these manipulated wines can be a starting point for a wine journey, that they can spark curiosity rather than slake it. For that, though, I wouldn’t recommend Treasury’s wines. I’d recommend Cork Dork. I just wish Bosker could embrace the snobbery at its heart.