The light striking the courtyard’s sandstone walls gave a golden haze to the evening. Guests seated at wooden benches chatted quietly, enjoying plates of fresh summer food.

But there was nothing welcoming about the server. “There is nothing wrong with the wine,” she said, loudly enough for heads to turn.

My boyfriend and I had just arrived in Germany and were having a romantic dinner. I’d ordered a glass of Spätburgunder, the local Pinot Noir.

But when I raised the glass, all I smelled was moldy dishrag. It wasn’t exactly like TCA, the compound responsible for cork taint, but what else could do that to a wine? I quietly asked for another glass.

“If you want another, you’ll have to pay for both,” said the woman.

I felt my face flush. “It’s corked.”

She marched back into the bar at a rapid clip and came back, bearing the bottle. It had a screwcap, not a cork.

“There is no cork taint in that wine,” she said. By now, everyone was staring. We finished our dinner at top speed, feeling the sting of public humiliation. When the bill came, it included the musty red wine, as promised.

Later, a wine writer told me that the wine came from a difficult, wet vintage. “Some people bottled rotten grapes,” he said.

Coming from Australia, where wineries pride themselves on technical perfection, it was a shock. But in the next few years, I encountered lots of wine problems, particularly at European wine competitions, where many wines with “off” smells or flavors would appear.

That was 14 years ago. Since then, world wine quality has skyrocketed to the point that faulty wines are rare. Not only are even the cheapest wines well made, there’s a stunning diversity of styles and grapes available.

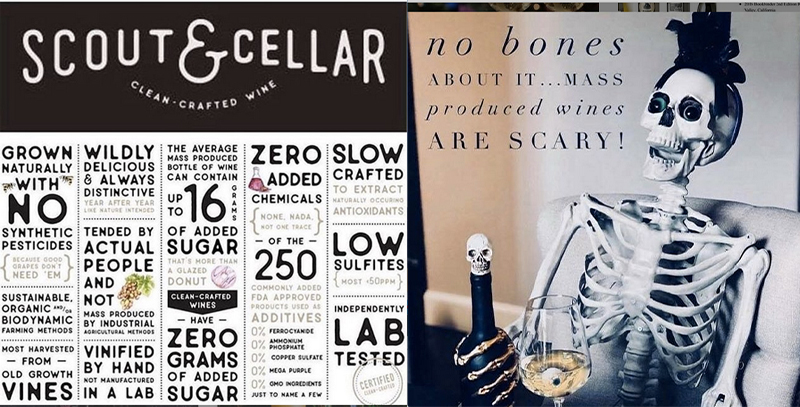

Yet at the very moment that wine quality is through the roof, ads are appearing across social media claiming that wine is suspect. “Clean wine” marketers compete to create memes about how terrifying wine is; one will post that people should count chemicals, not calories, and the next will claim that wine has “250 commonly added additives” (false). My favorite is the skeleton clutching a wine bottle. “Mass produced wines are scary!” says the caption. Over on Facebook, ads show white sugar being dumped into a wine glass.

Where are all these lurid wine tales coming from?

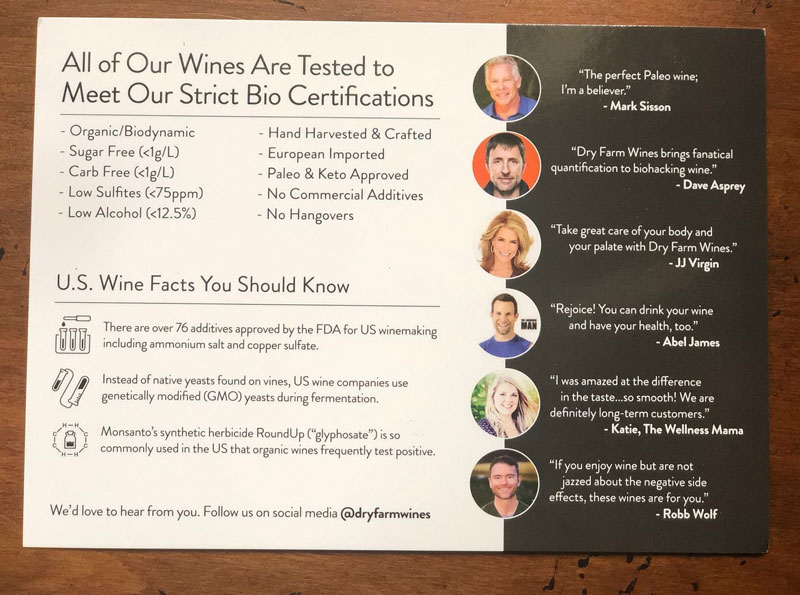

A dive into social media reveals they’re coming from people with wine to sell; on Instagram, the memes are often the work of Scout & Cellar consultants, who take a commission on the “Clean-Crafted” wine they sell. The Facebook ads showcasing wine glasses with sugar are from Dry Farm Wines, an online store selling natural wines.

It’s marketing by disparagement, but the claims are difficult to rebut because of Brandolini’s Law: “The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it.”

But here goes.

The first way to cast doubt on something is to position it as all or nothing. Here, the implication is that if you’re not drinking their wines, then you’re drinking industrial, factory-made products. These marketers avoid mentioning that wine is a joyfully diverse category, offering everything from homogenous, focus-group-tested products to handmade, artisanal wines — and everything in between.

Second, while wine is a natural product, it’s also a marvel of complex chemistry. Because most people associate chemistry with industrial sorcery, it’s easy to freak them out by calling something by its scientific name. Wine lovers who are used to hearing about beneficial chemicals like polyphenols can be shocked by references to diammonium phosphate — until they find out its other name is “yeast food.”

ADDITIVES

So how many additives are there? If you include processing aids, which don’t stay in the final wine, there are 69, including elements found naturally in the grape. The register is being updated right now; some vegan fining aids are being added. Ferrocyanide, which Scout & Cellar claims is a common additive, is being removed. Not only does nobody use it, it’s not even available on the market.

Just because something is listed doesn’t mean it’s used, because winemakers prefer to let the grapes speak for themselves.

SUGAR

Another way to introduce doubt about any product is to claim it’s full of added sugar.

There are only really two times when sugar can legally be added to wine. The first is chaptalization, when limited amounts can be poured into fermentation vats to get higher alcohols. The technique was traditionally used in cold climates like Champagne and Burgundy, but it’s becoming redundant thanks to climate change. Chaptalization is illegal in California.

Sugar is also added by anyone using the Champagne method to make a sparkling wine; along with yeast, it’s what gets a secondary fermentation going. Otherwise, sugar can’t be added.

MEGA PURPLE

One ingredient that is legal in California is grape concentrate, which adds sweetness and color to red wines; using ‘teinturier’ or black-juiced varieties like Alicante Bouschet to add color is a very old technique that was still used in Europe in the 1970s.

Today there is a commercial concentrate available called Mega Purple, which has become a shorthand for mass-market, confected red wines; it’s not a winemaking tool that serious winemakers use, and it’s illegal in EU appellations, where nothing can be added to change the essential nature of the wine.

COLOR DYES

Adding dyes to wines? Illegal.

SULFITES

Sulfites are used to preserve and protect wine from bacteria, spoilage, and oxidation. While the legal limit in the U.S. is 350 milligrams per liter, the average is well under 100 milligrams per liter. According to Wired, the FDA identified sulfites as an allergen in 1986, “and that’s how the hysteria over sulfites in wine started,” with people blaming sulfites in wine for headaches; no definitive link has ever been established.

PESTICIDES

Pesticides — both synthetic and the copper sulphate used by organic growers — are indeed sprayed on grapes to prevent rot and mildew; the application and timing are regulated to ensure as little residue as possible by the time the fruit is picked. One of the world’s biggest wine buyers, the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, has its own laboratory and tests every wine that enters the province for heavy metals and pesticides. Thousands of these wines come from the United States, including many of the big, commercial wine brands. “From the 22,600 wines tested in 2019-2020,” a press officer wrote to me, only 20 exceeded the LCBO’s limits. For the math uninclined, that’s less than one-tenth of 1 percent — hardly skull-and-crossbones-worthy quantities.

GMO YEASTS

Dry Farm Wines claims: “Instead of native yeasts found on vines, US wine companies use genetically modified (GMO) yeasts during fermentation.” While GMO yeasts are illegal in the EU, there are two GMO yeasts that winemakers in North America could theoretically use — except that neither is on the market any longer. The man who developed them, Professor Hennie van Vuuren of the University of British Columbia Wine Research Centre, is now retired. He wrote to me that he engineered one of the yeast strains to “prevent the production of ethyl carbamate, a carcinogen present in wines,” and the other to prevent the production of allergens during fermentation, because “I am allergic to bioamines in wines and I love wine.”

ALCOHOL

Dry Farm Wines might claim that its wines are “Hangover-Free,” but no such thing exists. If it’s wine, then it’s capable of giving you a hangover if you drink too much. That’s an undisputed fact.

ALLERGIC REACTIONS

Biogenic amines, the compounds almost single-handedly responsible for most wine conspiracy theories, are sometimes produced as a byproduct of fermentation — ironically, the thing that can stop them is sulfites.

Many people who get involved with “clean wine” companies tell origin stories that go like this: They used to drink wine with no problem, until they suddenly noticed that a single glass or two was making them feel sick and headache-y. After reading up about winemaking, they realized it was all the additives and toxins in the wine making them feel lousy — and they then resolved to start selling pure, clean wine (sound familiar?).

The true culprit is generally either the alcohol or the biogenic amines, one of which is histamine; others include the fabulously named putrescine and cadaverine. They’re also found in some foods, like charcuterie, cheese, vinegar, spinach, and tomatoes, among others, and it’s the cumulative effect of ingesting them that causes problems.

“The way I describe it to consumers is that you have an internal limit or threshold for a chemical compound such as histamine — everybody’s threshold is different,” says pharmacologist Dr. Creina Stockley of the University of Adelaide in Australia. One day you might be eating food with histamines and feel fine, “but on the second day, you have a glass of wine which raises your level of histamine above the threshold, and you can feel unwell. Because wine was the last food you were exposed to, you automatically blame the wine.”

The real problem with wine isn’t that it’s full of toxins (apart from alcohol) but that there’s almost nothing on the label to indicate how it’s been made. This will change in the next five years, as ingredient labelling is coming to the EU by end of 2022, which will push other wine-producing countries to follow suit.

In the meantime, anybody interested in low-intervention wine has a whole world of artisanal and natural wine to choose from — and you don’t have to buy them from someone using scare tactics as a sales technique. If anybody approaches you trying to sell you “clean” or “clean-crafted” wine, ask them to tell you exactly how it was made. Because if it’s not a natural wine, then it was made using additives — and if they can’t tell you what those are? They have something to hide.

To get hold of a bottle of delicious, low-intervention wine, just ask your local independent retailer for recommendations. If there really is something wrong with the wine, like cork taint, you have the right to take it back. But the chances of a bad bottle are, fortunately, extremely rare these days.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!