“No one brings beer to a dinner party,” a colleague recently said to me. I was shocked. (I do!, I thought.)

But he was right. Most people don’t. They bring wine.

A recent survey from the Beer Institute revealed that only 16 percent of adults aged 21 to 24 who drank alcohol in the last month consider beer “special,” and just two percent see it as “sophisticated.” Wine, on the other hand, was deemed special and sophisticated by nearly 40 percent of respondents.

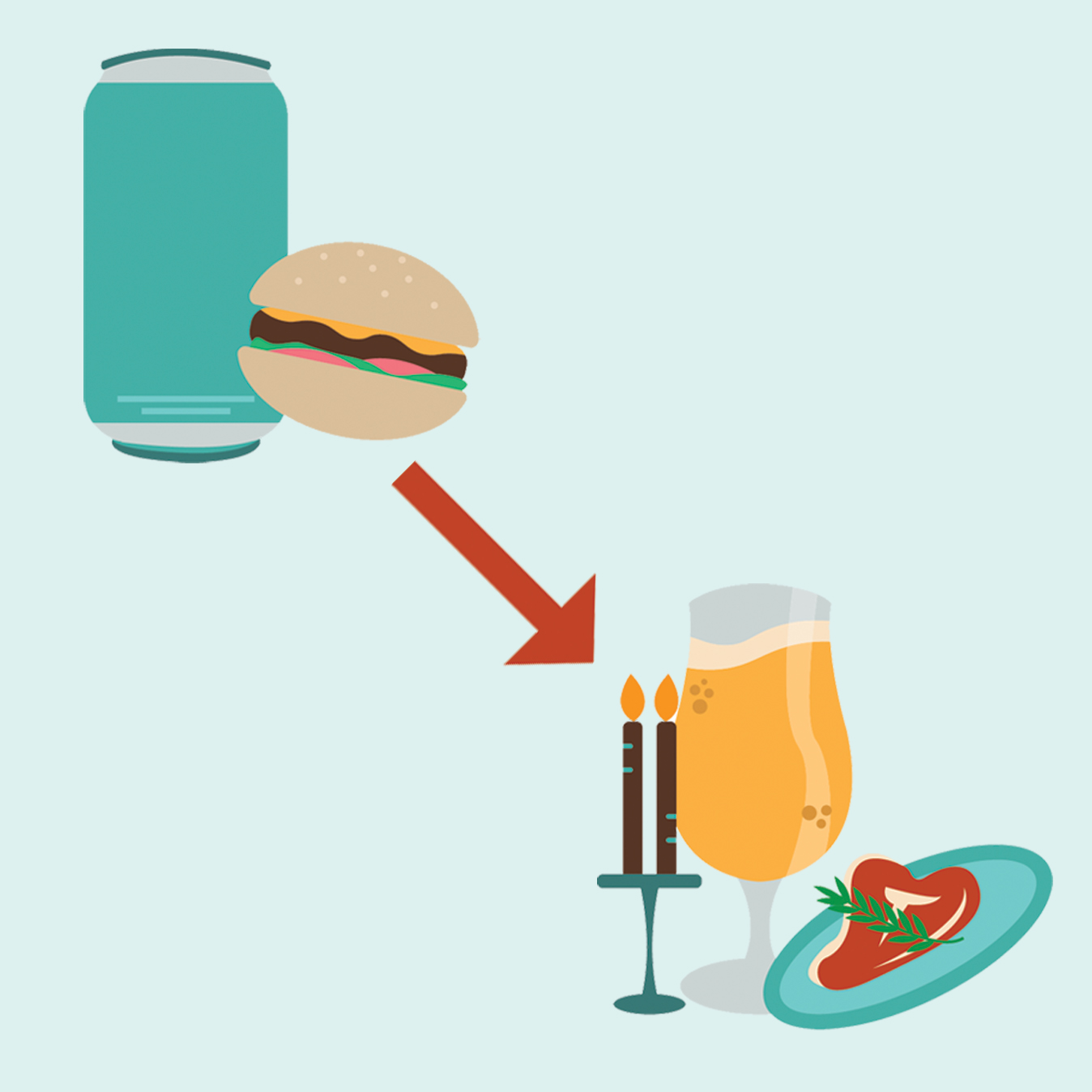

The messaging is clear: Wine is classy, beer is common. Wine is fancy, beer is casual. Wine deserves glassware and white tablecloths; beer pairs with barbecues and plastic cups.

This is slowly starting to change.

Brewers, beer educators, and geeks like me are making a concerted effort to bring beer to the table. First came the Cicerone Certification Program, a process intended to mirror the wine industry’s sommelier certification. The Cicerone program is a multi-level course that educates students in beer styles, service, and pairing.

The Cicerone program has certainly been valuable. But the future of beer and food pairing is not Cicerones. It’s not competing with wine, either. It’s being wine.

The most vocal advocate for beer and food pairing might be Julia Herz. As the Brewers Association’s craft beer program director, and herself a Certified Cicerone, Hertz piloted the CraftBeer.com Beer & Food Course with a Culinary Institute of America graduate and a Certified Cicerone. She also helped organize Savor*, an annual beer and food festival that takes place in Washington, D.C. in June.

This year marked the 11th annual Savor, at which some 90 breweries served beers alongside elevated hors d’oeuvres. (Think barrel-aged sours and swordfish crudités instead of IPAs and pretzel necklaces.)

Richard Norgrove Jr., owner and brewmaster of Bear Republic in California, says his family business focused intently on beer and food pairing from the get-go.

“That model of opening up in a warehouse and pulling a taco truck outside wouldn’t have worked 23 years ago,” Norgrove says. Bear Republic, which currently operates a brewery in Cloverdale and two brewpub locations in Healdsburg and Rohnert Park, is within three of Sonoma’s major wine growing regions: Alexander Valley, Dry Creek Valley, and Russian River Valley.

“There are so many good epicurean locations in our town that you can’t be just be a regular brewpub,” he says.

Norgrove says all Bear Republic employees are encouraged to complete the Cicerone program, along with the brewery’s own internal “beer 101” training program, to better showcase its beer as equal to wine.

“Instead of trying to compete against [wine], we’re trying to complement it,” Norgrove says. Bear Republic has won several awards for its wine selection. “For many years we were the anomaly.”

The Brewer’s Table, a new brewery and restaurant in Austin, Texas, is putting a high-end, beer-soaked slant on its culinary program as well. Its menu highlights beer and food pairings and incorporates beer into its recipes with inventive ingredients like vegetables picked in wort, dried yeast pepper (black pepper with brewing yeast), hop salt, and raw beer for finishing sauces.

“Obviously we’re all aware of wine programs’ role in traditional restaurants, for all of time pretty much,” Zach Hunter, executive chef at The Brewers Table, says. “There’s almost always been a wine list, wine cellar, and sommelier. You don’t ever see that with beer.”

Hunter and his colleagues hope to change that. He has worked at Michelin-starred restaurants like Mugaritz in Spain and Atera in New York City, and most recently he was chef de cuisine at Fixe in Austin.

“I hope that we can set a tone and inspire those around us to adopt these programs into their beverage programs,” Hunter says. “It makes for a more dynamic experience. By having both beer and wine, we’re able to capture a wider audience and really create an experience that can be for everyone.”

At the Brewer’s Table, front-of-house staff are required to study in the Cicerone program to become certified beer servers. Hunter estimates about 90 percent of his kitchen staff is also certified.

“It gives them a better understanding as cooks of the ingredients of beer, the different nuances and styles, why we choose different beers to cook and pair with,” Hunter says. “On the floor, it gives them a great opportunity not only to recommend great beers to go with our food, but to really give guests an experience they wouldn’t be able to find somewhere else.”

But even the best brewpubs and gastropubs are, for the most part, not hiring Cicerones. While sommelier certification is a requirement for many wine careers, beer industry vets aren’t seeing as much of a need for beer serving certification.

In fact, for some, the concept is maybe a little cheesy.

“It’s kind of like going to bartending school. You don’t have experience, you just have a piece of paper,” says Tristan Colegrove, bar manager at Haymaker Bar and Kitchen, one of New York’s most popular gastropubs. “Running this business, I haven’t run across too many people who have [it] on their resume.”

If he did, he’d be less than impressed. “It shows interest but it doesn’t really show they know that much about beer,” he says, adding that “any one of us could pass it blindfolded and probably piss drunk.”

Anne Becerra, the celebrated first female Certified Cicerone in New York City (and still one of very few), runs the beverage program at Manhattan’s Treadwell Park and even brought the city its first beer cellar. She also teaches classes at the Culinary Institute of America and elsewhere. Yet she too hesitates to champion the Cicerone designation.

Although she believes beer servers should maintain a certain level of professionalism, she doesn’t see becoming a Cicerone as the golden ticket. “Passing a test [is not] going to mean you have the same level of knowledge as someone who’s been in this industry day in and day out,” Becerra told me in an interview last year. Cicerones are schooled on beer styles and draft systems, but things like “fixing problems in the middle of a service rush and knowing all your distributors” can’t be learned in a classroom, she says. “Just because you passed [a test] doesn’t mean you’re an expert.”

If not expertise in service, what the certificate does show is something perhaps more important in the grand scheme of things: interest. “[Certified beer servers] know the basics, which is a lot more than the general population,” Colegrove says. “I do see it on people’s Instagram and threads of conversation [online] more than I see people applying to my bar with it.”

Heather McReynolds is a social correspondent for Guinness, a former brewer, and also a Certified Cicerone (she does, incidentally, include the designation on her Twitter profile). She has shifted her perspective on the Cicerone program since leaving brewing behind for a corporate setting.

“I use what I’ve known [as a brewer] and what I’ve studied as a Cicerone to help people who are reaching out to me on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook learn more about beer,” McReynolds says. Previous stints include brewing at Sixpoint, as well as managing a beer bar and brewpub in Florida. She believes that having conversations with people interested in beer is “the best thing we can do to help elevate beer overall.”

Cicerones have a place, but it’s not on the floor. It’s on social media, in classrooms, and at corporate offices where they can position themselves as beer experts. Three of the world’s 16 Master Cicerones work for Anheuser-Busch InBev, whereas countless talented brewers and beer executives learned by doing, not via certification coursework.

“It’s not quite relevant yet, but that doesn’t mean it’s not going to be,” Colegrove says. He’s not sure what the next five years hold for Cicerone certification, or for himself.

“I hope I’m not running beer bars then,” he laughs. “I hope I have something that makes me a lot more money, like a fast casual taco stand.”

*VinePair was the 2018 media sponsor for Savor.