Chile’s geology and climate are perfect for making wine. With the ocean on one side and the Andes on the other, Chile’s vineyards get the benefit of salty winds and cooling airs, plus wide day-to-night fluctuations — perfect conditions for grape growing. And yet, up until the mid-’80s, the wine produced in Chile was by all accounts pretty awful. It was made by Chileans for Chileans, mostly from a grape called pais, or Mission, and barely any of it was exported. Chileans themselves were drinking less wine than ever, and by the 1980s, half of the vineyards had been uprooted. In 1985, the entire industry was valued at a scant $11 million. But all that was about to change.

Around that time, a young winemaker named Aurelio Montes was working at a Chilean winery called Viña Undurraga. But he yearned for more. “I felt that Chile deserved more than what it was getting,” he told me recently in his home in Santiago. “I wanted to show the world that there was the chance for good wines and I wanted to grow in life and give a better life to my family.”

I met Montes on a press trip to Chile. Tall and erect, with staggeringly blue eyes and a warm smile, Montes is impossibly charismatic, one of those rare people who can captivate a room full of people while also putting them at ease. Sitting on an enclosed patio in his Santiago home, Montes told me how he eventually left Undurraga to start his own winery, Viña Montes, with three partners (it was his winery that sponsored the trip).

Montes is now 70 and considered to be one of Chile’s most experienced and respected winemakers, according to Wine Spectator. Today, Viña Montes produces 680,000 cases of wine a year, with 92 percent of sales from export markets. Montes’s wines have won awards, with scores in the 90s from the likes of Wine Spectator. But it’s not just Montes who is producing fine Chilean wine. Along with a few others, Montes brought Chile into a new winemaking era. In just three decades, Chile had transformed into a recognized destination for fine wine. What’s more, as of 2010, Chile was exporting over 70 percent of its wines – a higher percentage than any other country in the world. In 2013, Chile exported almost 900,000 tons of wine. The industry is currently valued at $1.9 billion – in no small part due to Montes’s vision.

“I always compare myself with a surfer,” Montes explained. He’s sitting on a surfboard and sees a big wave coming — but no one else sees it. “And I jump to the table and I surf the wave, all the way to the beach,” he says. “That’s more or less what happened. Everyone else was looking somewhere else. I was looking at the wave.”

But though Chile’s flourishing wine industry is indebted to the vision of people like Montes, this is not the only source of its splendor. In fact, Montes’s metaphor of being a surfer is more apt than he may even realize. For in addition to his vision and his willingness to take risks, there were social and political currents that enabled Montes to succeed as he did. Indeed, that wave he rode had a name. And its name was Augusto Pinochet.

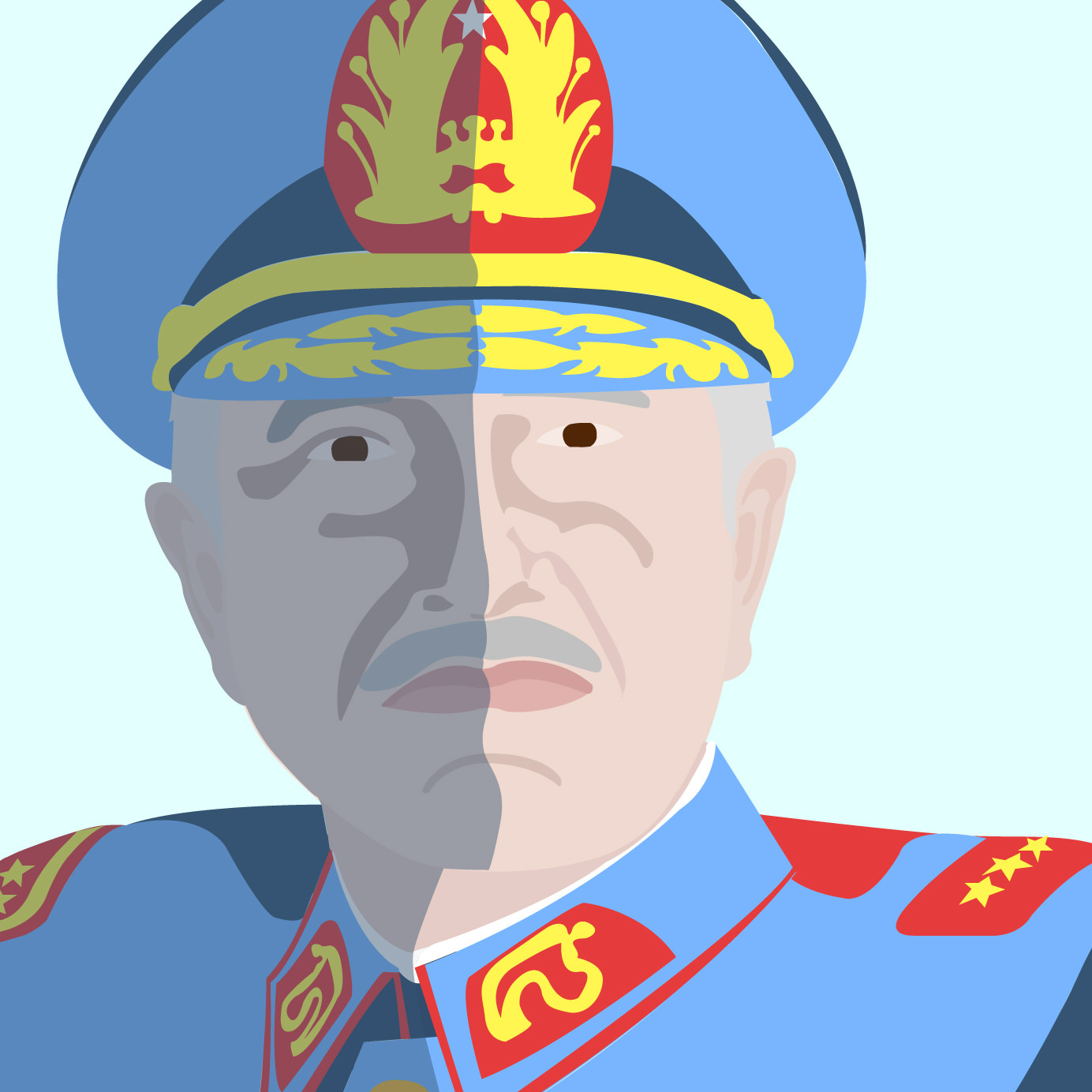

Pinochet was the brutal Chilean dictator who ruled Chile for 17 years, from 1973 to 1990. His reign included the torture and disappearance of dissidents and the silencing of political opponents and the free press. But Pinochet’s reign had a curious side effect: The dictator revealed himself to be committed to free-market principles, principles that would prove crucial to Chile’s emerging wine industry.

In fact, the story of Chilean wine may embody one of the central ironies at the heart of Chile’s recent past. Could it be that a dictator who opposed all forms of political freedom and killed, tortured, and exiled his opposition, would end up implementing market conditions for a flourishing wine industry? Was Pinochet good – even essential – for Chilean wine?

*

The seeds of Chile’s wine revolution were planted back in 1970, when a majority of the Chilean people voted for the socialist politician Salvador Allende as their president. Not everyone was pleased with the new administration. Chile’s elites feared what a socialist president might have in store for them. They were right to fear him, too; Allende nationalized large industries like Chile’s copper industry and its banks. But even worse for Chile’s elites was the land seizure and redistribution. Between Allende and his predecessor, Eduardo Frei Montalva, the great estates of the landed property system were expropriated from the Chilean elites, placing them in the hands of the state, explains Antonio Bellisario, a professor in the Department of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences at Metropolitan State University of Denver who has written about the subject.

The idea was to redistribute these assets among Chile’s working classes. But Allende’s plans faltered, and by 1972, the Chilean economy was in free fall. Food shortages led to people standing in line for bread, and in 1973, a military general named Augusto Pinochet led the army in a successful military coup, or junta, against the Allende government. Barricaded in the presidential palace, Allende ended up dead, most probably by his own hand, and Pinochet installed himself as a military dictator.

From the get-go, Pinochet’s new military dictatorship was a violent affair. Thousands of people were killed; 30,000 people were tortured. Almost 4,000 people disappeared without a trace. But the closing down of political freedoms came with a curious side effect, thanks to an exchange program between the Catholic University of Chile and the University of Chicago. The U of C’s economics department was famous for one of its professors, Milton Friedman, who advocated small government and deregulated markets as the path to economic prosperity. The Chilean students educated at the University of Chicago came to be known as the “Chicago Boys,” and they brought Friedman’s convictions back to Chile with them.

When Pinochet came to power, he didn’t have an economic platform, explains Professor Javier Nuñez, an economist at Universidad de Chile. The Chicago Boys saw an opportunity; using the principles they’d learned at school, they convinced the dictator to reduce the size of the government and end restrictions on trade.

It took a while for these new policies to really bear fruit in the markets. First there had to be a reshuffling of labor and capital between the public and private sectors, and then between economic sectors, from protected sectors to natural resources, explains Professor Nuñez. This took time. And there were a number of international recessions in the ’70s and ’80s that hit Chile hard and resulted in high unemployment and a freefalling GDP.

But eventually, things settled down, and today, Chile has the strongest per capita GDP in Latin America.

*

Not everyone sees things this way. Some, like Wendy Brown, a professor of political science at UC Berkeley, disagree that the Pinochet government, even its economic aspect, presents a net gain for Chile. Unemployment grew. There was a currency disaster that plagued Chile through the ’80s and ’90s. “So if what people mean by, ‘It was good for the economy’ is that it generated a higher rate of wealth production, yeah it did,” Brown says. “Did it distribute it widely to the people? No. Did it produce stability? Absolutely not. When it comes to economic measures, you get to choose the ones you use,” she went on. “People who praise neoliberal rates of growth cannot defend the growing disparities between the rich and the poor.”

As for the food lines under Allende’s administration, what came next was much, much worse. “What followed was rounding up tens of thousands of human beings and shooting them,” she says. “Take your pick.”

But most Chileans separate Pinochet as a dictator from the economic regime he implemented, says Nuñez. Most Chileans acknowledge that Pinochet abused human rights, killing, torturing, and exiling people; but at the same time, they insist that the economic policies he implemented in terms of opening the economy were inevitable and good for the country.

And some are not ambivalent at all. At Viña Montes’s Apalta winery, I spoke with some women who were sorting grapes. One of them, a short woman with black eyes and a bright smile, told me that she had worked on the property before it belonged to Montes when it was just a farm. “I’m as part of this place as any of the bricks,” she told me through a translator.

She and the other workers I spoke to were all staunch Pinochet supporters. They felt safer under the dictator’s rule. “Back in those days, you could walk down the street and no one would try to hurt you or try to do you any harm,” she said. “Now it doesn’t feel quite like that.”

I asked if she knew anyone who had been tortured, or exiled, or killed. She and the other women laughed. “The truth is, no,” she told my translator. “But you can’t talk about it. Because supposedly everything that happened during those times is bad. But it wasn’t bad for us, here. It felt good, safe.”

And they didn’t miss the right to vote during that time, either. “We couldn’t vote, but things are not as bad as they are usually told in history,” the woman explained.

Another person I spoke to, Daniel Greve, is a food and wine writer who runs a company called Imporio Creativo. “I think Pinochet was maybe good for some things in an economic way, very bad in other ways, the same as, you know, Allende,” he told me.

Greve is from Santiago, and his parents were pro-Pinochet. “Because they suffered a lot with the Allende thing, no food, the queues,” he explained. But his neighborhood, like much of Chile, was very mixed. Greve remembers conversations between his parents and their friends where they would debate the pros and cons of Pinochet’s regime.

One winemaker I spoke to seemed to symbolize the tension at the heart of Chilean society. His family had benefited from the junta because his father’s business had been nationalized by Allende. But his wife had the opposite story: Her three uncles had been diplomats in Allende’s government and had been exiled to Australia.

Pinochet’s reign ended in a referendum in 1988, in which 55 percent of the population voted him out, meaning that 44 percent wanted him to stay. But the only person I met in Chile who unapologetically reviled Pinochet worked at the Pablo Neruda Museum. Neruda, Chile’s most celebrated poet and Nobel Prize winner, was also a big Allende supporter. He died just days after the coup, possibly at the order of Pinochet.

The young man working behind the counter at the gift shop had an uncle who had been disappeared by Pinochet and who was still missing. When I asked him about the positive effects of Pinochet’s economic policies, he said, “They say the same thing about Hitler.”

*

It’s not surprising that the people I met during my trip – wine industry people – were Pinochet apologists. Perhaps no industry was as affected by his economic transformations as the wine industry. Under Pinochet, tariffs on international import and export were reduced. Pinochet ended laws against foreign investment. Steel tanks were introduced to Chilean winemaking for the first time, explains Bill Crowley, Professor Emeritus at the Department of Geography and Global Studies at Sonoma State University. “They had more or less had great difficulty importing new winery technology until after Pinochet’s coup and his new pronouncements,” explains Crowley.

Pinochet recognized Chile’s geography as a huge competitive advantage, and under his rule, agriculture increased, as did fishing, forestry, and, especially, wine.

But Pinochet wasn’t the only one to recognize the favorable conditions. A lot of entrepreneurs saw the possibilities for producing good wine in the Chilean climate, with its dry summers, its wet winters, and the moderating effects of the Andes mountains. “They saw the potential and went for it and it worked,” Crowley says.

It wasn’t only Pinochet’s policies, says Bellissario. Remember that land that Allende had seized from the landed elites? It now belonged to the government. When Pinochet took power, he gave a third of the land back to the landowners, and redistributed the rest among the peasants. But without the requisite tools, they couldn’t manage their own properties. It became a Darwinian system where most of the peasants were forced to sell the land, dirt cheap, to bidders of the government’s choosing. Suddenly there was cheap Chilean land available for sale to foreign investors or upper middle-class business people.

“They auctioned them off and created a new class of entrepreneurs,” says Bellisario. “They sold it back only to landowners who wanted to use the land for capitalist economic purposes.” Like winemaking.

*

Aurelio Montes’s story runs parallel to Chile’s larger wine story in more ways than one. Born in 1948, he came from modest beginnings, the youngest of four children. His father worked in insurance. “We had enough for a decent life, good schools, a car, and that was about it,” he told me. “So we were not rich at all. There was nothing missing but nothing in surplus at home. We had what we needed.”

Montes had just left university when Allende assumed power. He was 21 years old, and eager to start working and build a career for himself. But he felt stymied by the economic conditions he found around him. “It was a real mess,” he remembered. “I was in charge of the unions in the company that I worked. And after 2 p.m., I couldn’t talk to them — they were all drunk.”

Montes feels strongly that Allende took Chile in the wrong direction. “He was the worst government in Chilean history,” he said. “We didn’t have food. We had to make a queue to buy bread.”

Things got worse. Montes’s wife’s family owned a farm and some land, and it was expropriated and nationalized. Lots of his peers left the country, but Montes never even considered it. “I told my wife, we will stay here, we will fight for Chile, we will be part of what’s going on here,” he said.

Montes got his job at Undurraga right after he left university, and worked there up until the ’80s. But after 12 years, he grew dissatisfied with his prospects. “I reached a ceiling, because I was not an Undurraga,” Montes told me. “I got to the highest level I could without being a member of the family.”

A friend, Alfredo Vidaurre, convinced Montes to leave Undurraga. Vidaurre was an economist working with a Chilean banking group that had recently purchased a winery, and he wanted Montes’s expertise at the helm. But instead, along with Pedro Grand and Douglas Murray, Montes and Vidaurre founded their own winery, Discover Wines, in 1988, changing the name soon thereafter to Viña Montes.

With his 16 years as a winemaker behind him, Montes knew exactly where to get the best grapes in Chile. With a $62,000 investment from Vidaurre, they started to buy tiny amounts of grapes and borrow space in other wineries to make wine. It was tough going at first. “We didn’t have a penny in our pockets,” Montes told me. He had five children, and no steady income; it was a scary time. But Montes’s vision was a powerful one, and today, Viña Montes has 700 hectares under vine in Colchagua and Zapallar.

But Vidaurre, who died in 2008, was not only seizing opportunities offered by the policies of the Chicago Boys. Vidaurre was one of them. After college, he won a Rockefeller Foundation scholarship to the University of Chicago, to study economics. Vidaurre returned to the Catholic University to fulfill the terms of his fellowship, and became the youngest ever Dean of the Faculty of Business Administration and Management.

This was still during the Allende years. “Chile cannot have been the easiest of environments in which to teach business after the election in 1970 of the Marxist President Allende,” writes Jamie Ross in Where Angels Tread: The Story of Viña Montes. “It was not so much socialism, as all-out class war,” Vidaurre told Ross. Vidaurre left Chile just weeks before the junta, and returned four years into Pinochet’s regime to join the banking group BHC as head of investments. About a decade later, he and Montes went into business together.

It’s inarguable that the Pinochet years resulted in better wine for Chile and for those of us who love great, affordable wines. If there had been no military dictatorship in Chile, there would be no Chilean wine industry as we know it – about that all the economists I spoke to agreed. But it took the vision and innovation of winemakers like Montes to turn those opportunities into gorgeous wines like Montes’s celebrated Purple Angel Carménère, or the Montes Folly Syrah.

Montes himself has complicated feelings about Pinochet. “No one likes a dictatorship,” he told me in his home in Santiago. “But if I were to say something positive – there’s not too much of it — but if there’s something positive, it’s that we had to work hard to make a better country.” And now, Chile has the best economy in South America, he went on. “And it started with Pinochet.”