For produce, the concept of seasonality is easy to understand: In the northern hemisphere, asparagus plants shoot up in spring. Strawberries ripen in early summer. Grapes are plucked from the vines in fall. Ruby red grapefruits are at their juiciest peak in winter.

But when it comes to cheese, seasonality can be a bit confusing. Most shoppers are used to finding the same cheeses at the store throughout the year. Especially with larger-production options, these cheeses usually have the same flavor and texture as the last time they were purchased.

But for makers of artisanal cheese, seasonal differences can be significant. “We are a grass-based dairy,” says Kat Feete, cheesemaker at Meadow Creek Dairy in Galax, Va. “Grass is seasonal, so we’re seasonal.”

Since the early 2000s, Meadow Creek has been making Grayson, its best-known cheese, which has noticeable flavor variations throughout the year. “At the beginning, people didn’t understand why they couldn’t have this cheese all the time,” Feete says. “We had to explain that this is natural. This is the way that the grass works, so this is the way that we work.”

Some cheesemakers, including Andy Hatch of Uplands Cheese in Dodgeville, Wis., describe seasonal changes as a choice between complexity versus consistency. “We’re after complexity and taste of place,” Hatch says. “I think variability is just something that comes along with it, to some extent.”

Understanding the Variables

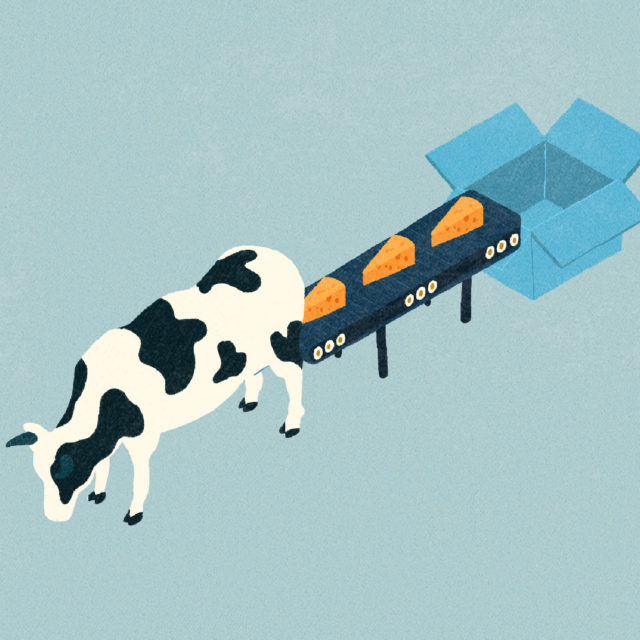

In order to understand seasonality in cheese, it’s important to first remember that cheese’s primary ingredient is milk. Cheese has been called “milk’s leap towards immortality.”

“I think fewer and fewer people understand how cheese is made,” says Kendall Russell of Lark’s Meadow Farms in Rexburg, Idaho. “I think they understand that milk is involved, but most of my customers have no understanding of the life cycle of calf, kid, and lamb being born and a lactating mother. Even less understood is the pasture component.”

The first step in making cheese is to have a female animal with a baby. Milk from that animal is only available for as long as she is lactating. For sheep, the lactation cycle lasts an average of 240 days. For goats, it’s around 284 days. For cows, it’s around 305 days.

Cheese is made from the fat and protein from milk, which has been separated from the liquid by way of fermentation. A milk’s “yield” or available fat and protein for cheesemaking will be very different depending on an animal’s diet and where she is in her lactation cycle.

Most cheese professionals agree that when milk comes from animals that have been grazed on pasture, the resulting milk and cheese have more flavor complexity. But grass does not grow year-round in most climates. So when a cheesemaker switches to another feed (such as hay or grain), the flavor of the milk will change yet again.

There is also a choice to be made between working with raw milk and pasteurized milk. Pasteurization is the heat treatment of milk to kill potentially harmful bacteria, but it also kills beneficial, flavor-driving bacteria. In the U.S., cheese aged fewer than 60 days must be pasteurized, but cheese aged for 60 days or more can be made with raw milk. Raw milk cheese will express more seasonal flavors and is generally more complex, though the milk must be handled more carefully by the cheesemaker during the production process.

Much in the way a wine bottled from a single vineyard shows distinctive character, so, too, does a cheese made from a single herd (rather than purchasing milk from several farms and pooling it). When cheesemakers choose to work with the milk from their own herds, the industry term is “farmstead cheesemaking.” Meadow Creek Dairy, Uplands Cheese, and Lark’s Meadow Farm are all farmstead, raw milk cheesemakers on top of being pasture-based.

Prioritizing Flavor Complexity

Historically, all cheese was seasonal and made with raw milk until pasteurization was invented in the late 1800s. Consumers understood and expected seasonal variations in cheese.

Today, there are ways to make more standardized, consistently available cheese. A cheesemaker can feed their animals a standardized, purchased “ration,” which includes hay, grains, vitamins, and protein-heavy crops like soybeans. They can put their animals on staggered calving intervals, pasteurize their milk, and add or subtract fat or protein.

That type of cheese is more uniform in flavor, says Carlos Yescas, program director at Oldways Cheese Coalition. “It can be made all year without regard for the weather, the feed, or the lactation cycle of the animals.” But, says Yescas, “I think when you start caring about real traditional cheeses, it becomes obvious that you want seasonal products that account for all these things.”

There are also benefits to seasonal cheesemaking beyond the flavor. “Farming can be pretty soul-draining,” says Feete. “When it’s 365 days a year and you have to milk your cows two times a day, no matter what. Having those two to three months off in the fall is great for us.”

At Uplands Cheese, Hatch makes two cheeses a year. Pleasant Ridge Reserve is produced in summer, when his cows graze on pasture; Rush Creek Reserveis is made in the fall when his cows are eating hay. Because the milk can be so variable, the recipe for these cheeses can change on even a daily basis.

“There may come a day where we grow Uplands and do a mid-size cheese company, buying outside pasteurized milk,” Hatch says. “I don’t have philosophical objections to that. But, when you’re as small and particular as we are, we need to do something different.”

Russell’s cheesemaking approach at Lark’s Meadow Farm is a bit different. To account for the variation in the milk from his flock of sheep, he makes around 30 different cheeses, all of which are tiny production and hyper-seasonal. Many are available for only a month or so. Most of his sales are at the farmers’ market in Jackson Hole, Wyo., though a few of his more consistently available cheeses can be purchased online from Caputo’s Market.

“It keeps the curiosity and the excitement high,” Russell says. “It’s not the same booth every time our customers come by.”

Conveying Terroir in Cheese

Unlike industrial cheesemakers, farmstead cheesemakers look to connect their specific land and animal herd to the character of the product. These cheeses convey terroir in a way that can’t be replicated elsewhere.

“Our goal as a farm and cheesemakers,” explains Hatch, “is to make cheese that tastes like our farm. That is also our business strategy. We are never going to compete on low-cost production or marketing budgets, so rather than make a generic product, we want to make something that is unique and couldn’t be made by other people or land or animals.”

These cheeses, like most other responsibly made products, cost more than the industrial versions. There’s no avoiding that. But, for those who can afford to spend a bit more on cheese, these cheeses are worth it.

Farmstead cheeses may be more expensive than industrial versions, but they are more sustainable in the long run. They support “local rural economies that are important to build a more sustainable agricultural system,” Yescas says.

Lark’s Meadow Farm’s Russell tells his customers: “Your cheese started with rain, sunshine, grass, and the backs of our animals. My hands have been part of it, from start to finish.”