When it comes to making beer, there are certain “off-flavor” compounds that can slip into the suds at various stages, whether from oxidation, lingering bacteria in the brewing equipment, or the use of unstable yeast strains. There’s diacetyl, which imparts a full-fledged movie-theater, buttered-popcorn flavor to beer. There’s acetaldehyde, with notes that have been likened to green apples. And there’s dimethyl sulfide, which gives off a strong vegetal, corn-like taste. Any one of these can be a nuisance, but most brewers are wise to them and have learned tried-and-true processes to keep them out of their products.

But not all off-flavors are created equal. Some are more subtle, perhaps less offensive to the common palate, and even shrugged off when noticed, thus leading to their prevalence in certain beer styles. One such culprit is tetrahydropyridine, or THP.

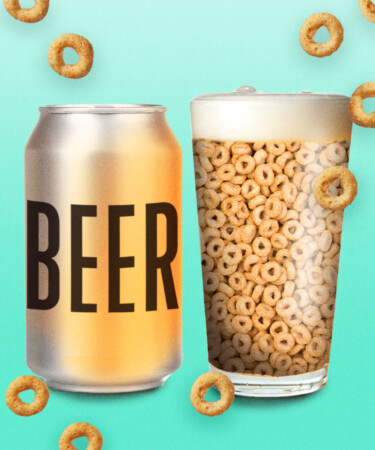

THP is often described as having a Cheerio- or “biscuit-like” flavor and can even come across as “mousy” or “urine-esque” in larger quantities. And although a lot of people love Cheerios, THP is not a desirable flavor from a brewer’s standpoint. “It’s never really adding,” says Blake Tyers, former cellar manager and now “Senior Director of Curiosity” at Georgia’s Creature Comforts Brewing Co. “If you’re in a theater and there’s a baby crying, sure, you can get used to it, but you don’t want it to be there.”

It’s worth noting that THP only shows up in sour mixed-culture beers, or beers containing Brettanomyces and lactic acid-producing-bacteria (usually Lactobacillus or Pediococcus), so IPAs, lagers, stouts, and the like aren’t susceptible to this off-flavor. Most mixed-culture brews fall under the umbrella of farmhouse- style ales, wild ales, and lambics. How THP finds its way into these beers, however, remains unknown.

As craft beer blossomed in the States, THP became more prevalent. And now, it carries on in natural wine, particularly due to the style’s use of Brettanomyces. The little research that has been done on THP is a 1995 study from Australia that explored its presence in certain wines. While researchers were able to detect the isolated compound, they couldn’t pinpoint its source.

What we do know is that THP only appears in beer and wine once they’ve been put into bottles or cans, a process that exposes the liquid to oxygen, even if only for a moment. When Creature Comforts Brewing Co. upgraded its manual, pneumatic bottle capping system to a more modern version that performs a double-vacuum purge, it went from exposing its mixed-culture beers to “all the oxygen in the world, to next to nothing.” With this upgrade, brewers were able to cut the standard bottle conditioning period from 6–8 months down to just two weeks before THP would seemingly vanish. So one thing’s for sure: Oxygen exposure plays a major role in the compound’s development.

The good news is that THP is easy to eliminate, and that’s perhaps why research has been so limited. If it’s not much of a problem, why invest time and money into solving it? Regardless, the sure-fire way to get rid of it is through bottle conditioning. After a wine, or a mixed-culture beer, is packaged, it goes through its secondary round of fermentation. During this stage, THP somehow metabolizes out of the liquid. Tyers’ best guess is that it gets broken down by Brettanomyces over time. “I compare Brett to a goat,” he says. “It will eat just about anything and everything in front of it — even things it’s not supposed to. Once all the desirable sugars are gone, then other things will be consumed, presumably including THP, which I would guess is a protein of some sort.”

A common mistake that brewers make when it comes to THP is prematurely releasing a “half-baked” beer containing the off-flavor in the hopes that consumers won’t notice. So the presence of THP is not a testament to a brewer’s skill, but to their patience. “If there’s any question of THP, it’s always best to let it sit,” says John Aravich, brewer at Source Brewing in New Jersey. “Give the beers the time they need. THP will always go away.” The same rule applies to wine.

Aravich also stresses that the compound isn’t easy to detect. It’s almost always absent in a beverage’s aroma and only noticed as a lingering aftertaste. Since the pH levels of beer and wine are lower than that of human saliva, THP only reveals itself once it enters the mouth, a more alkaline environment. There’s not a huge range in saliva pH levels; they vary between 6.2 and 7.6, but this discrepancy is enough that about 30 percent of people can’t even taste THP. It’s not a matter of one person being a more gifted somm or cicerone than the next — it comes down to genetics.

From a consumer standpoint, most won’t have to worry about THP unless buying multiple units of a specific wine or mixed-culture beer. If that first sip has a Cheerio-like flavor on the back end, let the rest of those bottles or cans sit in the fridge or cellar for a few months before revisiting them. That “biscuit” note will dissipate with time, and your palate will thank you.