At the start of the 16th century, spurred by the invention of the printing press and a push for overseas exploration, wood had become a critical part of everyday European life. It was used to construct homes and buildings, as fuel for heating and glassmaking, and it was the primary raw material for building ships. But by mid-century, Europe faced a serious wood shortage that would change the course of history. Yet despite its terrible cost, the shortage had an ironic silver lining: the birth of the Champagne bottle.

The origin of sparkling wine itself is a tangled web, most of it considered apocryphal or disputed at best. Perhaps the most famous creation myth is attributed to Dom Pérignon, the 17th-century Benedictine monk, winemaker, and cellar master of the Abbey of Hautvillers, whose alleged discovery of secondary fermentation in the bottle led him to proclaim, “Come quickly, I am tasting the stars!”

Others assert that the technique of secondary fermentation, now popularly known as méthode traditionelle and associated with Champagne production, was stolen by Pérignon from winemakers in southern France. While likely a tall tale, the southern commune Limoux claims to have created sparkling wine in 1531, predating Champagne production by an entire century. Despite his controversial role, famed Champagne house Moët & Chandon still tends a statue of Dom Pérignon on its grounds.

While these famous tales and the ubiquity of Champagne have buttressed France’s claim to sparkling wine, one of the most intriguing origin stories comes from an unexpected source. In England, a royal decree led to amazing innovations in glassware that allowed for the creation of bottles capable of withstanding the rigors of carbonation, and may have helped propel the creation of Champagne itself.

In 1615, King James I issued a proclamation prohibiting the widespread use of wood in hopes of preserving forests and keeping the Royal Navy afloat. While the wood shortage would impact all of Europe, it affected Britain first. Economic historian John U. Nef suggests that Britain’s rapidly expanding population was to blame for the shortage there. As Nef wrote in a 1977 article for Scientific American, “The population of England and Wales, about three million in the early 1530s, had nearly doubled by the 1690s.”

In a report by the BBC, Nick Higham writes, “Early modern glassmakers used charcoal made from oaks to heat their furnaces, but the navy banned the use of oak for anything other than shipbuilding.” Working around the new restrictions, England’s glassmakers resorted to coal. In an invention born of necessity, they discovered that coal’s ability to burn at higher temperatures produced stronger glass. The newfound technique produced thick, sturdy vessels — ones in which the pressure from carbon dioxide could safely be contained. It was the red-hot dawn of the Champagne bottle.

“While European counterparts were still using wood, the Champagne bottle as we know it was born in the furnaces of England,” Jai Ubhi writes in a 2019 Atlas Obscura article. He continues, “Not only did these new bottles help spawn an embryonic wine industry, but they became status objects, themselves.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this theory is disputed by the French. Pierre-Emmanuel Taittinger, of the famed Taittinger Champagne house, believes the English stumbled upon sparkling wine by accident. As Taittinger tells it, the English discovered carbonation only after leaving still wines shipped from French monks in the cold causing the wines to undergo a second fermentation.

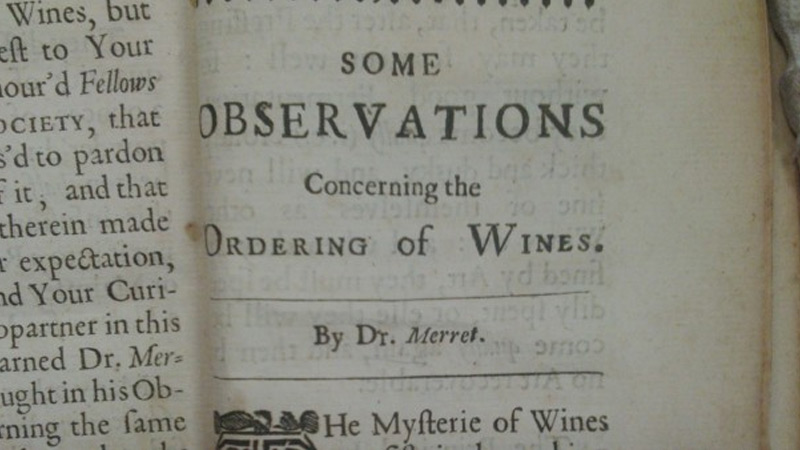

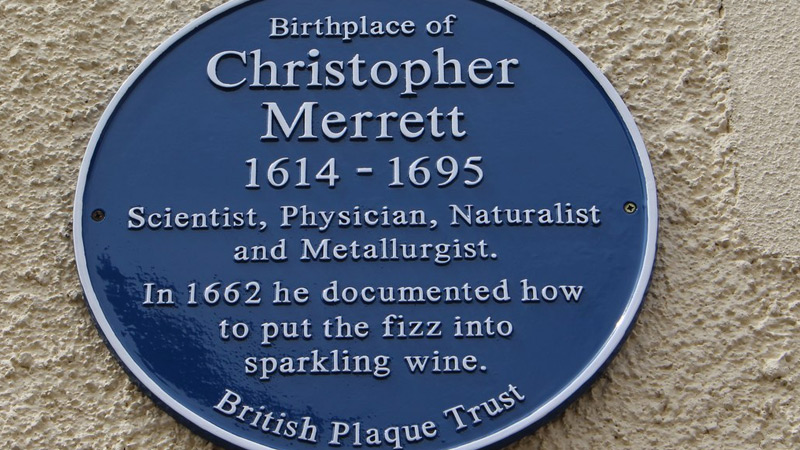

Not to be outdone, others point to the writings of scientist and Englishman Christopher Merrett who, in a 1662 report, wrote the first known account of a manufacture of sparkling wine. As Atlas Obscura points out, “Sir Christopher Merrett’s paper on the secondary fermentation of wine was submitted to the Royal Academy in 1663,” several years before Dom P’s “discovery.”

Merrett’s narrative appeared prior to any known French accounts, leading many to wonder whether he really was sparkling wine’s rightful inventor. In 2017, a plaque was put up in the town of Winchcombe, England, paying tribute to Merrett for “documenting how to put the fizz into sparkling wine.”

No matter who invented sparkling wine, the ship-building supply shortage and glassmaking innovations of England’s working class undoubtedly helped spark the still-burning flame of Champagne, igniting the proliferation of a beloved cultural delicacy around the world.